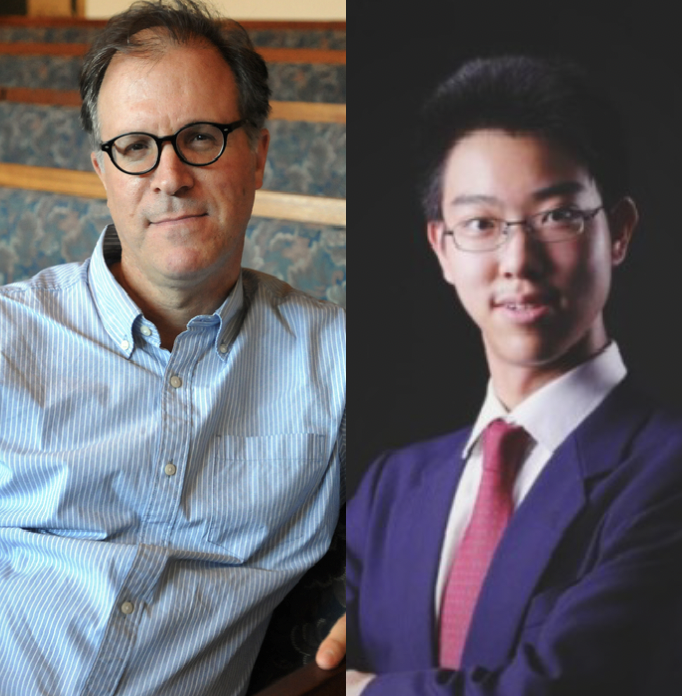

A conversation between ILAN STAVANS and HAORAN TONG

Does a poet benefit from knowing more than one language? In what way do translingual poets approach their craft differently than their monolingual counterparts? Should translingual poets be understood as “self-translators”? Is translingualism a form of rebellion? How do we make home in, across, and between languages?

These topics are part of the following conversation between Ilan Stavans and Haoran Tong. Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor of Humanities, Latin America and Latino Culture at Amherst College. He is the author of the award-winning, book-length poem The Wall (2018) and the translator into English of Jorge Luis Borges and Pablo Neruda and into Spanish of Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop, among others. Chinese poet Haoran Tong is a student at Amherst College. The conversation took place electronically in Amherst and Wellfleet, Massachusetts, from June 25 to July 10, 2021.

***

Haoran Tong: The complex relationship between language and thought is a topic that has long intrigued poets, linguists, and philosophers. As philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein famously proposed, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” While he faces challenges from some linguists and neuroscientists, generations of poets have followed his lead to explore the dialectic between language and thought through their own literary experiments. Translingual poets, for example, expand the scope of “poetic thoughts” by adding elements of multiple languages.

If we adopt a strict definition of “translingualism”— “trans” means “across, over, and beyond”—conversations across different languages may seem quite effortless. But the purpose of translingual poetry centers on “going beyond,” that is, transcending the barriers of certain languages and therefore the thoughts and ideas they constrain. This nebulous process involves death and rebirth of mother tongues, confusion and epiphany of language-specific expressions, struggles of local and cosmopolitan identities. Do languages converge or compete in a multilingual poet’s mind? Or must there be a dominant language?

Ilan Stavans: The question has been with me ever since I have had memory. I grew up in a multilingual environment. On an average day, I would switch languages—Spanish, Yiddish, Hebrew—depending on the circumstance: in school I would use one, on the street another, with a particular set of relatives a third or fourth. Astonishingly, I don’t remember ever getting confused. What’s more, these languages, unless I’m mistaken, never intermingled. Years later, when I immigrated to New York City, I discovered what I would later recognize as “hybrid tongues,” the mixing of Spanish and English (aka Spanglish), English and French (Franglais), English and Chinese (Chinglish), and so on. To the extent possible, the Spanish of my childhood was pure, and so was my Yiddish and Hebrew.

Therefore, languages do converge, though only on occasions defined by socio-economic circumstances. Conversely, languages also keep themselves apart, retaining their respective consistency. And, of course, they compete. That competition, in my view, is shaped by Darwinian forces. In a certain period, Yiddish was my dominant language. But at some point, Spanish took over. I wasn’t interested in writing at that stage, but had I been, Yiddish would have come first and Spanish second. This competition also depends on one’s audience. In Yiddish, my audience would have been negligible: my family elders, my teachers, a few schoolmates… Spanish, on the other hand, was Mexico’s vox populi.

