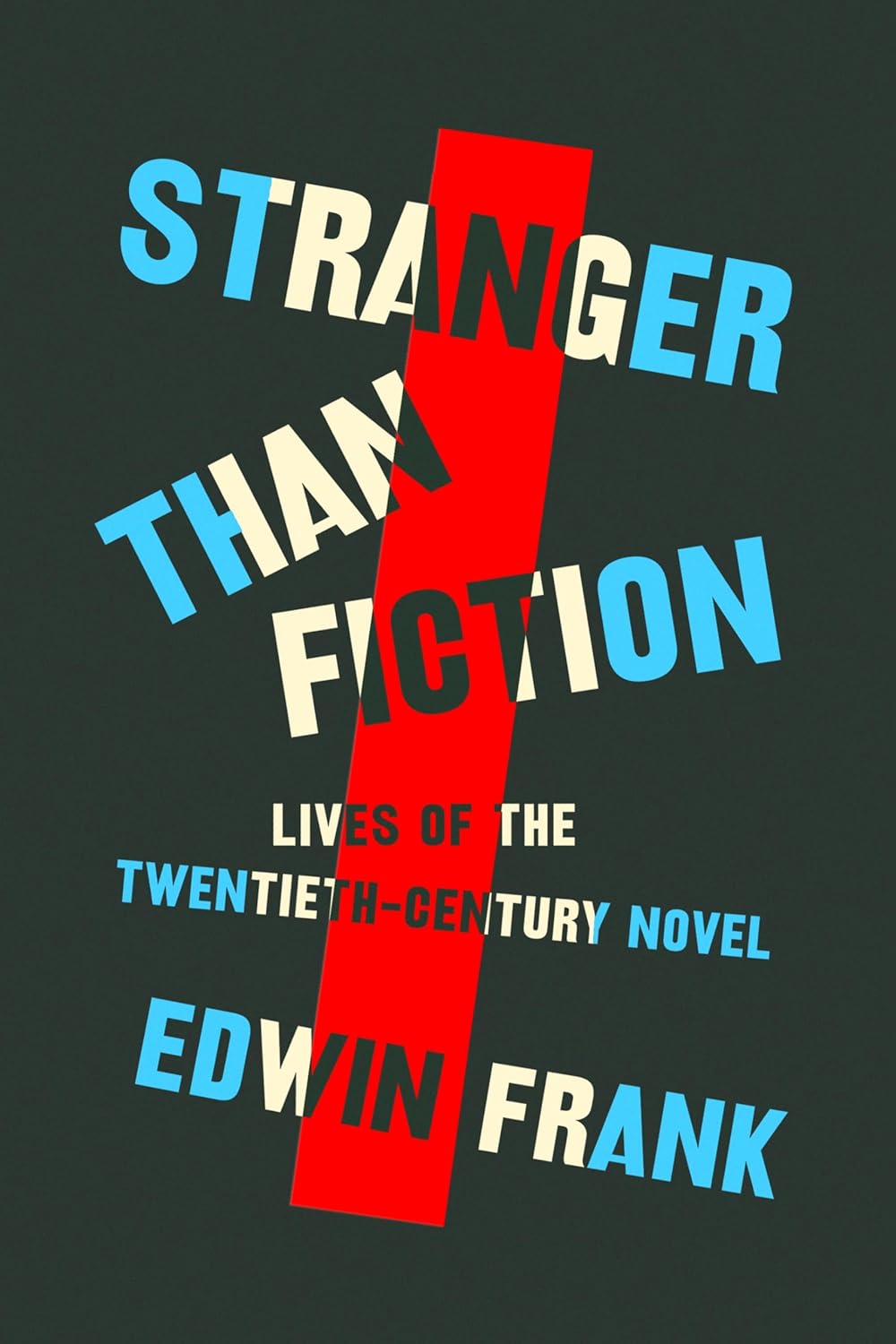

I picked up Stranger Than Fiction, Edwin Frank’s relay race through the twentieth century novel, immediately after rereading Madame Bovary, only to encounter Emma Bovary, who came into the literary world in 1856, in the first chapter.

Frank isn’t simply paying obligatory homage to Flaubert’s importance to the nineteenth-century novel. He’s pointing out the cinematic modernity of the famous agricultural fair scene which splices the full-of-himself aristocrat Rodolphe seducing Emma, the country doctor’s bored wife, with pompous local officials making speeches. He’s also showing that the nineteenth century novel, with its formidable, reality-affirming scenic machinery, was still in full flower when Fyodor Dostoevsky’s radical and baffling Notes from Underground, which Frank pegs as the first twentieth century novel, emerged barely a decade later. If the nineteenth-century novel “attempts to maintain a dynamic balance between the self and society,” the exterior world barely seems to exist for Dostoevsky’s narrator, whose mind churns through semantic and philosophical problems for much of the text. Yet, the book was anchored in reality—the political and social problems of Russia and the personal torment of its writer—in a new way.

