MELODY NIXON interviews JONATHAN MOODY

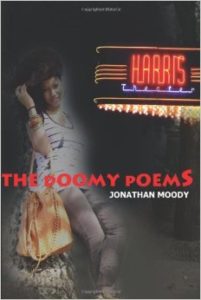

Jonathan Moody is a poet and professor. His first full-length collection, The Doomy Poems, deals with time and place through persona poems, and is described by Terrance Hayes as having an “innovative funkiness that transcends the ruckus and heartache of our modern world.” Moody’s second poetry collection, Olympic Butter Gold, won the 2014 Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize and will be published in summer this year. His poem “Dear 2Pac” appears in Issue 08 of The Common, and his “Portrait of Hermes as a B-Boy,” “Kleosphobia,” and “Paranoid,” have all been featured at The Common Online. Melody Nixon caught up with Moody this winter, and between New Zealand and Texas they talked poetry activism, politics, Houston skyscrapers, and the “cosmopolitan radiance” of Downtown Pittsburgh.

Melody Nixon (MN): You live in Fresno, Texas. Where do you write? Can you describe the environment around you

Jonathan Moody (JM): I usually write poems in the privacy of my study. As far as my environment is concerned, Fresno is a location that could’ve easily wound up in a Sam Peckinpah film because it is rural-urban. You’d see an energy corporation’s new gas station eating up stretches of grazing land. You’d see stray pit bulls running laps around subdivisions. And there’s Hightower High School’s magnificent football field. On Friday nights, the stadium lights cast their brightness onto the walls of my living room; at times, I’ll hear the announcer yelling “First down!” followed by the roar of the crowd. Fresno is a tiny, tiny city: so tiny you could drive through three traffic lights and end up in a completely different zip code. My hometown is ensconced between Missouri City, which is where my wife grew up, and Pearland, which is where I currently teach.

MN: Where else have you written? Are there any places that stand out as especially difficult, or especially conducive, to words?

JM: I’ve written in Houston, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, Ft. Walton Beach, and Destin. All of the cities I’ve listed are conducive to writing. My first book, The Doomy Poems, takes place in Houston and in Pittsburgh. What makes these cities especially conducive to words is that they are gorgeous at nighttime. You haven’t lived until you’ve driven on I-45 and caught a view of the Houston skyscrapers or driven through Fort Pitt Tunnel and watched the cosmopolitan radiance of Downtown Pittsburgh’s golden bridges reflecting off the Allegheny River.

MN: Your poem in Issue 08 of The Common,“Dear 2Pac,” describes a poetry teacher having a breakthrough moment with a student by prescribing Tupac as reading. Can I ask the taboo question, since you’re a teacher: how autobiographical is the poem?

JM: Oh, the “I” in the poem is all me; “Dear 2Pac” captures the magical moment that happened in my classroom! The only thing that’s fictional in “Dear 2Pac” is the student’s name. Even though the poem does illustrate a breakthrough moment with a former student, what’s bizarre is that it was a breakthrough poem for me.

This response ties back to your previous question. When I left Pittsburgh in 2007 to move to Houston, and eventually to Fresno, I had a hard time adjusting to my new surroundings. I didn’t realize the impression that Pittsburgh had made on me until I inhabited a different landscape. I wrote a few poems that were garbage, but a brother was blocked for eons. During this time, too, I was experiencing life-after-the-MFA and had no idea that landing a decent teaching gig in Houston was going to be tougher than landing a space shuttle. I became salty (as my students would say) to the point where I thought poetry no longer mattered. So, I quit writing. Cold turkey. Then, in 2011, an underachiever named “Daniel” made me eat my words, and I’ve been writing ever since.

MN: How much was the agency of your subjects a consideration when you wrote that poem?

