I’m no horticulturalist. I don’t have a garden. It’s renderings of flowers and plants that make me stop short and stare: a page full of small bits of white and domed yellow, the spindly green branching almost like a seaweed. A field of lines and colors on paper becomes a beautiful, vivid thing that recalls the plant I could see and touch and know, if I dared. But illustration owns its subject; as a deliberate man-made composition, it translates the natural world through mind and body, through a series of human choices and means, into an utterly new form. Nature moves from its vast, fascinating world of complex systems to another, smaller one of confinement and relocation. The illustration isolates and resituates its subject in the rectangular page, the book’s binding.

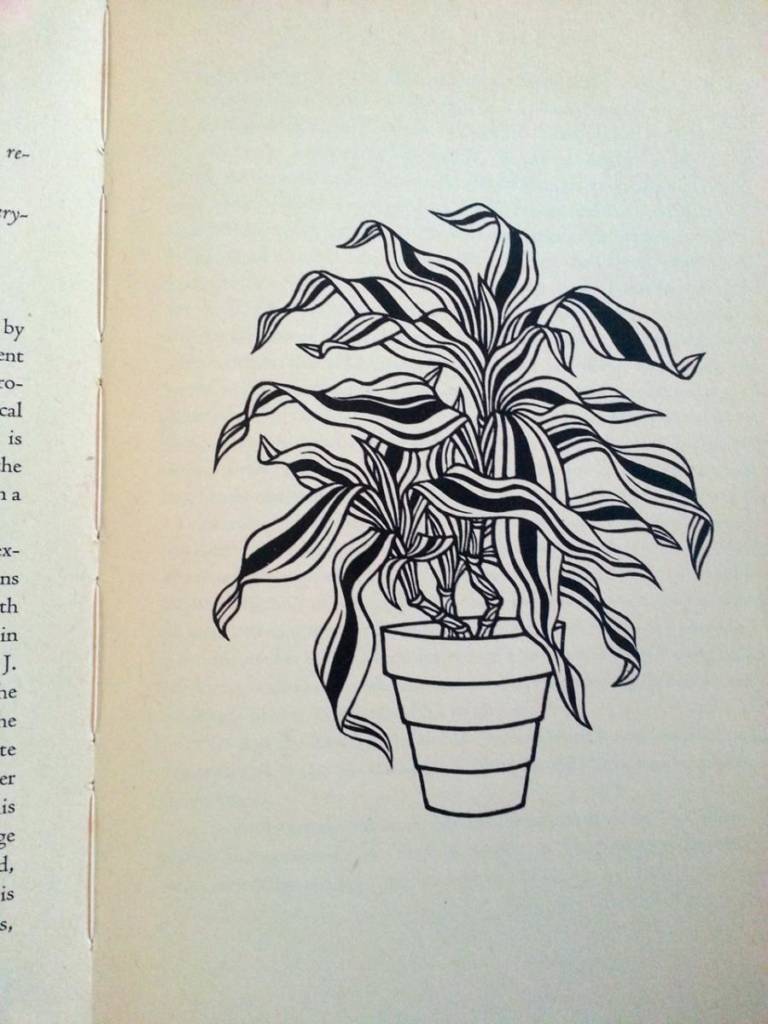

I open a book full of plant life and find in the text a depth to explore (an expedition metaphor of some sort – with the associations of goal and effort – seems appropriate). Heavy with facts and histories, the text engages in its own right, but I cannot claim knowledge as my aim. It’s seeing: e.g., the stark black and white woodcuts in Flora Exotica. The thick dark lines becoming plant and pattern made this volume mine; these images compelled me to buy the volume, to own them. Jacques Hnizdovsky’s prints pair with Gordon DeWolf’s text: floral biographies track the circuitous pathways of collection and commerce that brought each plant to European knowledge and market; the various curative properties and novel applications. I pick at the text in fits and starts but then: every few pages, the stunning binary of black line and negative space.

An illustration (especially one depicting the natural world) may compress or magnify its subject, both in terms of size and complexity. The degree of detail and wholeness must reckon with the great equalizer of available space in the given dimensions of the page. We may have complete plant forms simplified to line and pattern, or the full-color, detailed, vertical section of a flower head. There are the pocket-sized books and the coffee table tomes. The rendered plant-image is flat, cleaned up, expanded or miniaturized, idealized. There is no smell, no scent-heavy air, or sound or sweat or bugs crawling.

