ZINZI CLEMMONS interviews MARIE-HELENE BERTINO

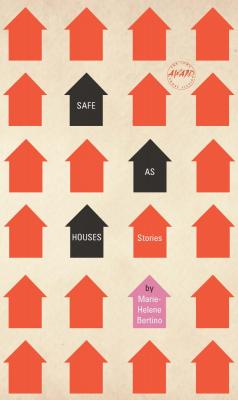

Marie-Helene Bertino published her debut collection of short stories, Safe As Houses, in 2012. It won the Iowa Short Fiction Award, and was long listed for the Story Prize, and for The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. She hails from Philadelphia (where Zinzi Clemmons is also from and currently lives) and resides in Brooklyn. Bertino served for six years as the Associate Editor of One Story. Bertino and Clemmons corresponded via email about their hometown and the writing process.

*

Zinzi Clemmons (ZC): In nearly everything I’ve read about you, you mention that you’re from Philadelphia. I counted two stories in your book, Safe As Houses, explicitly set in the city: “North Of” and “Great, Wondrous.” Most people’s relationships to their hometowns are complicated. How would you describe your feelings toward your home city?

Marie-Helene Bertino (MHB): Philadelphia is a difficult city to explain. There is some seriously dark beauty there, and some serious dysfunction. I think the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program is an example of Philly at its best, taking what it is specifically good at — its tenacious, stubborn spirit, and the courage to take risks — to stamp the city with gorgeous murals. These murals have become the city’s complexion. You can’t go far without seeing one, and I mean from Center City to West Philly to where I grew up, in the Northeast. No other city I’ve visited looks like that. It is specific to the spirit of Philly.

A mural from Philadelphia’s Love Letter series

A mural from Philadelphia’s Love Letter series

ZC: What’s the neighborhood like where you grew up?

MHB: Northeast Philadelphia is difficult to describe. It has a surprisingly big sprawl, from the edges of the suburbs to the elevated trains of Kensington. Growing up, we talked tough and went to neighborhood dance spots every weekend. We all knew how to dance, and we wore ridiculous outfits doing it. People there are strong, stubborn, and unflinching. They have a way of looking through you if they feel you are being phony. I was a strange hippie weed growing in that garden, yet even though there is a large part of me that grew up whimsically and loving the music of the 1960s, I have that bottom-line quality. I have zero tolerance for pretension, liars, cowards, phoneys, and, worse, I’m not able to hide it. Philadelphia did that to me.

ZC: So you think the city has had a positive effect on you overall, made you a strong person?

MHB: If you don’t mind, I’d like to borrow the words of David Lynch, who I hear studied painting in Philly. I’ve never heard it put more beautifully: “Yes, [Philadelphia is] horrible, but in a very interesting way. There were places there that had been allowed to decay, where there was so much fear and crime that just for a moment there was an opening to another world. It was fear, but it was so strong, and so magical, like a magnet, that your imagination was always sparking in Philadelphia… I just have to think of Philadelphia now, and I get ideas, I hear the wind, and I’m off into the darkness somewhere.”

ZC: Any favorite writers from the Philadelphia area?

MHB: Last month I read at Tattooed Mom on South Street with Liz Moore, of whom I instantly became a fan. She has a lilting, beautiful voice. Also, a few years ago I visited a class of writing students at the University of Pennsylvania. A few of them went on to found Apiary Magazine, and I’ve kept up with their very admirable progress.

ZC: Where do you live now, and what is your writing routine like? What is your ideal writing environment?

MHB: I write in the morning when I am practically still dreaming. Ideally I wake up, start the coffee and open my copybook or laptop, depending on what stage of the process I am in. Me and the cats, endlessly happy. However, the ideal writing situation doesn’t always occur. I work full time as a biographer for people living with traumatic brain injury. I’ve also been traveling recently to teach and do readings. So, my job will intervene or someone I love will need me.

ZC: I read in your interview with the Paris Review that you’re working on a novel now. Can you describe that process?

MHB: I pour my coffee, open the windows, and sit down to work. That is when walls grow up around me that no one, including me, can see. They seal out sound and distraction and seal me in. People on the other side of them have said they’ve called my name and I haven’t heard. It’s been especially true writing this novel, which takes place on one single night. So every day I return to the same night, over and over.

When it is over and the walls are down, I have no idea how much time has passed. Hopefully I’ve excavated one good line I can think about all day and night. Upon descent back into the regular world, there is always turbulence. Another thing I’ve yet to figure out. I go for a run immediately, or get myself to a Pilates class. This helps the transition. Otherwise, panic sets in.

ZC: You mentioned cats – are there any other pets in your life? Do they help you to write?

