S. TREMAINE NELSON interviews GREGORY RABASSA

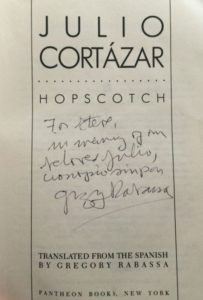

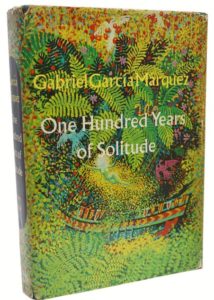

Gregory Rabassa is a genius you might pass on the streets of New York City without even knowing it. Born in 1922, he lived the early years of his life in Yonkers, New York before moving to a farm near Hanover, New Hampshire, four miles from Dartmouth College, where he studied as an undergraduate. In 1967, in his very first attempt at translation, Gregory Rabassa won the National Book Award for his translation of Julio Cortázar’s novel Rayuela (Hopscotch in English). Rabassa’s translation schedule filled up, and, in his own words, he was “too busy” with other projects when Gabriel García Márquez approached him about translating Cien Años de Soledad. At Cortázar’s urging, García Márquez agreed to wait three years until Rabassa’s schedule cleared. Upon the publication of One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1970, García Márquez famously declared that Rabassa’s English version of his book was better than the Spanish original.

Gregory Rabassa does not own a computer or an answering machine, so getting in touch with him took time. S. Tremaine Nelson called on a weekday at 11:00 a.m. and no one picked up. He tried a few days later at 3:00 p.m. and again no luck. On the third attempt, he called at the conspicuously early hour of 9:00 a.m. and Professor Rabassa answered the phone, coughing an abrupt “hello?” Startled, S. introduced himself and hastily explained that he was a fan of Rabassa’s work, simultaneously realizing how insane it sounded, that a fan of his work would be calling him in the privacy of his own home, at 9:00 a.m. no less, out of nowhere, and yet Rabassa listened graciously, perhaps found the nature of the phone call amusing, and agreed to meet for lunch near his apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

S. Tremaine Nelson (SN): How is your health these days?

Gregory Rabassa (GR): I feel the way I felt when I was 20 years old, but when I was 20 years old I was carrying a 50-pound pack, a 10-pound rifle, 5 pounds of ammo, and slogging through the mud in World War Two. And that’s the way I feel.

SN: So do you still get around the city much?

GR: I’m slowing down.

SN: Is your wife Clementine also a New York City native?

GR: Yes, she was born in Hell’s Kitchen, where my mother was born.

SN: How long have you been married?

GR: 45 years. I had just moved from Columbia to Queens College, doubled my salary. That was the strange thing back then. The public institutions were out-paying the private. Then the public schools stagnated, and the private schools were paying more.

SN: How has New York changed in the time that you’ve lived here?

GR: I miss some of the things that have been torn down.

SN: Such as?

GR: The Polo Grounds. The Third Avenue El.

SN: Second Avenue Line is coming any day now.

GR: Right. [Laughter]. Any day now. I read about the noise in the local papers. The explosions. We’re too far down here to hear them, but I suppose it’ll get louder and louder. You know, the Village has changed, too. It’s become like here [on the Upper East Side]. In my day, you know, it was the Village. You’d walk out and see somebody you’d know on the street. Friends would sit outside their apartments and so-and-so would walk by and you’d say hello.

SN: You’ve come in contact with an amazing variety of people.

GR: My favorite poet was Dylan Thomas. Had his last night at the White Horse Tavern. I used to drink with him at the San Remo down on Bleecker.

SN: There’s a painting of him in the White Horse Tavern.

GR: By my standards for the Village, that was a long way away from where I lived on Morton Street.

SN: What were some of your other favorite spots?

GR: One or two are still going. Minetta’s. Chumley’s. I heard it blew up, though. I haven’t been back to Chumley’s for years. We used to go there all the time. They never changed it. Mrs. Chumley herself was there after the war, she’d sit there in the corner, nursing a beer.

SN: Any authors you expected to last that haven’t maintained their reputation?

GR: Cortazár has become a scholar’s author. He’s the one who was the most fun.

SN: Should readers read Hopscotch back and forth or right through?

