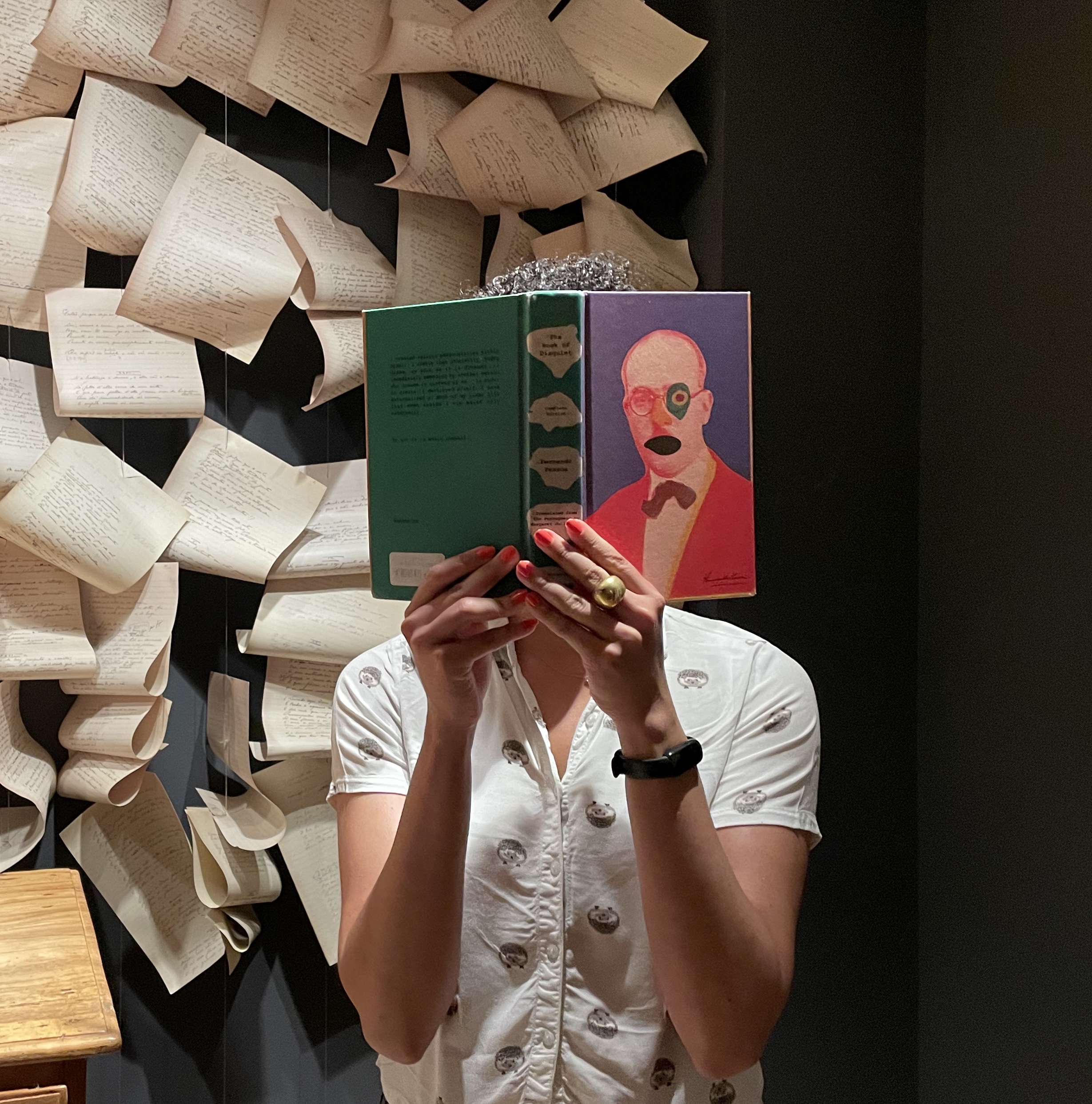

These piece is excerpted from a memoir-cookbook entitled Group Living and Other Recipes by Lola Milholland ’07, a guest at Amherst College’s LitFest 2025. Register for this exciting, 10th-anniversary celebration of Amherst’s literary legacy and life.

When I visit my mom in the Driftless region of southwest Wisconsin, we bike together. She’ll pull out the old road bike her brother Paul built from parts when he lived with us in Portland. It’s in the shed that sits between her little year-round greenhouse and the outhouse that serves as the only loo on the property. We cycle up her one-mile gravel driveway, out to roads that twist and turn through hilly farmland, past Amish kids in overalls and sturdy full-length dresses working with horses and hanging up laundry. From the ridgetops, the hills in every direction look like bubbles on pizza dough.

