I walked to my apartment in Kathmandu the day after the earthquake. From the news on my iPhone, I had seen that the palace squares had fallen. But when I left the tents where I had slept the night before, I found the flowerpots were still poised upright on the third-story windowsills and on the roof walls at the shop across the lane. The sidewalk had cracked along the water line. The garden walls had collapsed, and it was hot. But those flowers had not moved; they were as they had been. They caught the light. I had envied the plants. In the months I lived in Kathmandu, I had developed the impulse to notice them behind the dust I kicked up in the road as I passed them. That afternoon, there was not any dust because there was no traffic, not even a motorbike, although my landlord had taken her scooter out; she must have been buying emergency rice.

In Kathmandu, with money comes the right to fence a yard and cultivate a bit of nature against the city. That was what was done there. I lived around large houses on old streets that led towards a wide washing pool, dhobi ghat. The plants grow wild and thick behind high metal gates there. Some plots have lawns. They grow palm-width lilies, bowl-shaped pomelos, ottoman-sized succulents, and ladder-tall banana leaves in the cut grass. They were little oases, while the nearby roads were harsh realities.

The Yale Environmental Index, which ranks countries according to air quality, foundNepal has the second most polluted air in the world, after Bangladesh. The World Health Organization standard for bad but livable air is 25 micrograms per cubic meter; at rush hour in Kathmandu, it was 20 times that. Before the earthquake, I had written about that crisis. Then, it was slow; it was normal. Now, post-quake, it is irrelevant. I am no longer in Kathmandu. I watch a cut-up of relief posts, news stories and videos on Facebook of affected districts, areas where the landslide risk is now high because of monsoon. No one mentions the air.

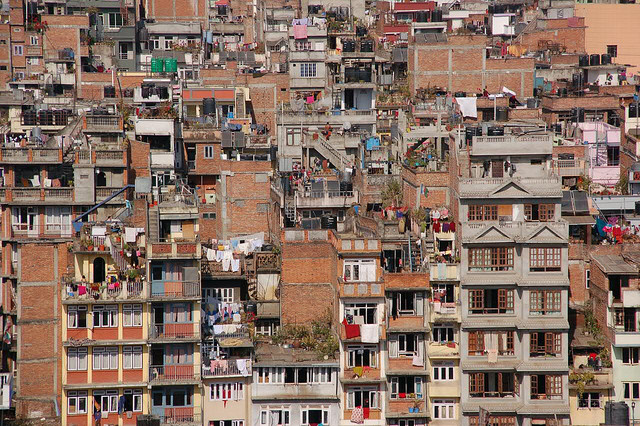

But this what I wrote and how I remember daytime before the distaster: hot thick soot mingling between the open metal tuk-tuks and motorcycle helmets, stalled in traffic. The relief was in moving—in getting to where you were going and away from the road. There are too many scooters, motorbikes, and cars for the small valley. Since democracy began in 1990, millions resettled from hills or from the plains and now wait for the constitution promised to them after the civil war’s ceasefire in 2006. There is still no constitution, and public planning is papery at best. It was necessary to put some energy into assembling do-it-yourself infrastructure at home, municipal systems for heating and electricity being thin to non-existent.

The house I lived in was concrete, like many in Kathmandu, built to be cool in summer and cold in winter; there was no heat. In winter we boiled water on a gas stove and sat by halogen lamps or gas heaters to keep warm. Halogen had drawbacks: it could only operate on full electricity and for 11 hours a day because each area of the city had a schedule on which its electricity would be cut (a schedule I followed with the app on my iPhone), euphemistically called loadshedding. We used an inverter battery, common household fixtures for those who could afford them, to charge cell phones and laptops or put on a low-watt bulb. Gas had drawbacks too: being expensive and being scarce. The papers speculated in January that producers kept supplies low to push prices higher. At least the solar heater supplied hot water freely so long as the sun shone. I had envied the plants for keeping solar panels under their skin, thriving even as they did not move, blossoming in their fenced-in lonely gardens, better than on the roads.

I used to live on the far south side of Kathmandu, and if I was crossing the river and going into the middle heart of the north bank for a research appointment, I would lean on my mountain bike and pedal on the yellow road margin, displaced by the cars and motorcycles next to me. I used to go faster than I thought I could, my cyborg frame keeping pace with Suzuki and Tata engines, but the company was dangerous: turning vans, a ladder-saddled rickshaw driver, squads of teenagers in school navy uniforms rolling deep into the street. “Crowded,” interviewees used to say when making small talk with me about the city, pointing out a car or office window near the road. It was a complaint veiled as fact; the point was not overpopulation but that there were people working against you, making your path through the city loud and cramped—chaos that would be too much even if it wasn’t almost everywhere, although it was.

I suspected I felt the strain more because I was new to the city. After I would park my bike somewhere, I would take off my helmet and press my palms over my eyes and cheeks and forehead to undo the knots my face had made while trying and failing to steel myself while I had been riding. But I began to notice other vulnerable bodies on the road—during the spring wedding season, a lipsticked woman picking up her sari skirts looking both ways anxiously on a thin median, elderly friends and couples almost holding hands as they cross a six-lane highway, as if together they could physically resist the oncoming traffic.

