For the month of August we are revisiting some of our favorite content from the past year. Publication of new work will resume on September 1.

“I believe New Yorkers. Whether they’ve ever questioned the dream in which they live, I wouldn’t know, because I won’t ever dare ask that question.”

– Dylan Thomas

In my first months in New York City I rode in the back of taxicabs through Central Park thinking, “When will this sink in? When will it feel like I know where I am.” I didn’t think I was dreaming – rather, I felt the whole city was dreaming with me inside of it, a poppy-field illusion, a drug trip induced by hidden valves releasing an experimental hallucinogen. The city needed to pinch itself awake, collectively, and climb out of the hollow to find out what was really going on.

“I stopped at Lexington Avenue,” wrote Joan Didion of her arrival in the city, “and bought a peach and stood on the corner eating it and knew that I had come out of the West and reached the mirage.” You arrive, you reach the mirage, and you wait for it to clear.

It’s taken me four years to feel like I’m capable of articulating thoughts about New York. I arrived here in 2010 on the Upper West Side of Manhattan – a Craigslist apartment hunt gone wrong, because I was naïve to the terrors of that part of the city. I’d searched from my basement flat in Wellington, New Zealand, and all the Upper West Side had conjured in my mind at that time was trees. The rent was expensive, but I had a partner to share it with and the location was close to where I would be attending graduate school. I’d hoped the Upper West was more diverse, and slightly wilder than the Upper East Side, which conjured Sex and the City and Gossip Girl and held the abstract term “Madison Avenue” in its manicured hand, all of which horrified me, because I thought I might become fake and hollow if I lived there. I was earthy. I’d grown up in the Kiwi bush. I’d traveled the world as an adult, but I’d stayed true to my down-to-earth values. I thought politeness had inherent value.

In a move that was the opposite to Ruth Curry’s in her essay “Out of Season” (collected in Goodbye to All That, essays by writers who left New York), I flew from a “city” of 150,000 to a City of eight million. I flew from southern hemisphere to northern, from autumn to spring. I flew from a quiet, polite culture of “bottomless reserve,” to a culture of individuals desiring to stand out, a people characterized by assertiveness bordering on aggression. I stumbled around Manhattan that first summer learning basic survival skills, like how to avoid being crushed by throngs of pedestrians and ruthless drivers, and how to avoid eating at restaurants that would give you Delhi Belly to rival India’s. I watched a huge cockroach skittle towards my hand on a bar top in the Lower East Side, and I saw rats outside my house relay items of trash to one another like a military unit.

I learned to ignore the insults that were passed casually around the streets of the Upper West, the “Watch It, Would Ya!” and the sarcastic “thank you!” that emitted more readily than even my classic New Zealand “Oh! Excuse me.” I encountered an outright refusal, sometimes, for people to serve me in stores because “they couldn’t understand my accent.” There where often blank stares when I spoke, or a continual, single phrase fired at me over and over: Where Are You From. This was followed by an obvious appraisal of my dress, my fitness, my (lack of) makeup, to determine how much money I ‘really’ had (they usually got it right: very little. What was I doing there?). I wasn’t sure if I’d come to a place that was incredibly amazing, or hugely awful. To some extent, I wasn’t sure if I’d arrived somewhere real at all.

Because New York is a place that’s intrinsically unbelievable. Life clings on by a graying hairbreadth. People live inside subway tunnels, I soon discovered, and eat garbage out of trash cans. People live in buildings that sometimes go without heating in single digit temperatures. Many people work every day of the week, and have no medical insurance, can’t afford dental work, and still spend evenings “being creative,” working on their start-up app that has the power to streamline collective decision-making, or their socio-political gaming spaces, or their movement building spaces. Perhaps they’re of the old guard and they work late nights on their screenplays, their installations, their angst-ridden novels (“practically everybody in New York has half a mind to write a book – and does,” said Groucho Marx). Either way, many people spend very long hours talking about doing these things. There’s an impression that everyone is plotting, is in action, all of the time, simultaneously surviving and simultaneously focused on dreams of the future.

“I think of creative life in NYC as playing a game,” says sculptor and photographer Robyn Renee Hasty, “the advice anyone will give you is ‘fake it til you make it,’ which seems to mean look the part until the appearance becomes reality.” Hasty migrated to the city from Florida when she was seventeen, and considers her ‘formative years’ were spent here. She is now an artist-in-residence at Pioneer Works – a stunning, multimillion-dollar arts center in Red Hook – and creates elaborate environmental art with Swoon. She was recently featured in the New York Times for her stencil artwork. But she still worries constantly about finances, and feels little security. “To play the game you have to look and act the part, and play by the rules. If you really really want something, or worse desperately need it, the best thing to do is play like you don’t care.”

Three years after my Manhattan awakening on the Upper West Side – which my partner and I had left fairly quickly for a calmer place further uptown – I found myself “qualified” as a writer with an MFA in hand. I was also worse than broke – in debt, and single again. My long-term relationship had not survived the game playing of the city. I had attained what I’d come here for, in a sense – the establishment of my desire to live as a writer, in a place big and diverse enough to allow a full spectrum of creativity – but I had lost a lot in exchange for that: a secure partnership and my down-to-earth values, including my valued Kiwi politeness.

Still, I had no will to leave. I disagreed with so much of what I thought the city stood for, but within its chaos I had found a community and networks of people that truly, for the first time I felt, really got who I was. Writers and artists too, they understood the sort of daily self-questioning that choosing a life like this entailed, the potential for endlessly empty bank accounts and a lack of respect from more traditionally productive people. We got one another, even if they had trouble understanding my accent when I said the most elementary words like “art”and “water.”