JM: I’d make the claim that agency, or the lack thereof, served as one of the main catalysts that lead me to write “Dear 2Pac.” When it comes to certain types of literature, like poetry, the majority of my students feel helpless. For years, they’d been exposed to a rigid curriculum sorely lacking in contemporary practitioners. For years, they’d been trained to ascertain poetry according to objectives and college readiness standards that reduce poems to multiple choice. When they encounter poems written centuries ago, it’s not surprising to see them panic or put their heads down on their desks. Literature is a discipline that can portray the agency of its characters/speakers and should, in turn, encourage agency in its students to become independent thinkers. Some of the poems from The Rose that Grew from Concrete gave students the confidence to take ownership of the language and eventually the discussion. It also gave me the confidence/agency to include supplementary texts that stand on the periphery from the canon.

At the 9th, 10th, and 11th grade levels, there’s hardly room for deviation in Texas (in theory). But I later encountered lesson plans online from a middle school educator in my same district who was using Biggie Smalls’s song “Juicy” to teach literary elements. The idea, though, to implement “Dear 2Pac” happened spontaneously, and I teach 12th grade: meaning that I have more flexibility to teach outside of the box’s box.

MN: Your poem “Paranoid” appears online at The Common. It has some chilling lines, especially in light of 2014 and police brutality in America.“I’ve passed down my fear / of the police to my baby boy / who always sleeps, frozen / with his hands in the air.” Those are beautiful lines, and not necessarily with political intent, but I wonder, does your writing ever get labeled as “political?” Sometimes writing that addresses Black experience is labeled ‘political’ (by non-Black readers, for the most part) merely for the fact it shows Black culture or experience. Does it bother you when that label is applied to writing by Black authors?

JM: I’ve never had anyone refer to me as a political poet, but I can imagine that when my second book, Olympic Butter Gold, drops in the fall of 2015 people will refer to me as such. The book addresses Black culture (i.e. Hip-Hop) and my experience of coming-of-age as Hip-Hop came of age during the eras of racial profiling and domestic surveillance. But there are also poems about love and fatherhood in the collection, and some readers (non-Black or Black) might still interpret those pieces as political poems even though they weren’t written “with political intent.”

MN: If they were written with any sort of intent, what was it?

JM: On the question of intent—I feel that there’s another question hidden in your inquiry pertaining to the initial stage of my writing process: the issue of whether or not I say, “Today, I’m going to write a political poem.” Absolutely not. All of what I write is based on what I’ve read, experienced, and/or imagined. For example, the first lines you referenced from “Paranoid” weren’t explicit responses to Oscar Grant or Trayvon Martin. The poem was originally inspired by the irony behind a stranger who broke her neck to get a glimpse of my infant son’s chubby cheeks without realizing that she, like the police, might one day see him as a threat. I wrote the opening lines to “Paranoid” in January or February of 2014 in the midst of a New York Undercovermarathon while I was also watching [my son] Avery Langston sleeping in his bassinet. It’s wild now not only to see online images of congressional staff members holding their hands in the air as a sign of protest in response to the cases of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, but also to see Facebook and Twitter status updates including the statements “#blacklivesmatter” and “#blackpoetsspeakout.”

MN: Yes, there so many examples of hashtag activism, some of dubious intent and some to dubious effect. Not to backtrack, but I’m curious, in the context of recent activism: what do you think about the notion of political poetry?

JM: In an interview from Black Books Bulletin 2 that was reprinted in Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks, Brooks mentioned that she didn’t mind the word “political” being applied to Black poets; I’m not bothered by it either except when “political” becomes code speak for “polemical,” “preachy,” or “angry.” A popular, duplicitous word I’ve heard some white authors use recently is “topical”: as in, “Don’t write ‘topical’ poetry,” which I believe could stem from some deep-rooted guilt as in: “Don’t write ‘topical’ poetry that makes it difficult for me to defend how we live in a post-racial society.”

