December 2022 Poetry Feature: Kevin McIlvoy

Poems by KEVIN McILVOY

Editor’s note: In October a friend told me about Kevin McIlvoy’s recent passing, days after I had read and been deeply moved by the following poems. We are honored to offer them to you here.

—John Hennessy

Kevin McIlvoy, known to his friends as Mc., published six novels, a story collection, and a collection of prose poems and flash fictions. A long-standing faculty member in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers, he was my colleague but, more importantly, my friend. Mc. loved books and, like many writers, he loved them so much eventually the only way to love them more was to add to them by writing. These poems were sent out prior to his death on September 30, 2022. He is missed by many, but thanks to his work, his voice is still with us.

—C. Dale Young

Most-Read Pieces of 2022

As 2022 comes to an end, we want to celebrate the pieces our readers loved! Browse our list of 2022’s most-read pieces to see the writing that left an impact on our readers.

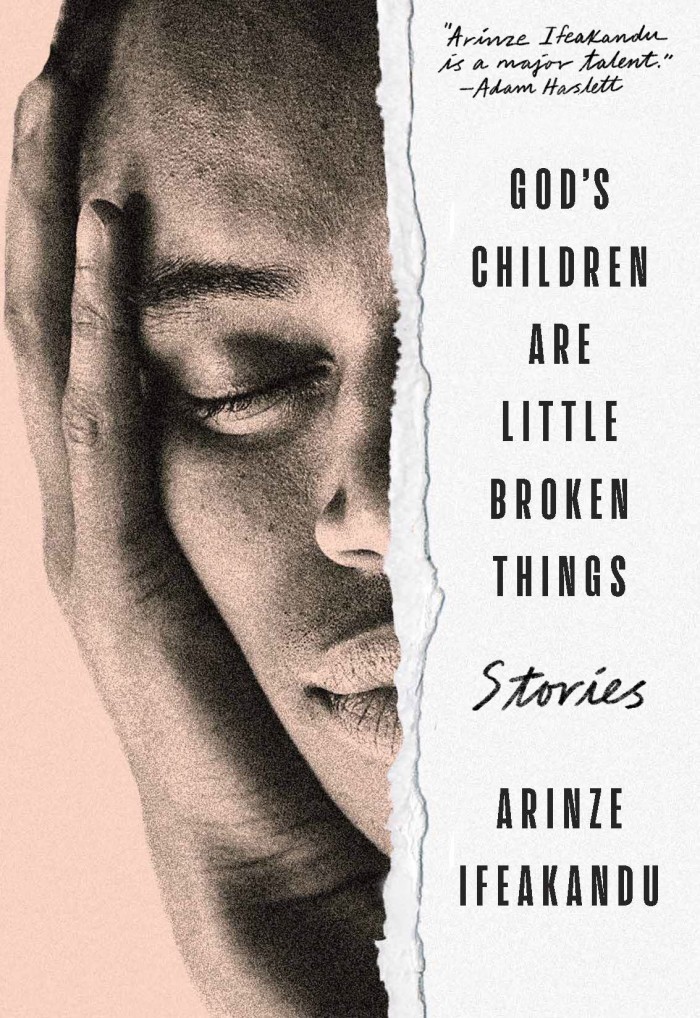

Review: God’s Children Are Little Broken Things

By ARINZE IFEAKANDU

Reviewed by JULIA LICHTBLAU

Though I’d heard Arinze Ifeakandu read from his debut collection, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, at its launch at Greenlight Books in Brooklyn in June 2022, I was unprepared for the force and distinctiveness of his writing when I opened the book. Soft-voiced and diffident, Ifeakandu seemed overshadowed that night by his effusive interviewer, Brandon Taylor, who hailed his arrival as a new gay Nigerian writer and fellow graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop on the literary scene. The stories in Ifeakandu’s collection merit reading for their subtle explorations of the nuances and hazards of living as a gay person in Nigeria, where open homosexuality is subject to federal criminal penalties and punishable by stoning in some states.

The Way Back Home

By S. G. MORADI

Iran

We grew up on salty rocks, collecting bullets,

holding onto hope as if it were a jump rope that

come our turn, would go on spinning forever

our feet never failing us.

We ran through sunburnt alleys, kicking up

clouds of dust that were quick to settle

as if somehow knowing

that we had nowhere else to go.

December 2022 Poetry Feature

New poems by our contributors: TOMMYE BLOUNT, ROBERT CORDING, REBECCA FOUST, and LUISA IGLORIA

Table of Contents:

Tommye Blount

—An Extra Steps into the Robe

Robert Cording

—The Book

Rebecca Foust

—Field

—War and Peace

Luisa A. Igloria

—Enrique Remembers Melaka Before Disappearing from Known History

Learning from Las Vegas (Air) Strip

By ZOE VALERY

This woman in the airport is neither catching a plane nor meeting one. (…)

Why is this woman in this airport? Why is she going nowhere, where has she been?

—Joan Didion, “Why I Write” (1976)

In the margins of the Strip, planes shimmer in and out of Las Vegas. I photographed this periphery, populated by plane watchers. Why they watch and why I write seem to be connected by a tenuous link that became clearer as the afternoon transpired.

*

Sundown marks the time and the place for a discreet show among Las Vegas locals. At the golden hour, vehicles on Sunset Road veer toward McCarran International Airport and park in front of the runway. While the casino-jammed stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard known as the Strip blinks itself awake in the background, the airstrip stages a steady stream of landings and take-offs. Every day, new and seasoned plane watchers come here to view the aircrafts rolling between the sky and the Vegas skyline.