Among the difficulties of writing a wide-ranging work of criticism like this is to keep readers interested in the books or authors they haven’t read. It was great fun running into the appalling, impossible and familiar Emma. What kept me reading Stranger Than Fiction was what I didn’t know. In other words, I read it like a novel.

Frank weaves the lives and work of thirty writers who redefined the novel, the era, and themselves into a story, each in their own way struggling with how to write amid previously unthinkable possibilities unleashed by violence and technology on society, sexuality, and language. What propels the book—an unusual verb for a work of critical literary history—is its sense of an eclectic, far-flung bunch in a collective endeavor (whether they know it or not)—writing against time in a doomed world.

Frank, the editor and founder of New York Review Books Classics, which has pioneered republishing out-of-print or underappreciated classics and translations, takes pains to tell us what the book isn’t: a canon or a survey of how key moments of history found their way into fiction; or how authors responded to those moments; or artistic movements with names that have lost their specificity like “modernism.”

To fashion a meaningful literary “roll call” (in Frank’s words) of the thousands of influential, significant, and just plain good novels written in the last century in multiple languages and countries presents staggering category problems, starting with: What’s a twentieth-century novel? (Not necessarily one published in the twentieth century, as we already know.)

One way he stays ahead of the category problem is by constantly refining and defining his project—reframing in terms of process rather than scope, style vs. subject, cultural influence and competition, akin to the way the narrator in Proust’s Albertine Disparue (whose lover left him, then died) tacks from jealousy to obsession to forgetting to meditation on alternate personalities to a malicious anecdote told by a possible lover of Albertine’s—all in the service of defining grief.

The twentieth-century novel is a “fictional character in its own right.”

It “emerg[es] from the nineteenth century as a robust presence with a tenacious worldly curiosity and a certain complacent self-regard, a form that was both ready to shake things up and asking to be shook up.”

It’s “a useful fiction for considering how fiction responded to a century of fact.”

The twentieth-century novel is a “category of novels that have made it a point to puzzle over what they, the century and the novel, were doing together and how, in effect, they were to get along…”

“… an art form of extraordinary amplitude put under unprecedented stress … and certain novels … respond to that form by radically reshaping the novel as a literary form.”

And so forth.

The balance between momentum and cohesion comes from those shifts in emphasis, the stretchy ligatures. The prologue which features Notes from Underground takes us from Dostoevsky’s tormented personal life (his wife, his mistress, his brother); the off-handed way the book came into being (he had space to fill in his magazine); rewinds fifteen years to his near-death experience—literally, when the tsar had him arrested, along with other political dissidents and staged their executions—halting only at the moment of pulling the trigger, followed by four years in a prison camp in Siberia. Notes from Underground was smelted in this crucible.

From his opening words—“I am a sick man…”—the mad, ranting, solipsistic narrator of Notes from Underground, is, as Frank puts it, “the voice of the twentieth-century novel,” and an archetype, the Underground Man, placed in an archetypal setting, the Urban Wasteland. The end of the prologue picks up with Dostoevsky’s love life and utter contemporary indifference to the book, which went on to influence writers well into the next century and this one.

The first chapter, carrying on from Flaubert and Henry James, the masters of the nineteenth century novel, singles out H.G. Wells, born in 1866, who pioneered science or speculative fiction. The tie-in is a famous falling-out that echoes genre vs. literary/high and low arguments today. James, initially supportive of the much younger Wells’ work, called his writing unmotivated, without interiority, in a review ending the friendship. Wells was already an immensely popular writer and influential public figure and continued to be so long after James’s magisterial, difficult, sexless novels about money, status, refined cruelty, and incidentally love became an acquired taste.

Other protagonists in this saga range from the inevitable—writers who “have something to prove,” in one of Frank’s definitions, who set about changing writing and the novel—Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka, and André Gide—to the oddballs who are “mercifully, or mercilessly free of the impulse to convert the reader, moved by their own peculiar concerns and quirky talent more than they are big questions of art and the big questions of the day.” He includes Italo Svevo and Jean Rhys in this rank. Then, there are the popularizers, including H.G. Wells, Colette, and Rudyard Kipling.