As far as my musing on political poetry, it’s valuable so long as authors are willing to find different angles or to create what I like to call subtle nuances. For instance, the subtle nuance in my poem “Paranoid” pertains to the surreal adjustment I made to a popular nursery rhyme that indicates the absurdity behind racial profiling (especially when the suspect is a baby): “Corralling around dancing / clouds, Lil Bo Peep’s / sheep wag their badges / behind them.”

MN: Can/should poetry be used as a tool of activism?

JM: Poetry can be used as a tool of activism whether you have military wives posting pictures of poems written on their naked bodies as a way to promote awareness of PTSD, or Cave Canem poets using social media to post video footage of them reading poems about police brutality.

I’m also thinking of the phenomenal experiment that André3000 conducted during the recent OutKast reunion tour. Given his hesitancy to perform old songs from the Kast catalogue primarily to support his family, 3000 felt like he’d sold out and believed he couldn’t possibly say anything new to keep the show fresh. So, he came with this idea to wear black jumpsuits with poetic koans plastered across his chest. All 47 of them went on to be featured at Art Basel Miami Beach and will be on display this summer at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia.

MN: That’s a strong example of the potential for overlap between poetry, visual art, and performance. Do you have any plans to (or current projects that already) work across disciplines?

JM: Not at the moment, but I won’t rule out the possibility. One writer who inspires me is Troy CLE: author of The Marvelous Saga books. Whenever he visits schools and converses with children, he uses his background in graphic design to immediately grab the audience’s attention. Before he even reads his fiction, he’ll project a stunning image of the antagonist from his novel and will proceed to say something along the lines of: “The language in this book is more stunning than the graphics on your Xbox.” Graphic designing is not one of my talents, but I could see myself creating a digital collage of album covers and/or artists (i.e. musicians, songwriters, and authors) that inspired me to write Olympic Butter Gold. I could see myself presenting this collage before reading to a group of children.

MN: You also work collaboratively, and you’re working on a project with poet Myron Michael. Can you tell me what that involves?

JM: Yeah, Myron approached me with the idea to collaborate on a book of poems that addresses our experiences of growing up with Hip-Hop culture. Being that I’m a Hip-Hop head and I’d just become a parent, he wanted to see my angle on fatherhood as it pertains to Hip-Hop. The timing was perfect because my son was born in 2013: the year Hip-Hop turned 40. Also, I was in the process of completing my Olympic Butter Gold manuscript before submitting it to book contests. So, it became a little easy for me to become settled into his vision, so-to-speak.

We would send each other works-in-progress and offer feedback. I’m amped because the poems Myron submitted to me were fire. I have several more poems to write, but l have a few ideas circulating. For example, this weekend my Uncle Melvin and I are going to see Rakim and EPMD perform at Houston’s Arena Theatre! As a kid growing up in a small town called Fort Walton Beach, no rap acts came through my area. So, it’s cool that I’ll soon witness East Coast rap legends moving the crowd.

MN: You mentioned earlier that you gave up writing poetry for some time, post-MFA. I imagine the decision to return to it has felt worthwhile for you. What would you say to writers, poets or otherwise, who are in a similar state of being stuck, as you were? Should they get back on the page, and if so, why?

JM: No question. If all you think about is writing, then you should dedicate your life to it (regardless if you share your work with others or not). Don’t base your success on the number of acceptance letters that you receive or how marketable you appear on your C.V. If you find yourself in a rut, then allow life to happen. Junot Díaz said something along the lines of: don’t let the market determine how much material you should produce. Allow the art to have its way, which is great advice because it can help eradicate the pressure of, dare I say it, “sustaining momentum.”

*

Jonathan Moody’s poem “Dear 2Pac” appears in Issue 08 of The Common.

Melody Nixon, a New Zealand-born writer living in New York City, is the Interviews Editor for The Common.

Photo credits: Pittsburgh Night Skyline, by Ronald C. Yochum Jr., via Creative Commons. Pittsburgh Skyline, by Robpinion., via Creative Commons.

Houston Skyline via Creative Commons.