Review by HANNAH GERSEN

Movie directed by AMALIA ULMAN

In Amalia Ulman’s debut feature, El Planeta, which she wrote and directed, Ulman and her real-life mother (Ale Ulman) play a mother and a daughter awaiting eviction. Ulman’s character, Leo (short for Leonor), has returned home after the death of her father, whose sporadic alimony payments barely supported her mother when he was alive. Leo is jobless and so is her mother, María. The two women spend most of the film in their narrow galley kitchen where the sunlight is abundant, and they aren’t tempted to waste money on electric lighting. Their refrigerator is empty, save for the tiny slips of paper María places in the freezer, each one bearing the handwritten name of an enemy. Atop the refrigerator are multiple glasses of water, which have something to do with María’s witchcraft—a practice that seems more like a distracting hobby than a coherent belief system. Leo sews bizarre yet fashionable clothing by hand, having sold her sewing machine for cash. They drink coffee, cook pasta, and, when they are really hungry, dress up in designer clothing and run up large bills in restaurants and stores, promising to pay later or claiming that Leo’s boyfriend is a local politician who will pick up the tab. They live in Gijón, a small city on Spain’s northern coast, a place hit hard by the global recession, with shuttered shops and empty tourist districts. It’s no wonder these two women are more at home in their delusions of grandeur.

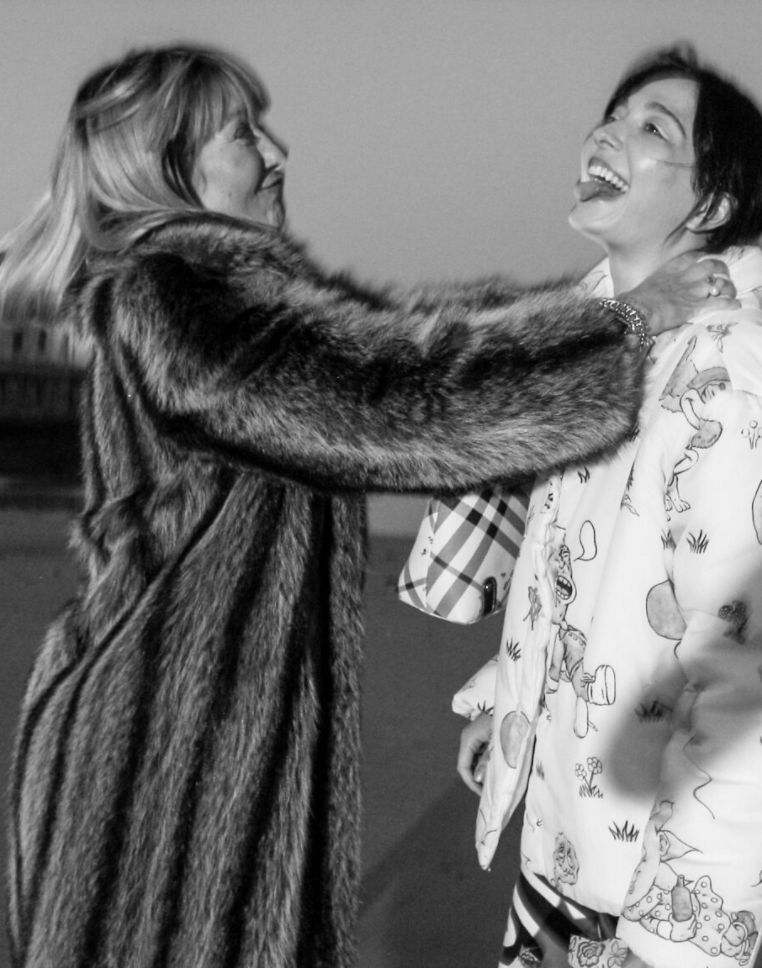

Although Ulman was inspired by a news story about a pair of mother-daughter grifters, Justina and Ana Belén, El Planeta doesn’t have the usual satirical or moralistic tone of a based-on-a-true-life story. Instead, the mood is one of resigned wistfulness. And as far as scam artists go, Leo and her mother aren’t very ambitious; they aren’t going for a big con, they just want to live like they always have. They seem emotionally stuck in the past; one of their favorite topics of conversation is their love of their deceased cat. There’s something childish about their passivity, and their love of glamour seems more like a way of nurturing their fantasies of middle-class security than trying to convince strangers they’ll be able to pay the debts they’re ringing up. In a telling moment, María attempts to wear her fur coat the moment it’s a tiny bit chilly, and is disappointed when she realizes it’s still too hot—her impractical nature apparent both in her desire to wear the jacket on a warm day and her insistence on clinging to it when she could easily sell it.