The World War I generation dominates. As do European writers, literary and popular, reflecting the concentration of cultural centers, readers, publishing, and literacy. With varying degrees of awareness and contact, they latch onto each others’ innovations and propel the whole enterprise of the novel forward. One of the most intriguing connections starts as a rivulet in late nineteenth-century Brazil, a literary backwater at the time, and becomes a great river of international fiction. The realities of Latin America don’t fit into the mold of European nineteenth-century fiction, despite a certain nostalgia for belle-époque style. Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis, the mixed-race grandson of a slave in a country that only abolished slavery in 1888, had aspired to write a realistic nineteenth-century European novel about Brazil. Disappointed in his efforts, he wrote The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, published in 1880, a genre-busting novel from the point of view of a self-proclaimed nobody, but a wealthy one, who has just died. It was about 200 pages long, 160 chapters, and ends “I had no progeny, I transmitted to no one the legacy of our misery.”

Fast forward to 1953, we find Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier’s The Lost Steps, which Frank connects to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita through their protagonists—middle-aged, sexually frustrated, over-educated men, who share a “fancy prose style”— Humbert Humbert’s famous phrase about the defining characteristic of a murderer. Carpentier turns out to be a direct precursor of magic realism, leading to Gabriel García Márquez and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Essentially, the twentieth-century novel’s evolution is a form of globalization with the flow of influence outward from Europe, then hybrid forms circling back to change the original. About a decade into the century, we meet Gertrude Stein, an American expat in Paris for much of her adult life, whom Frank credits with shaking up the American sentence, paving the way for writers as diverse as Hemingway, Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, and Jack Kerouac. Frank singles out Stein’s Melanctha, a novella, the longest in her book, Three Lives, the story of a fierce and lonely Black woman in a two-dimensional Black world, narrated in a vaguely Black folk-tale voice, published in 1909. (This chapter of the book was published in The Paris Review in September, 2024.) Frank equates the character’s name, also the title with melancholy (black bile in Greek), though melano, black, seems sufficient, given Stein’s eliding of skin color and character, as in “sullen childish cowardly black Rose” or “a subtle intelligent attractive half-white” or “that ugly awful black man” or “a simple kindly colored man.”

Melanctha is the most perplexing and controversial example in the book. To this reader, the story looks on the page and sounds like a case of voice or authenticity more than sentence—though one could argue that voice and sentence both boil down to word and syntax, which still leaves the definition of dialect and accent hanging. The racist language is very much of its time. Is it a parody of racism or colorism? It’s not funny. She was a graceful, pale yellow, good looking, intelligent, attractive negress, a little mysterious sometimes in her ways, and always good and pleasant. Or: “she had much white blood and that made her see clear.” The work was essential to Stein’s development as a writer, Frank tells us. Stein had never felt at home in America. This way of writing “was her way of being an American writer … at this moment of revelation, she would have an unwavering sense of prophetic purpose—to free American literature to be itself.”

Reading Melanctha, I wanted to understand how it could be more innovative and influential to the American sentence in its time and over the life of the twentieth-century novel than American Black writers or maybe better put the Black voices it approximates. Frank steers clear of literary identity politics and polemics, a strength of the book. Yet, I found it impossible to bat away the question.

Frank credits Ralph Ellison’s 1947 novel Invisible Man with putting the Black novel at the center of the American novel, the twentieth-century novel, and the novel internationally, reflecting its engagement with Communism as well as racism and its original American, Black voice. The section on Invisible Man, the only novel by an American Black writer on Frank’s roll call, emphasizes how Ellison’s prose—sentence, voice, story, emotion—is in chorus with Kafka, Wells, and Dostoevsky, an inspiration Ellison cites in his introduction to the 1981 edition. (The opening line—“I’m an invisible man.”—echoes Dostoevsky’s Underground Man.) That said, Ellison’s Black characters speak in many vocal styles, southern, northern, rich, poor, preacher, street dude, their distinctiveness being the point. The central imperative of the American novel is fashioning an original voice, Frank says. He defines Ellison’s originality in multiple ways. One that stood out for me was “polyphonic.” Another is harder to parse: Ellison, Frank says, will redefine the problem by “speaking in a voice that is original precisely because it is the [my emphasis] American voice, the black voice that America for most of its history not only silenced, but has been premised on silencing.” It sounds like Frank is saying that the stifling is what makes the Black voice or Ellison’s voice original. Certainly, anything silenced is altered. Listen to a muted trumpet. Yet, Black voices resonated loudly and irresistibly in the American soundscape—in song, theater, not to mention ordinary speech, despite oppression, well before Melanctha. The Harlem Renaissance was in its heyday when Stein was at her most influential.

Frank says Stein’s early readers took the language of Melanctha as Black American dialect. Richard Wright wrote that he heard the voice of his own grandmother in the story and read it to an “illiterate” [Wright’s word] audience of Black workers, who responded with delight and recognition. A much less indulgent Janet Malcolm wrote in a May, 2003 piece about Stein in The New Yorker, that Melanctha, “which for many years was celebrated as some sort of wonderfully advanced study of black life by a white writer (and, by today’s less ridiculous standard of what is advanced, can only be called patronizing and uncomprehending).”