These sorts of images are a portal to an entirely other place. Not a native habitat, not the space I inhabit as reader and viewer. In company with their texts, these pictures inhabit a no-man’s land between science and art with all of the beauty and less weightiness. With the woodcuts described above, this place begins with the image in a vacuum of white space. Other times, there’s a presented setting and story.

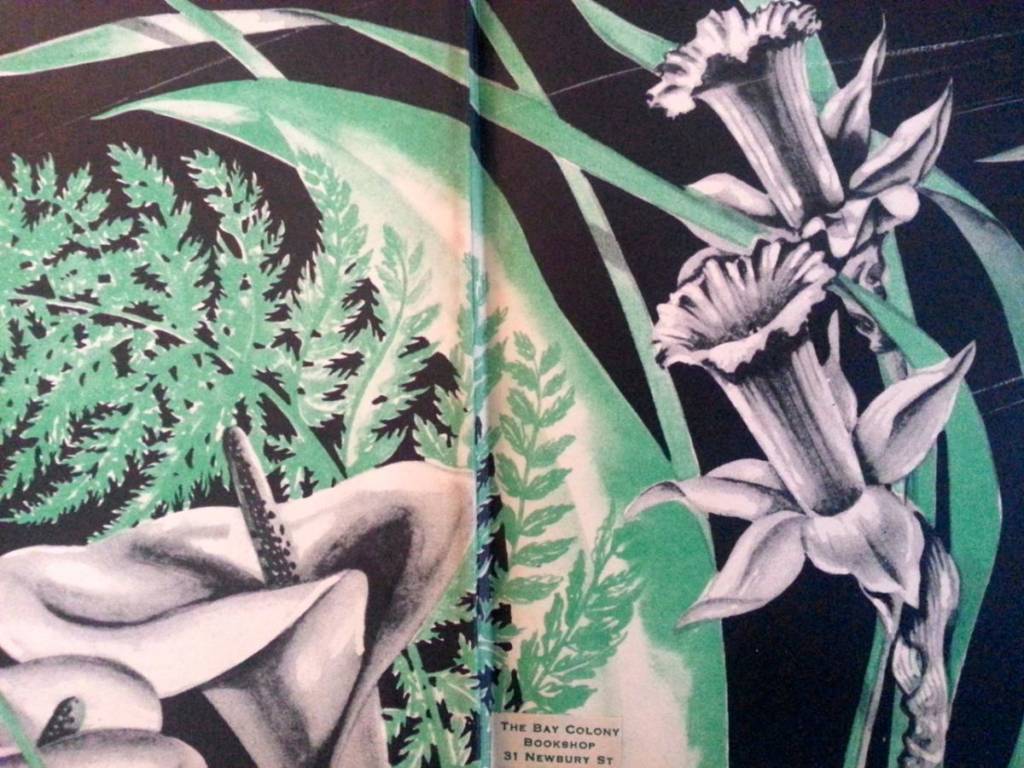

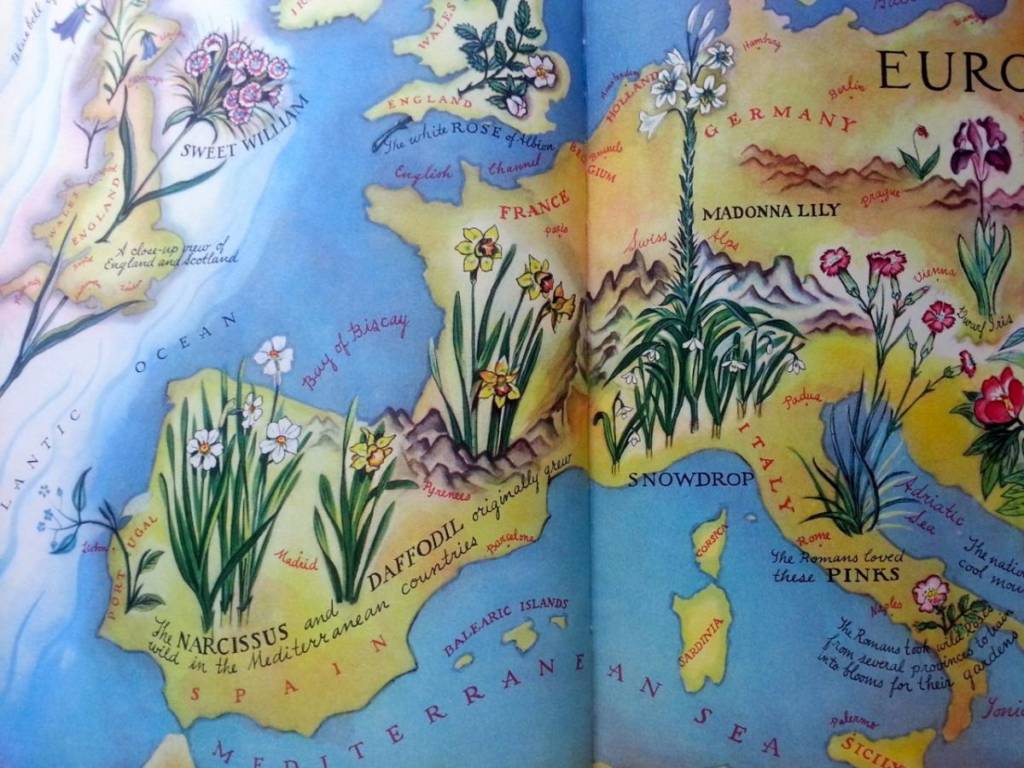

The watery floral cartography of Where Did Your Garden Grow? (illustrations by Helene Carter, words by Jannette May Lucas) maps botanical homelands. Carter maps “the four quarters of the globe” – Asia Minor, Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, Mexico, South America – all in full color, flowers towering over each land mass. I open the cover and the endpaper immediately compels my eyes to linger on the matte windswept gray-scale and green featherings, the soft black backdrop. I find myself skimming snippets—beginnings and transplantations of various garden denizens—while flipping forward and back again to each picture page. Mexico, awash in soft peach, crossed by shaky blue lines of rivers and swaths of mountains, studded with sweet spots of crimson (bell) and blue (bonnet), an outstretched dahlia proud and grand, each sweetly labeled.

As a child I paged through Ruth Heller’s flora and fauna series, particularly Plants That Never Ever Bloom (see also: The Reason for a Flower, Animals Born Alive and Well, and Chickens Aren’t the Only Ones). Heller’s saturated dreamscapes of ferns, mushrooms, lichen, algae have remained in my mind all these years as an image-undercurrent, those sorts of pictures you can return to with little provocation and almost unsettling clarity. I recently reclaimed these books from my parents’ basement and felt the