Of the two women, Leo is the more sympathetic, and I was surprised to read in an interview that Ulman considered Leo’s character to be more unlikeable. She’s unlikeable only if you think it’s silly to be young and to want interesting work, romance, and fun. While it’s true that Leo isn’t looking very hard to find work to support herself, it’s clear that Gijón is a sleepy town, without many jobs on offer. In an early scene that plays as comic, Leo meets up with a man to arrange what seems to be a sugar baby gig, but when she finds out how little she’ll be paid for sex work, she demurs. Undeterred, the man tells her to think about it, excusing himself to pick up his daughters from ballet class—a funny moment that shows there’s a middle-class life happening somewhere in Gijón. Later, when Leo interviews for a freelance stylist gig that matches her artistic skill set, she’s dismayed to learn that she will not be paid well or even provided with travel expenses. Instead, she’s supposed to benefit from the “exposure” she’ll get for working on a prestigious project. What goes unsaid is that “paying” via exposure is not only a way to get cheap labor but of hiring people who already have a certain income. Unfortunately for Leo, it’s a kind of class privilege that can’t be faked with good lighting and white lies.

Ulman comes to film from the art world, where she is a visual artist best known for Excellences and Perfections, a piece of performance art that took place on her personal Instagram account over a four-month period in 2014. Elle magazine called Ulman “the first great Instagram artist,” an accolade that might sound absurd until you look at the narrative she created on her feed, staging an extreme makeover that included a platinum dye job, fake breast augmentation, a nervous breakdown, and a period of recovery. Her Instagram followers believed the drama to be real, and even some of Ulman’s friends and colleagues fell for the ruse, because Ulman was using her own face, body, and name. Ulman composed her photographs to mimic selfie styles and captions that are popular with young women. Some of this Instagram sensibility makes its way into Ulman’s film, but in an ironic way. Instead of artfully arranged pastries, Ulman gives us a still shot of half-eaten ones. Instead of selfies, Ulman shows María posing for Leo, her image multiplied and distorted in a new filter. There’s also the simple fact that Ulman cast herself and her mother as leads, and set the movie in her hometown, lending the movie an autobiographical sheen.

Watching at home on my laptop, my first and most sustained impression of El Planeta was that it was the first thing I’d seen that looked good on a computer screen. Shot in black and white for budgetary reasons, there is a simplicity to the images that works well in a small format. (Perhaps Ulman’s work on Instagram also helped her to compose for a shrunken frame.) Her narrative is pared down, a series of episodes that lead to the inevitable: María and Leo’s exposure as small-time crooks. Both Ulmans are charismatic enough to hold your interest, but it took me a while to figure out why Ulman the director was interested in this mother-daughter duo. Her film surprises because it isn’t a character study or a crime story; instead, she seems to be looking at the gap between performance and reality as Leo and her mother pretend to be well-to-do ladies who lunch. In a revealing scene near the end of the movie, Leo overhears a conversation in a waiting room, in which a woman tells two anecdotes of people being caught in fraudulent performances. As she tells the story, the camera pans to show the celebrity magazines on display on the coffee table, and then to the other women in the waiting room who are absorbed in their phones. Leo is listening carefully, possibly because she knows that one day, she and her mother will be caught. In the scenes that follow, Leo and her mother indulge in some more petty fraud, and as you watch them wander through Gijón, dressed to the nines and pretending to have enough money for a salon visit, you wonder for whom they are keeping up appearances.

Hannah Gersen is the author of Home Field and a staff writer at The Millions. She writes about movies on her blog, thelmaandalice.com, and a monthly newsletter: https://thelmaandalice.substack.com.