One could make an analogy to “Porgy and Bess,” the George Gershwin opera, a white interpretation of Black music and Black life—still criticized as appropriation—but which contributed some of the most played tunes of the jazz repertory. Just as Black music is the bedrock that Gershwin drew on, wouldn’t authentic Black voices be at least as fundamental to the American sentence—spoken and written—as the ersatz Black voice of Melanctha?

Frank seems to be saying that Melanctha, along with Stein’s other experiments in liberating the sentence from syntax and literal meaning, stands on its own. The racism embedded in the language or Stein’s fascist-friendly politics—despite being Jewish, she wrote propaganda for Maréchal Pétain, the French general who capitulated to the Nazis—are a separate subject.

This is distinct from the way he discusses Nabokov’s virtuosic sentences (“of such consciously licked finish”) and Lolita: “Supremely polished, this is an ugly book”—letting neither the reader nor the writer nor the attitudes of the era off the hook in their response to a brilliant and alluring book about child abuse. (To be sure, Melanctha isn’t the moral or cultural or popular equivalent of Lolita or Porgy and Bess, but it continues to fascinate and upset readers and scholars.)

Perhaps, a discussion of the influence of Black voices or more broadly non-standard voices (Jewish, Brooklyn, Southern) on American English, written and spoken, and literature doesn’t fit into Frank’s taxonomy. Maybe this is what he means by: “The truth about America is unspeakable, which is why we need new forms of speech, new and different novels to begin to understand it…”

The book’s subtitle, “Lives of the Twentieth Century Novel,” throws a gauntlet to E.M. Forster’s Aspects of a Novel (1927), originally a lecture series at Cambridge University’s Trinity College, but a standard reference now, part of the mental furniture of any MFA student. Forster’s lectures were aimed at writers and took the machinery or “aspects” of the novel—story vs. plot, flat characters vs. round ones, rhythm, fantasy etc.—as points to jump into specific books. Forster dismissed the notion of organizing novelists by chronological period or conventional critical criteria. Rather, after inviting us to picture them writing together in a circular room (why circular isn’t clear)— he compares anachronous pairs of excerpts to show their similarities, “tricks of style,” etc. across time. Forster’s argument was that human nature doesn’t change and that neither he nor anyone but the rarest of scholars had read enough to generalize and such people invariably dwelt on irrelevant details.

Forster’s point has validity, but as writers we are inevitably of our time, and readers are too. And Frank’s non-linear way of making connections does have “a writers together in a circular room” aspect.

Frank’s book doesn’t have a whiff of the writer’s manual about it. But it speaks to writers through its empathy for the unpredictable and often accidental way that a work emerges from a writer’s psyche and its cultural cauldron.

Fittingly, the twentieth-century novel’s run ends not on December 31, 1999 but in 1986 with V.S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival, in which a successful novelist from Trinidad holed up in a cottage on an old estate gropes his way into a novel about himself at the end of empire. What of the twenty-first-century novel? One quarter into the century, Frank says, the most notable trends are retrograde forms—autofiction; Sally Rooney’s novels of love, manners, and society “indistinguishable from Sense and Sensibility”; Hillary Mantel’s masterful trilogy about Thomas Cromwell. Will attention-killing technology kill the novel, along with democracy, human rights, and the environment? Stay tuned.

I suspect writers and other readers who pick up Stranger Than Fiction will have read some—perhaps many—of the books cited. Some are monstrous tomes—Proust, Ulysses. Time, boredom, the end of grad school, children, lack of relevance, the Internet, make those books hard to pick up once the monstrous-tome-reading phase of life ends. I was in Paris on a literary trip after reading Frank’s book. I’d read Proust’s first two volumes years ago, while living in Paris and again in grad school. Spurred by the feeling of “temps retrouvé,” I picked up Albertine Disparue, and read it through, fascinated by its involuted, modern weirdness, kinkiness even. Literary companion is a stodgy word for books that illuminate one’s reading, which Stranger Than Fiction does. More than that, it invites you to read along and spar with it—like a tolerant literary acquaintance who’s read far more than you but is game to talk about books.

Julia Lichtblau’s writing has appeared in The American Scholar, The Museum of Americana, American Fiction, Blackbird, Narrative, The Florida Review, and The Common, where she was previously a book review editor. After a journalism career in New York and Paris with BusinessWeek and Dow Jones, she earned an MFA in fiction from Bennington College. She was a fellow of the CUNY Writers’ Institute, 2023-24.

Her first original fiction in French, “L’Empoisonneuse,” will appear in Volutes, a new French literary magazine. A chapter of her novel, The Glass House, was a finalist in the Winter 2024 Narrative Contest. Another chapter was longlisted for the 2023 Disquiet Prize.