relief that comes with a) getting one’s hands on some long-absent, semi-lost thing, and b) the material satisfaction and validation of confirming an oft-recalled childhood memory. The images are as stunning as I’d remembered. Each semi-glossy page, each spread of lines renders worlds I long(ed) to enter.

As a means of thinking and seeing more or differently, these sorts of illustrated books offer also a means to freely enjoy beauty without subtext. The text is there, but I’m with each image in isolation, a small sample brought to me through the artist’s eye and hand. Between my hands I have the illustration proper (a direct connection). There’s a privacy to the experience; it’s entirely separate from that informative space of the text, is distinct from the original, ‘real’ subject. With the plant in nature I’d be one among countless organisms; on paper a sense of intimacy prevails.

Sure, you could say such nature-on-the-page renderings are mere proxies, mediated experiences of the original, that the real plant kingdom should garner my gawking. And while issues of representation and replication (of the plant as image, of the image in each copy of the book) are very much at play, I don’t intend here a treatise on the nature of image and symbol in contemporary society. In this particular experience of looking and seeing, another sort of knowing and understanding comes into play, one beyond the world of utility, taxonomy, and analysis. Seeing is not, here, a part of a goal-oriented process. A sharp focus on the achievement of knowing, of being able to point and say, “I can name that,” becomes tiresome. Here, seeing is a simple, but rich, wonder: no bragging rights earned, just a moment of something beautiful.

Elizabeth Witte received her MFA in poetry from the Bennington Writing Seminars and is Assistant Editor of The Common.

Photos by author