GR: No, read it right through. Then read it the other way, and it’ll be a different book. That’s the way he meant it.

SN: You and Julio Cortazár shared a love of jazz. What’s the best jazz performance you’ve ever seen?

GR: Well, that goes way back to my college days at Dartmouth. We used to hitchhike down to the city and go to 52nd Street, and of course that’s where I saw Billie Holiday.

SN: Where was she singing?

GR: She was in various spots, the Open Door, Onyx club, the whole row of them there. She was one of a kind. You could tell she was special.

SN: You enlisted in 1942.

GR: Correct. I was six credits short of graduation. They gave me three points for Physical Education for my time in the infantry, and Modern European History for what we were doing at the moment.

SN: What branch of the military were you in?

GR: Office of Strategic Services.

SN: Is that still a part of the army?

GR: They call it the CIA now.

SN: Doing cryptography work in the war, were you ever involved in any interrogations of prisoners of war?

GR: Some.

SN: Care to elaborate?

GR: We had German prisoners. I was trying to study German, to help with the code cracking, but then Russia was invaded so I studied that instead.

SN: Do you have any good war stories?

GR: There’s the time I danced with Marlene Dietrich.

SN: Where did you dance with Marlene Dietrich?

GR: It was a private OSS ceremony in Algiers. She wasn’t wearing much because it was warm out. So I was sitting there, and she was dancing, and she said, ‘Sergeant, you’re not dancing,’ and she pulled me onto the dance floor.

SN: How did she dance?

GR: She danced very well [laughter].

SN: Clarice Lispector, whom you’ve translated, has been called the Marlene Dietrich of the literary world.

GR: I came up with that phrase. People didn’t like it, though. They said it was too damned chauvinist.

SN: Are you still in touch with your authors?

GR: Not many, some.

SN: When did you lose touch with Gabo?

GR: Quite a long time ago. I wasn’t that much in touch with him anyway. Julio and I were closer.

SN: Do you read any contemporary fiction?

GR: Not much new fiction. Right now, I’m reading Proust. Proust got me into this whole thing. Ramon Guthrie at Dartmouth, my professor, first introduced me to Proust. He was part of the Paris crowd. Ramon had quit prep school, came from a good Connecticut family. He went off to war in France, and of course when the Americans came he stayed in France on their version of the G.I. bill, went to French law school, married a French woman, who was a painter, and they hung out with Hemingway. When Hemingway’s son came to Dartmouth, Ramon remembered him from when he was a baby.

SN: So you read Proust with someone who had lived in Paris in the 1920s?

GR: He didn’t know Proust, but they were contemporaries.

SN: Did you read Proust in French originally?

GR: Of course!

SN: Which English translation do you recommend?

GR: Moncrieff’s all right. He was criticized for the title. Moncrieff’s gesture was to throw ‘Remembrance of Things Past’ into the title. People who criticized him read too frivolously, people who hadn’t read Shakespeare’s 30th sonnet, ‘When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past.’ If you read the rest of the sonnet, it’s a pocket version of Proust’s novel, and Moncrieff saw that. Ramon and Proust. That was what switched me from being a chemistry and physics major to being a language major.

SN: Any specific memories of first studying Proust in the classroom?

GR: Well, Proust based the structure of his novel on Beethoven’s 14th quartet, and Ramon would play his music.

SN: But the novel’s so long.

GR: Well, music condenses. Tchaikovsky’s 1812 overture, for instance.

SN: A former professor of mine at Vanderbilt, John Halperin, once told me not to read Proust until after I was 30. Is this good advice?

GR: He got that from [José] Ortega [y Gasset], who said anything you do before you’re 30 is no good. Between 30 and 40, those are your years. You get to be 40 you’re too goddamned old. No. I don’t know. Not sure how much age has to do with it. More experience. Think of Rimbaud. He was 19 or something, started writing when he was 16 or 17, not educated in the modern sense of the word. Of course he never wrote a novel, but maybe poetry is different.

SN: Why should any young artist consider translation as his métier?

GR: He shouldn’t [laughter]. If you’re going to do it, do it the way I did which was with no intent of doing it. It was there, and I did it. To take it on seriously, they don’t do it right. They get involved in linguistics, which is a totally different field.

