This is the first part of a two-part Dispatch. Pt. 2 will be published online in November.

*

She slept for the first two hours of the trip, and when she woke up, the first thing she said was, “When we get back I want a divorce.” We were headed north with the hopes of going to Canada for no other reason than to say that we’d left the country. We’d decided on Thunder Bay, Ontario, because it was the closest destination across the border from our home in southern Illinois. And now, it seemed, the trip was doomed before we’d covered half the length of our own state.

I can’t remember why Catricia wanted a divorce, though there are other moments in our relationship that I remember why all too clearly. In those days we were tempest-tossed in the constant struggle of being in love with each other and fearing the loss of our individual selves. We’d gotten married so young, had thought it was just a piece of paper to appease parental harassment about living in sin, as if signing a legal document could suddenly change something from sinful to holy, but we hadn’t understood how easily we would slip into the roles we’d been groomed for our whole lives, how difficult it would be to fight against small town Midwestern attitudes about what a marriage should look like. But by the time we hit the Wisconsin border four hours later, we’d come into a sense of mutual peace. Roving far from home and entering into new places together always brought calm into our lives.

As we traveled north into the Dells, the landscape changed from flat prairie to rolling hills set with red barns and farmhouses with stone foundations — and yes, black-and-white dairy cows. It was like driving through the pictures of farms drawn in children’s books. Perfect and simple. The highway curved around long glacial lakes with old resorts that had been retreats for generations of Chicago families, and I remembered something I’d read recently about a cabin that had been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright being discovered nearby, left to rot into the scenery.

We turned at Eau Claire into the north woods, headed for our first overnight stop in Duluth, when a knocking came from the beneath the car’s hood, loud enough to be heard over the stereo. The same as our young marriage, our car didn’t seem to fit us either — a 1987 Cadillac Sedan de Ville, white with burgundy interior. It had belonged to the city commissioner in the town where Catricia had grown up, and when he put it up for sale, Catricia’s grandfather, who was a mechanic, said it was a good deal. Her parents agreed, talking about the roomy interior and easy ride, as if we were 62 instead of 22. We bought it, and called it the “Fatty Caddie”.

So there we were, a day’s drive from home in the middle of nowhere, with the clacking getting louder. It sped and slowed with the engine, and we pulled over and popped the hood. I wrapped a shop towel around my hand and held it against the alternator casing while the car idled, feeling the beat of metal on metal. The bearings were going out. This was before cell phones (unless you count those phones that people carried in small duffle bags, but we didn’t have one of those either) and there were no houses anywhere nearby, so we decided to make a run for Duluth.

We drove easy, listening to music, talking about the scenery, trying to ignore the banging from the alternator growing louder. When we arrived in Superior, a town just across the lake from Duluth, we went to our hotel and found an alternator shop in the yellow pages. They were open for another 45 minutes, so we hurried across town, sounding like some kind of steam-powered contraption, and arrived in time to buy a rebuilt GM alternator for 167 dollars, which I put on our credit card — the one I’d gotten my second year in college by filling out an application at a folding table outside the student center. (They were giving away free tee shirts.)

When you grow up in a family that drives used cars, you never travel without tools, and this trip was no different. We opened the hood one more time, and I changed out the alternators in the parking lot, taking the old one into the shop just as they were closing in order to recoup the core charge. The workers smiled at us and told us to have a good trip, probably wondering what the hell two kids were doing driving to Thunder Bay in an old Cadillac, but we didn’t care what anyone thought. We had started the day at the brink of divorce, driven 150 miles with a failing alternator, repaired the alternator in a gravel parking lot with a set of tools from Sears, and now we were on our way back to the hotel, the engine humming smooth like a sewing machine.

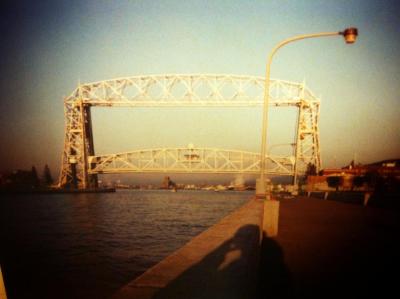

We showered and drove across the bridge into Duluth for supper. The city was like nothing we’d ever seen — mist gathered among the trees and houses and buildings tucked into the hillside above the lake. Downtown, we walked among crowds along the waterfront, shivering because we hadn’t thought to bring a coat in June. We ate in a pub, and afterwards drove higher into the city, the streets going from the flats next to the lake at a sharp grade up the hill. It was finally dark, the sun having set much later than we were used to, even on summer nights — our first experience of the effects of latitude — and steam rising from manhole covers shone orange in the streetlights. When we turned around to go back down, we could see a thin line of lights streaming from the city across the aerial lift bridge as cars made their way across the blackness that was the largest freshwater lake in the world. It was a spectacular sight. And the next day we would travel on into another country. But in that moment, we simply wanted to sit high above everything, looking across the darkness at where we’d been.

*

James Alan Gill holds an MFA from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, and this is his eighth dispatch for The Common.

Photo: Duluth Aerial Lift Bridge, 1997, by James A. Gill