I confess to have been rather impatient, even upset with my parents, for teaching me more than one language. Life as I understood it at an early age would have been simpler had everyone communicated in the same tongue. I only understood the advantages of multilingualism when I left home and became an immigrant to the United States. Suddenly, what I had understood as a handicap became an asset. This asset led me to become an essayist, a cultural commentator, and a translator. Today I believe that living in two or more tongues is a way of multiplying one’s perspectives. And I think to myself: does a particular language foster a specific kind of thought mode? Does my mind function differently depending on the language I’m using?

HT: My experience of being translingual is a bit different from yours, Ilan. I was born in a Chinese-language environment and acquired English later. For me, there is certainly competition, or, to employ a more aggressive word, war (invasion and defense), between the languages in my poetry. I had my first encounters with Chinese poetry at the age of 3, when I sat on my grandma’s lap and heard her recite Tang-dynasty poems. Since then, the seed of Chinese poetry—its rich history of civilization and cultural inheritance—has been planted in my mind and tongue, and my immersion in Chinese culture and language has engendered in me an identity as a Chinese poet. Chinese language, culture, and society are undoubtedly my anchor.

My English education, in contrast, focused more on practical dialogues than on literature. English was taught to me as a useful tool to acquire more knowledge, but Chinese was me. This probably explains my initial reluctance to use English elements in Chinese poems, or vice versa. Moreover, I seriously scrutinized my poems, out of guilt, for any “latinized” syntax that sounded “unChinese.” I defended the language against “mother tongue corrosion,” as Yu Kwang-chung, a cultural critic and poet, asserted. More nuanced encounters with English literature made me realize that any language gains its strength from inclusive and selective absorption from others.

My inspiration for a translingual poem often comes from the collisions in “wave-crossing”: different languages superpose like waves in different directions crossing at a fixed point. For some parts, the languages I learn cancel each other; for others, they enhance. Translingualism gives rise to more signals and greater noise. I have become more careful, as a translingual poet, to ground my ideas and images onto a specific cultural context.

I’m reminded of Poetry, Language, Thought (1971), a book by Martin Heidegger in which he links language to the pursuit of truth. The more languages you speak, the closer you are to the truth; this is an intriguing statement. How does a poet embrace or resist such confusion or complexity? Does a poet have certain faith, or perhaps loyalty, to one language over the other?

IS: First, let’s remember that linguistic confusion is a sine qua non of life. All monolinguals experience it. Is the confusion different among multilinguals? Different, yes, but not worse. Simply put, a multilingual poet has more offerings at her disposal from which to choose.

When I’m writing in it, it isn’t that I love Spanish more than Yiddish, Hebrew, or English; it is just that I have chosen it over the others in order to deliver my message. At other times, I will do the same with any of the other languages I live in. Being a rather recent arrival to the English-speaking milieu, maybe you haven’t experienced this “faith.”

HT: Perhaps linguistic confusion is exactly what makes translingual writing a fascinating literary phenomenon; it can create space for surprising cultural connections. For example, if I were to write a Chinese poem constructing an image of the moon and the willow tree, most audiences would guess it relates to reminiscence, departure, or reluctance to leave home, since “The Moon” has become a common metaphor for home. “The Willow,” pronounced 柳“lǐu” in Chinese, is a quasi-homophone character to 留“líu” (stay). If I transplant the two symbols into an English poem without much context, few readers would grasp my message. Writing translingually allows me to transform the Chinese-specific symbols into the English scene without destroying their mystic beauty. The process results in synesthesia: one might see the flower in one language and smell its scent in the other.

I agree with you that translingual writing isn’t about loving one language more than the other. However, I do believe that some poets choose an “anchor” language even though they hold the same level of passion for other languages. Like you said, the anchor might shift from poem to poem, depending on cultural connotation, message, audience, etc. If a poet’s home is their language, then a multilingual poet owns several homes. A translingual poet, I think, resides on the train that constantly travels back and forth from one home to another. For you, a mature polyglot who has been writing translingual poetry for years, the trips make perfect sense. For me, who’s still exploring the expressive capacities of an acquired language, the trips make me feel “homeless,” in diaspora. I often trap myself in the decidophobia, fearing I have chosen the wrong anchor language and, therefore, weakened my message. Maybe I still need to cultivate my faith.

IS: Decidophobia is a common social trait, especially in capitalist societies: we are constantly demanding ourselves to make a choice. This, obviously, comes with the fear of making the wrong one. Is it possible to have too many choices before us? Should one try to avoid such a situation? Probably not.

It is important to distinguish between translingualism and hybrid languages. Translingualism, as you defined it, is the travel from one linguistic code to another. Hybrid languages, in contrast, are built through combination. Spanglish, which I adore, is a prime example; it has its own rules. I recently translated Alice in Wonderland (2021) into Spanglish. If you are either a Spanish or an English speaker, you only get a portion of it, as you might when as a Spanish speaker you read Portuguese. Every poet creates her own language—and translingual poets do so by absorbing elements from whatever languages they have at their disposal. But they must choose one of them as their prime vehicle.