In the fall, the hillsides change color every day. The basswood leaves turn a daisy yellow, and the oak leaves become the orange-red of a Firecracker ice pop. The Amish on Wolf Valley Road will be harvesting corn. Their two-horse team pulls a metal scythe through the stalks, leaving behind a flat field of roughage like a pile of cut hair.

My mom sets her bike seat high—she claims it keeps her left foot from cramping. As she pedals, her butt swishes across the saddle, side to side, so she can reach each pedal at its lowest point. I bike a little ways behind and watch her whole body swinging left, right, left, right, like a pendulum. The Amish in their fields and buggies wave at us.

What I love most about biking with my mom is watching her fly downhill. She’s now in her seventies and still loves to go fast. She dresses like a hard-core cyclist: ass-tight shiny black shorts, gloves, clip-in sandals, a fanny pack slung on her left hip that I know has a half-smoked joint in it. Hay Valley Road descends steeply from the get-go. I watch her speed up, stand on her pedals like a jockey, and lean into the wind.

“Hoohooooo!” she calls out, like an owl.

“Hoohooooo!” I reply.

I imprint this image of my mom in my memory: leading the way, a bit stoned and giddy, speeding down a road toward the Kickapoo River as fast as she can.

_______________

When I was nine, perched tentatively between my inner world and the whale mouth of pop culture, my mom started freelancing for a dairy cooperative, Organic Valley. After a while, they hired her as marketing director, and for the next nine years, she traveled from Portland to their headquarters in southwest Wisconsin for part of every month. For the first few years, she stayed in a plywood one-room cabin called the Belvie (or Belvedere), which was an outbuilding of a larger house called the Kettle Lodge.

An old man named Jerome—who remained forever old and, therefore, mysteriously eternal—lived in the Kettle Lodge at that time. Jerome looked like a wizened goat god, an ancient mischievous Pan. He was without an inch of fat, his skin stretched over small muscles, his cheeks hollow beneath round cheekbones, many of his teeth missing, his beard long, white, and fluffy, like mohair. He was shoeless, always. In the summer, he was shirtless and wore tiny swim trunks. His ribcage protruded beneath his skin like the prow of a little boat. I could often see his testicles hanging out of one side of his shorts. This didn’t shock me—I was familiar with saggy testicles from nude beaches and hot springs, the little ETs men kept hidden in their pants that would loll out on hot days. My mom told me Jerome had suffered from polio as a child, although I didn’t have any idea what that meant.

Jerome was the most engrossing conversationalist I’d ever met. I’d carefully choose when to start a conversation with him because even when I was age ten or twelve or fourteen we’d end up talking for hours. He treated me like I was fascinating and wise. His conversations had a rhythm—his inquiry, my reply, his response, my reply, a new inquiry—that felt like a train you couldn’t disembark from. His voice also had a rhythmic rise and fall.

“Tell me, Lola, what do you think about China’s Five-Year Plans?”

Because I was a try-hard, I’d make up answers to hear him reply and expound. A former high-level accountant at Sinclair Oil, Jerome had dropped out of corporate life and, in 1974, found himself in the Driftless region of Wisconsin. He helped build the Kettle, honed his astrology and numerology practices, and made a living as a canny tax accountant. “I like that number,” he’d say, his voice rolling, as he talked clients through their worksheets.

Jerome’s reclusive brother, Mick, lived in another outbuilding and appeared very occasionally—maybe once a week—with the suddenness of remembering a forgotten word. Mick! Mick was also agelessly old, with stringy white hair and deep-set eyes. He wrote in his books, over the printed words, in red and blue ink so that you couldn’t read what was beneath—all meaning was hoarded and erased. He was always kind to me, mumbling questions and leaving without the answers, which I was glad not to give. My mom told me that it wasn’t too many drugs or Vietnam that had led to Mick’s hermetic lifestyle but something in his nature.

When I visited in the summers as a kid, their mom, Geneva, would also be staying there. I could hardly believe that these biblical old men had a sweet, loving mother who was even older than they were, who made fruit salads and devotedly tended her flower beds. Other people lived at the Kettle too, sometimes for years, but the overall social makeup of the community felt transitory.

Excerpted from Group Living and Other Recipes © 2024 by Lola Milholland. Published with permission of Spiegel & Grau.

Lola Milholland ’07 is a food-business owner and writer whose work has appeared in The Guardian, Time, Oprah Daily and elsewhere. A former editor for Edible Portland magazine, she currently lives in Portland, OR., and runs Umi Organic, a noodle company with a commitment to providing nutritious public-school lunch. Her debut book, Group Living and Other Recipes: A Memoir, was published in 2024.