We are drawn together, in part, because we’re determined to see the city’s seduction play out in full. The city attracts stubbornness, the sort of person who refuses to give up when any rational person would. Maybe – as writer Justin Taylor recently said – it’s that “the city attracts people with a high tolerance for suffering.” New York is for the very young and the very rich, as Didion famously wrote, and it is for the daring and desperate too. It’s for those who are reckless or brave enough to take huge risks, who can stand to play the game.

It’s also for those who seek the mental challenge of participating in making the mirage they seek. In answer to Dylan Thomas’ unasked question, I believe lots of New Yorkers know they are living in a carefully manifested image of a city, a projection on top of the real thing. The “New York” that transplants seek, and capitalist culture promotes, is a sparkly, gold-threaded place, mapped on top of a grimy, grinding New York that exploits many of the people who make it tick.

The economic and social networks of the city openly acknowledge the pivotal roll of image in the construction of this city’s power. Gym advertisements in the financial distract even proclaim that “your image is your most important asset.” Driving down the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway an overhead sign marks the borough border. “Welcome to Brooklyn: Believe the hype!” The banner is signed by Mayor Bill de Blasio. Not only are city officials aware of the power of hype, they know New Yorkers are smart enough to see it for what it is. How do you effectively advertise to a city of advertising executives and copywriters?

The wry tone carries through to other city department slogans, with lesser or greater effect, depending on the level of wit of the communications team. The city’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, whose name pays testament to the archaism that infiltrates it, always fumbles in its messaging. “At age 80, who doesn’t need a facelift?” asks one of its subway ads. The ad alludes to the necessary refurbishment of a station, proving that somewhere, somehow, they are doing something – but also, the copy doesn’t quite get it right. At age 80? A facelift? Even Upper East Siders wouldn’t go that far. At age 60, or 70 maybe. 80 feels a bit depraved. The MTA tries to get in on NYC’s image-centric culture and fails, a bit like a foreigner making a joke with an accent that people can’t quite understand.

Is it worthwhile to invest so much energy in perfecting your physical appearance, advancing your career, expanding creatively, and, perhaps the most challenging of all, developing your personal relationships? As we engage in the massive labor of self-perfection, so too do we work to make perfect the image of the place we live in – the city, after all, is a reflection of ourselves. But it remains forever outside of our grasp. “The city is an abstraction,” says Justin Taylor. “One of the great things about the city is that it doesn’t care. I think that’s very much to its credit.”

Joan Didion “reached the mirage” when she was twenty-two or twenty-three, and “knew that it would cost something sooner or later.” What she and perhaps Dylan Thomas were tapping into was the fallibility of the image. Thomas was concerned that by asking New Yorkers about their mirage, he might pop it like an all too delicate ego. Didion, I believe was seeing that the mirage New Yorkers were constructing would ultimately serve its own interests first.

Four years here have helped me to start to feel at last where I am. This grounding has come, paradoxically, from an increasing awareness of the mirage in which I participate, the mirage I actively create by living here. I term myself a ‘writer’ yet I spend more time trying to find the means to provide myself time and space to write than I spend writing. I earn more money doing things I don’t want to be doing – editing college entrance essays, drafting grant applications, babysitting overindulged cats – than I do selling writing. But as the mirage clears, my community networks stick around, like cobwebs after rain. As I learn to survive on my own, my full capacities are tested. My love for the messy reality of this place expands.

“A hundred times,” says Le Corbusier, “I have thought New York is a catastrophe, and fifty times: it is a beautiful catastrophe.” Beautiful catastrophes are a rare thing, and perhaps worth twice as much as a plain catastrophe. That’s New York – an irrational mess, threaded with gold – so hard to look away from.

Melody Nixon, a New Zealand-born writer living in New York City, is the Interviews Editor for The Common.

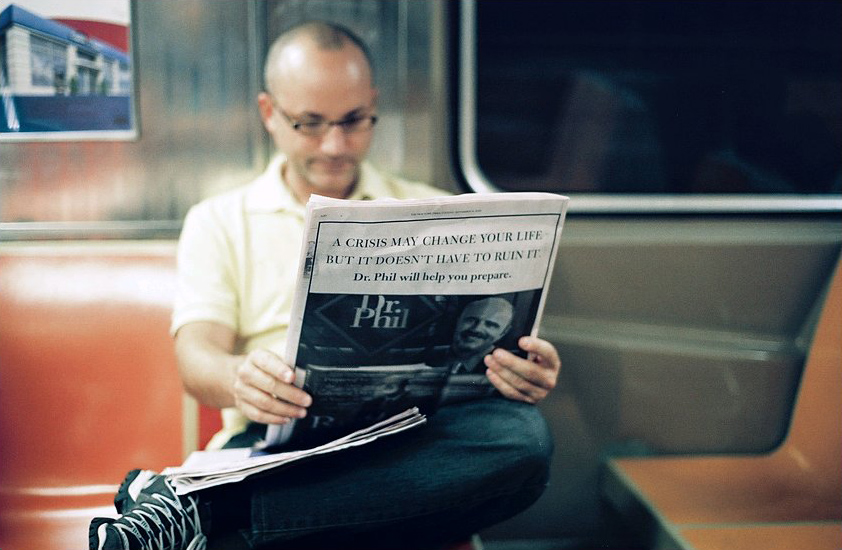

Photos by author.