Some days I took the public microbuses to get across town, and the boys operating the routes insisted on fitting as many travelers as they could into the vehicle. Sometimes I would hang on the inside railing of the open van door. Once I curled so small that my head was upside down, seeing the road pass between my legs, easier than trying to stand half-upright. With room, I would exchange ameliorating smiles with the women in the car. They debated like highway Californians about where to exit, where to connect. The wrinkled ones would sling snide jokes to all of us in earshot. I remember one pointedly raising an eyebrow at the men sitting comfortably at the back as we, near the door, were piled onto. It was good to share the ride. Having capacity to navigate Kathmandu alone was unrealistic.

In fact, at moments, it was a fantasy. One day in January I went to the movies downtown, near Sundhara, the main depot for the microbuses and the site of one of the few CCTV videos of the earthquake. I remember the previews: high-speed broadband, shampoo, a candy bar, and a high-rise apartment complex. There was also an ad, high-production value, for a Yamaha FZ Series 2.0 motorcycle. I usually feel old watching commercials in South Asia, seeing a line of companies whose promises seem like worn American classics run through a loophole, their products guaranteeing good beautiful mothers and sports trophies with each purchase of a washing machine or wheat cereal. But the Yamaha got me. In the ad, Bollywood model John Abraham’s thick arms become metal, then his whole body does. He dons a helmet and becomes his bike, driving through a dark video game cityscape and highlighting the features of the bike before stopping, now flesh and blood, but with an x-ray-shown heart, a steel engine. The tag line is, “It’s not a machine—it’s me,” but the point is the opposite. He is both man and machine. I wanted to be like that—as solid as my bike frame, able to bear weight and withstand crashes, to be immune to pain and scrapes and instead be designed for precisely my purpose, for this city.

There was action to take about the air, but I did not take it. I could have worn a mask. At old Baneshwor chowk I saw hipsters wear them low and stretched from nose to chin like bandits. On the bus, parents who have not put one on themselves have outfitted their children. The masks sold on street corners at shops with candy and cigarettes. They are cotton and said to do nothing. Do I get one? The argument I hear is that they don’t matter; the counterpoint is that at least they do something. The decisive thing would be to buy a disposable respirator, which covers your nose and mouth with two ventilators through which to breathe, your very own little atmosphere. But someone once had described to me how, over time, you see their filters turn black. What is really required in Kathmandu is to accept that the best your body can do against the city is definitely not enough. Because you are damageable, you need the machine.

“Unlivable” was the word that The Guardian used about the air, even though people do, of course, live in it. For the word to make much sense depended on dark predictions about the future. Now post-quake, “unlivable” is about the present, used for buildings whose walls and roofs the disaster made structurally unsound. That context has made “unlivable” seem misapplied when referring to bad air. But still, for me the word had captured what it had been like to live in a city that could make me feel, however distantly, that as I watched that Yamaha ad it was not enough to have just tissue lungs and bone skeleton in order to survive.

When we talk about crisis we mean big malfunctions and we mean systemic breakdowns. We mean that something broke, even if we do not know exactly what and suspect it was likely too many things to count. I got off the tarmac at Tribhuvan International and the air pollution was undeniably present, even from the airplane steps, but within a day or two I could no longer detect it. It made the scale of the pollution easier to forget about, and that felt like a malfunction on my part, another breakdown among many.

By definition, crises have turning points: malfunctions that begin them, and remedies or catastrophes that end them. With the second worst air on the planet, by one count, Kathmandu pollution should have been a crisis, but it had no discernable start and certainly no definite end. I used to wait for the moment I could tell I was losing breath from smoke faster than I had been gaining stamina to bike. I was waiting for a turning point, an occasion to act. It never came. I found a 3M disposable mask with a filter overseas and brought it back to Kathmandu but barely wore it. Its thick paper was hard to breathe through, harder than breathing through smog. I stopped trying to reason through unreasonable situations, finding my logic wanting regardless.

“Unlivable” is a climate-change era neologism, describing the present world we live in by forcing the impeding future to reside here, in the way we talk about now. It insists that we will become hobbled anatomies against our hopes that we won’t. It also instantiates a wider truth. When it comes to disasters, the ends and beginnings that crises want to shape out of disasters never really exist.

The Nepali government described the earthquake as a crisis. After imposing a state of emergency following the quake, it began to rush the constitution-making process undemocratically. In the past few weeks regional protests in response have spiraled and become deadly. The politics are happening on an acute timeframe, but their end is elusive. Similarly, though the earthquake itself happened so fast, the rebuilding that is happening across the affected areas is gradual, incremental. The aftermath is beyond crisis. As disaster, the earthquake has gone on long after the aftershocks subsided, as well as the supposed end-point that international news crews implied was reached when they departed many months ago.

Sahiba Gill served as an assistant editor at The Common. She is currently a student at New York University School of Law.

Correction notice: When this essay first aired on September 4, the regional protests mentioned in the final paragraph had not been mentioned. The essay has since been edited to acknowledge these protests.

Photo 1 by Flickr Creative Commons user Oliphant

Photo 2 by Flickr Creative Commons user ~zipporah~