SN: What is the overlap between linguistics and translation?

GR: Dialect, dialectology, the reason one word takes the place of another. Theories, you know. Translation is more like acting. You become the author. You’re writing his novel in English. And you have to know what he’s doing. When you do Hamlet, you become Hamlet.

SN: Do you consider the translator an artist?

GR: I think so. If he’s good he’s an artist. That’s why you can’t teach translation. You can teach a craft, but you can’t teach an art. You could teach Picasso how to mix his paints, but you couldn’t teach him how to paint his Demoiselles.

SN: I was wondering if you could share your thoughts about different translations of the Bible. Should it be approached differently?

GR: The Bible is a very good study of translation.

SN: How so?

GR: Because the translations were all from different periods. Some classics are similar, but not as much as the Bible because it comes from so many different languages. It starts off Hebrew, Aramaic, then it becomes Greek, Latin, vernacular.

SN: Can you talk about the infamous “camel passing through the eye of a needle” Bible verse?

GR: That was a street in Jerusalem, a narrow alley called the Eye of the Needle, like Minetta Lane. Camels had trouble going down that narrow street.

SN: And yet somehow the translation still communicates the message?

GR: Right. Translation is also a simile, a metaphor. The way that vino is a metaphor for wine.

SN: You mean in the relationship between the signifier and the signified. Have you read Derrida extensively?

GR: He’s fun to read, but I think he’s full of shit. The French are scholastics. It’s strange that they threw out the Jesuits when they’re so damned Jesuitical.

SN: Were you raised in a religious home?

GR: No. My father, as a Cuban, was Catholic and he insisted that we went to church, but up in New Hampshire, my mother, whom he converted, took us. He said he would prefer to say his mass by the radio because back then he could get the Montreal symphony. I started to doubt religion when I found out you could lie in confession.

SN: What, in your experience, is the effect of religion on art?

GR: I don’t know that it’s so much religion, as much as each person’s sense of religion, his personal interpretation of it. As to having a religion, I don’t know. If García Márquez had any religion it might’ve been sentimental. I don’t think Cortazár did. In Julio’s case it was intellectual. He knew his religion, but he didn’t believe anything. Gabo would have believed in something in some mystical sort of way. I don’t know that any of them had any orthodoxy.

SN: What is your oldest memory?

GR: I remember Yonkers. My continuous memory started coming up in New Hampshire. If I had the power to recall, I could remember that moment, before I was ten years old, of the house in New Hampshire.

SN: I was wondering if you could talk about trying to find the perfect word for moonshine.

GR: I think I used rot-gut. I remember that from my childhood days. There are a variety of words in Spanish, depending on the country. In Portuguese I know it better. Cachaça. But then they have a word in Portuguese ‘pinga’ [that] means drink, because pingar in Portuguese is to drip. García Márquez would have used aguardiente. In Spain that means brandy, like cognac, but aguardiente in the Caribbean—that would be cane liquor. Caña. That would correspond to corn liquor.

SN: Do you have any advice for young writers?

GR: Make it sing. A fiction writer should read a lot of poetry and vice-versa. Young writers should study Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Faulkner. Faulkner had rhythm. Of the foreigners, there’s only Proust. Moncrieff gets a hard time, but he’s good enough.

SN: Have you ever attended the Nobel Prize ceremonies in Sweden?

GR: No, I got my prize in 1942 when I danced with Marlene Dietrich.

SN: Are there poets you still read today?

GR: On and off. Catullus in Latin, with the help of the dictionary.

SN: Why read Latin poetry today?

GR: Because it’s good.

SN: What advice would you give to young poets?

GR: Don’t lose faith. Do as you will.

Gregory Rabassa has translated many South American giants of literature, including Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez, and Clarice Lispector. He is the author of the memoir ‘If this be Treason:’ Translation and Its Dyscontents.

S. Tremaine Nelson is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and founder of The Literary Man book blog.

Photo credits: Headshot of Gregory Rabassa copyright E. Fricke Nelson; Cover of 100 Years of Solitude copyright RareBooksFirst.com; Image of Gregory Rabassa inscription in Julio Cortázar copyright S. Tremaine Nelson.