MHB: The addition of a small rescue Papillon into my life a year ago also shook up my routine. His name is Fantastic Mr. Fox. I am still figuring out how to assimilate him. He’s so excited when I wake up I couldn’t bear to disappoint him. He must be walked at once, it’s his thing.

If you know anything about cats: their souls are older than time. They are the only living beings able to cross from world to world. They step over me as I type, a stray paw on a space bar. They have no manners. Half the time I feel like I am writing what they are dreaming about anyway. Like I am their scribe. I narrow my eyes at them. They pretend to sleep. If you know anything about dogs, they are all fresh out of the gate, soul-wise. The little Fox is left to hop and lick and sigh and stretch and sleep on the outside of these walls, which is fine with him, because I keep him stocked in juicy bones and comfy beds, and because everything is fine with him.

ZC: Your stories usually include a fantastical element or conceit — e.g. in “The Idea of Marcel,” the narrator is meeting “the idea of” her ex-boyfriend. How did your tendency to include the fantastical develop?

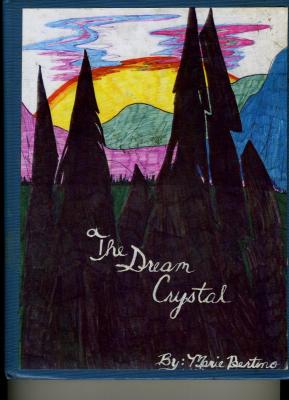

MHB: I grew up reading mostly fantasy and science fiction books. Lloyd Alexander and Madeleine L’Engle were (and are) my heroes. I wrote my first book when I was 13, and it was a fantastical girl-on-a-journey epic à la “Taran Wanderer.” She had amnesia and was the rightful queen of a fantasyland I named after my local mall, Neshaminy. Since then, nothing much has changed. I’ve always felt a sense of magic flirting at the edges of the world, and I like to explore the different ways it can manifest. I like to explore the ways the world can feel magic-less, too.

Cover of “The Dream Crystal,” written by the author at age 13

Cover of “The Dream Crystal,” written by the author at age 13

ZC: Your essay “Hyphen-Nation,” published on thecommononline.org, takes a figurative object and turns it into a material space — in this case, a hyphen, from which you narrate the essay. You describe events and experiences that seem to inspire your reflection on in-between identities — a dialogue with a Kansan girl who tries to guess your ethnicity; writing in general; your grandparents’ meeting. What inspired you to write this essay?

MHB: I tried to think of a location I would be lit up to write about, and more traditional places weren’t lending themselves to any strokes of inspiration. I can’t remember the exact moment I started thinking of my name as a place, but when I thought of that tab of space between my two first names, I thought, maybe that’s just crazy enough to work!

ZC: When we started emailing, I noticed that you signed your messages Marie, rather than Marie-Helene. Do you find yourself choosing between identities — say with your name, nationality, or occupation (writer vs. editor; writer vs. employee)?

MHB: I think a person has the right to decide what he or she is called. I’ve tried pen names, different concoctions of my name usually, before settling on just using my full, formal name. I have three years of music writing that were written under a totally different name. One thing I like about Marie-Helene is that it slows people down. They have to stop and, in many cases, ask me how to pronounce it. It cuts down on the instances of “Maria” too, though, unfathomably, they still happen. Some people use the French pronunciation, some people call me nicknames, my boyfriend has a specific name for me, the friends I’ve had since I was a little girl call me something no one else does. I like that I know how a person knows me by what they call me.

ZC: Your first book, Safe as Houses, is a collection of stories, which to me seem to all be concerned with emotional difficulty, and how characters tackle and survive it. How did this book emerge as a collection?

MHB: I was a mixtape girl, a girl who expressed love by taping songs onto a cassette I designed and painted. Later, I would burn songs onto a CD, which made it easier in a way, but I missed the well-timed “dance” I had to do to record songs onto a tape with no jerky delay. When it was time to order the stories in my collection, I thought of it as a mixtape. I laid the hard copies of the stories in front of me, and tried to imagine the flow from one story to the next. The first and last stories were the most important, as they would be charged with the first and last lines of the entire collection. After they were in place, I ordered the others, taking care to make sure the last lines (the last chords) of a story shook hands nicely with the first lines (the first chords) of the one following it. This presumes people read a collection from start to finish, which they don’t, but when you write or order a collection, why not shoot for the ideal?

Marie-Helene Bertino‘s Dispatch essay “Hyphen-Nation” can be read at thecommononline.org, and her short story “The Idea of Marcel” was published in issue No. 04 of The Common.

Zinzi Clemmons is a writer and editor living in Philadelphia.