HT: I wonder if the “prime vehicle” you describe is the same as “the anchor language”. Would different “prime vehicles” create different mindsets, even if elements are collected from the same set of languages? Xu Yuanchong, who was known for translating Tang poems into English, told his students in 2014: “English is a more scientific language and prioritizes logical coherence between scenes, but Chinese is picture-oriented and emphasizes formal beauty among images.”

IS: I agree with Xu Yuanchong. English is precise, even methodical, maybe even to a fault. I enjoy channeling thought in it, but when faced with emotional explorations, I often find it constraining.

HT: Xu Yuanchong’s words resonate with me too. When I develop a poem using English as the prime vehicle, I think first about a central idea and arguments, then the narrative arc to unveil them. Using Chinese, I come up with a set of images, then connect them—sometimes through purely aesthetic expressions. I often don’t even have a message until I assemble the language. Of course, if I were not multilingual, I wouldn’t even realize the difference in the process. Is this discovery of linguistic phenomenon enough to make poetry truly translingual? Should translingual poets treat the languages as the end, instead of the means to expressing transcultural ideas?

There are poetry critics who believe that translingualism makes poetry weaker, as “counterfeit” or “betrayal”. Can we view translingual writing as a process of translation, re-translation, and pseudo-translation of works in one particular language?

IS: I’m well aware of this criticism. I remember listening to Stanisław Barańczak, the translator of Polish poet and Nobel Prize winner Wislawa Szymborska, make the same argument. His thesis was that translingual poets have a more limited lexicographic reservoir. My initial reaction to Barańczak was that he was right. For a long time, I nurtured an inferiority complex vis-à-vis natives, sensing that they had and always would a far vaster, more robust vocabulary. But I’ve lived in the English-language habitat now longer than in other linguistic realms. I see myself as a religious convert who, after a long period of studying, knows more about the new faith she has embraced than those born into it, simply because she chose it. The natives take their language not as a gift but as given. I now believe a non-native poet, and particularly a translingual poet, makes poetry stronger.

HT: In the American context, being non-native and particularly translingual screams politics to me. Writing translingually challenges the presumed centrality and “nativity” of a language in a nation. Lydia H. Liu and Ruth Spark describe translingualism as a practice that encodes processes of domination, resistance, and appropriation. Translingual poets in the US actively resist settler colonialism by displaying the diversity of their mother tongues on top of English— “the American language.”

IS: I disagree with Liu and Spark. I don’t believe translingualism is a subversive praxis. There are scores of places on the planet where the vast majority of speakers are polyglots. In fact, one could argue that monolingualism in such locations is rebellious. I also don’t believe translingualism is anti-colonial. Colonialism thrives through polyglot strategies.

I want to go back to Xu Yuanchong. One of his theses—rather controversial, in my view—is that a translator competes with the poet in making the best possible version of the poem. Of course, there is a second competition: between the translation and the original. I won’t argue with the idea here. Instead, I want to link it to our conversation about translingual poets. The translingual poet, in choosing the appropriate language in which to write a piece, competes with herself—that is, with avatars of herself.

HT: To me, the most fascinating part of translingualism is ultimately not what is translated but what is untold or needn’t be told. A translingual poet legitimizes the “misuse” of language(s): the organic, creative engagement of possibilities unforeseen through the lens of any single language. Competing with herself in a poem of different languages, she detects and derails from constrained patterns or cliches. While she isn’t literally translating, she is transplanting the syntactic, dictional, or symbolic advantages of that language into an otherwise underwhelming monolingual poem. And she simply leaves the translingual complexity there for the audience to explore. Whereas translation tells, explains, or instructs, translingual writing shows, infuses and liberates.

IS: Translation and translingualism in poetry are two categorically different endeavors. The first one seeks to bring to the target language a text that originated in another linguistic realm. Translingual poetry might play with various linguistic realms but ends up privileging one. The translingual poet does some translation but only to achieve certain creative effects.

Let me ask a final question: if language shapes thought, does a multilingual poet have alternative ways of thinking that differ from a monolingual? To me this goes to the heart of the matter. A translingual poet does think in different modes. Understanding those modes takes substantial time. They come after years of getting acclimated to the essence of a language.

HT: I do believe multilingual poets have the capacity to think in different languages, which helps them produce more creative and imaginative poetry. I would characterize translingual poetry writing as a meaningful detour from a set path. It aims to inspire, not foreclose; to pose questions, not dictate answers. As long as one gains faith from confusion and rescues her voice from noises, one would find her mission.