A familiar sound comes from the other room. A voice—from Kentucky; from a monitor speaker, ten feet away in Massachusetts. I hear it in the kitchen. A clip of speech, a cadence heard again and for not the last time. Open floor plan living: all sounds permeate. Racket of chickens, dogs, lilting voice, banjo.

A film, incomplete—still very much its audio-visual pieces. We cohabitate, this thing and I. I am not the maker, though he lives here too. I am adjacent to the making.

I was there when it happened. The beginnings of this thing that has now sprawled through our lives. That was three years ago, on a summer road trip from Boston to points south, stopping to see friends in Charlottesville, Nashville, Memphis, before making our way back north.

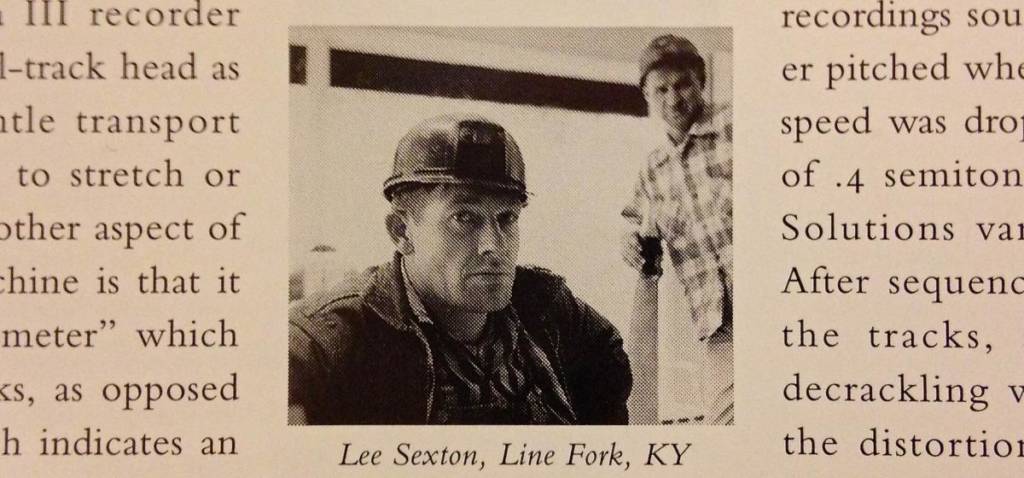

From our last stop in Maces Springs, VA, the detour to Linefork, KY, was ostensibly under two hours. With rain pouring down the mountain switchbacks we took it slow. Vic had been visiting the area off and on over the past ten or so years, making periodic trips to learn from Lee Sexton, a vital link to the iconic sound of old-time Eastern Kentucky banjo playing, with a sound all his own. He’d first heard Lee on the landmark 1960 Smithsonian Folkways recording, Mountain Music of Kentucky, and traced him here, based on a photo and caption in the CD’s liner notes.

We’d called the day before, to see if Lee was around and up for visitors. Not wanting to show up hungry, we picnicked on the grounds of the Campbell Branch School—the rain having subsided—before making our way across the narrow bridge to Lee and Opal’s place.

As Opal shelled beans, Lee recounted various stories, told the comings and goings of his banjos: this one lost, that one stolen, his very first—made from a groundhog hide, purchased for a dollar as a child with money he earned clearing a cornfield—he pulls out to show us. Vic recorded this session with Lee, so in writing this, I go back and listen again to our two hours together. We stay awhile, the rain returns, and Lee shows Vic the tunings and fingerings for “Single Girl,” “John Lewis,” “Last of Callahan.” Opal and I visit. She asks if I play any music (not really), if we have a garden (just some potted herbs on a shady porch). On those tracks from the LS11, I hear again the energy of Lee’s playing—my first encounter with it—the humor of his stories, the murmur of our voices and the rain in the background.

Afterward, driving to the Whitesburg Super 8, we marveled over those hours. How Lee and Opal welcomed us into their home. That the man is in his 80s, a retired coal-miner with black lung, still farming the land where he was born and raised, still playing square dances, and teaching banjo. How challenging it can be to learn, to teach Lee’s music to Vic’s students up in Boston. The importance and utterly unique nature of Lee’s sound—shaped by a series of hand injuries sustained in the mines and in his garden.

The next morning we headed over to Appalshop, a non-profit organization that (among other things) documents and celebrates Appalachian life and culture, to see if anyone there had recorded Lee’s playing on video, or would have interest to—something Vic had asked Lee about when we were together. In the end, it wasn’t in the cards. As we wound our way toward home over the next week, we came to the seemingly inescapable conclusion that Vic should do it himself.

That’s where Jeff came in. He and Vic are friends and collaborators from way back. Jeff’s an experienced filmmaker who was prescient enough to recognize in some preliminary footage Vic shot, that Lee and Opal’s lives, if they were willing to share them, would resonate on the screen as much as Lee’s music. That there was something there, and something to be made.

The made thing is documentary, not surveillance, but ostensibly non-fiction. Yet every decision in the making forces a reckoning with the gap between what is being made, and what is real, was true, happened. I recall Jeff describing the making of a film as a process that by its nature undeniably steps toward fiction.

It is a project inherently shaped by and grappling with distance: from here to Kentucky, from one side of the camera to the other, life to screen. Through the editing process, recorded phrases and songs from the past, from another place, become part of our lives, our home. It’s a collaboration that, with our move to Western Mass and then Jeff’s to Marseille, became long- and then longer-distance, at times seemingly untenable. As I’m cooking, reading, writing, idling, I hear their voices in the next room, delayed voices communicating through Wi-Fi, across an ocean.

The made thing, in its making, compresses moments captured over several years (the seasonal cycle of the garden, daily visits to the senior center, a night at the square dance, hours spent playing, teaching, occupied in the daily tasks and amusements of home) into not even 100 minutes. Its condensed chronology generates an artificial sense of what happened. It is a created ordering of events, of people in spaces in time. The question is not, did this happen after that? But rather, what does this do here?What is desired is not an utterly faithful rendering of what happened when, but a whole thing, the sense of a true portrait.

This thing being coaxed into being has already been several versions of itself. Success and failure in varying ratios. I was not there for the filming, but have seen and heard much of the raw material. Watched lengthy uncut shots become loosely, then tightly, held together sequences. Seen iterations of these captured moments, moving image and audio brought together, peeled apart, lined-up and reordered. Witnessed sound stripped from image. Watched moments of other peoples’ lives brought forth, emphasized, compressed, erased, and brought back again. Tested different ways of ending.

In the ordering and reordering of sequences, themes undeniably emerge, assumptions take hold. Expectations are alternately met and frustrated. Categories of content take shape, and must be compiled, distributed, handled. For a time there is not enough music, not enough Opal. For a time there is too much a sense of illness, aging. Minefields are everywhere. Narrative is desired, avoided, inescapable, inadequate. Care is required. Pacing, essential.

I sit through screenings, stop by Vic’s desk for a moment mid-editing. I make my opinions known. Maintain: this scene must stay, that should go. More music, more prelude. I argue the validity of my position. Though I am just another voice in the room. This thing is not mine, but I am a part of it. Or near to it. I feel, to a degree, culpable. And exhilarated at the form taking shape, the made thing nearing completion. Lee and Opal, Linefork, the intoxicating beauty—of the landscape, dialect, and music of a place, of other lives—brought into my space, made present for that potential future audience who will, we hope, be floored by it.

Learn more about Linefork here.

Elizabeth Witte is the Associate Editor of The Common.

Photos by Vic Rawlings