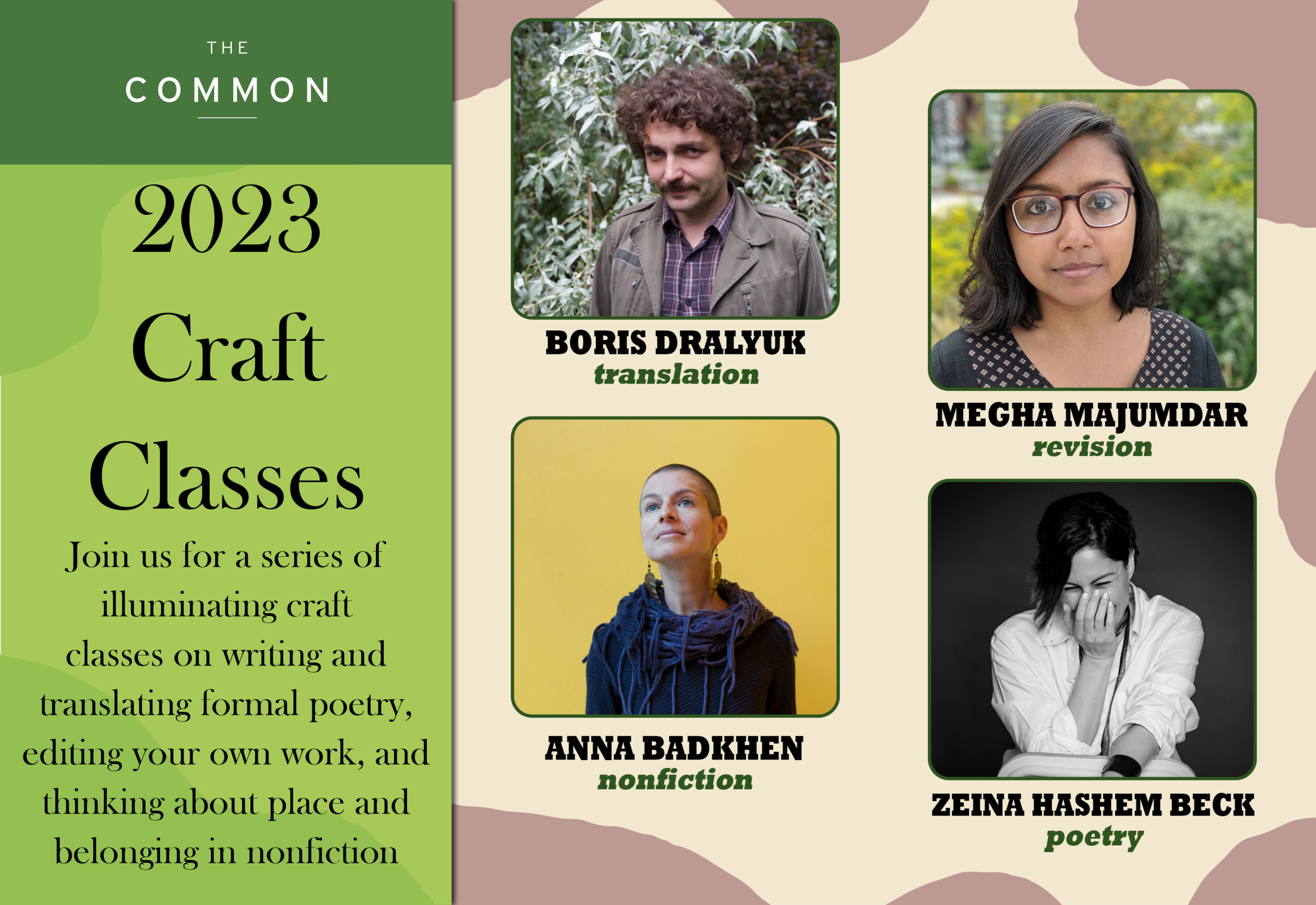

Craft Classes: Translation, Nonfiction, Revision, and Poetic Form

Give your writing a boost this winter. Join The Common for a series of craft classes with these literary luminaries.

-

-

Boris Dralyuk: “Extraordinary Measures: Translating Formal Poetry” [register]

-

Anna Badkhen: “Writing about Place: Geography, belonging, historical context, and the implications of our gaze” [register]

-

Megha Majumdar: “Demystifying Publishing and Being Your Own Best Editor” [register]

-

Zeina Hashem Beck: “The Ghazal and the Poetic Leap” [register]

-

Each class includes a craft talk and Q&A with the guest author, generative exercises and discussion, and a take-home list of readings and writing prompts. Recordings will be available after the fact for participants who cannot attend the live event.

Permission to Dream Forth: An Interview with Arisa White

JULY WESTHALE interviews ARISA WHITE

In Arisa White’s lyrical memoir, Who’s Your Daddy, she writes of her father’s absence throughout her coming-of-age in tender, genre-bending poems. July Westhale and Arisa White, former teaching colleagues and Bay Area community, approached this interview in an epistolary way, discussing form, family, voice, and taking up space on the page.

Translation: “Soy Nobody” by Emily Dickinson

Poem by EMILY DICKINSON

Translated into Spanglish by ILAN STAVANS

Soy Nobody

Translation by Ilan Stavans

Soy Nobody! Quién eres tú?

Eres – Nobody – too?

Then somos pareja!

Silencio! lo anunciarán – you know!