Poems by IGOR BARRETO

Translated from Spanish by ROWENA HILL

These poems will appear in a forthcoming edition titled The Blind Plain, published by Tavern Books.

Los Llanos, Venezuela

Nature of Exile

(Apartment nocturne, 1998)

Some cattle arrived from a yearning for woods,

from some sorely missed hills.

What was the meaning of those animals

with their human faces?

The kitchen was a bonfire

at midnight.

The vegetable

hush of the balcony

where some ferns

flutter like sphinx moths.

What happened to the quiet of those places

I knew so well?

I didn’t find patterned mire

nor the blue shirt.

It was the nature of exile,

a river of nothing.

Something that cuts an onion in small pieces,

white, like a street lamp under a withered tree.

Naturaleza Del Exilio

(Nocturno de apartamento, 1998)

Unas reses llegaron del boscoso anhelo,

de unas calcetas añoradas.

¿Qué sentido tenían aquellos animales

de rostros humanos?

La cocina era una hoguera

a medianoche.

El acallamiento

vegetal del balcón

donde unos helechos

aletean como esfíngidos.

¿Qué fue de la quietud de esos parajes

que conocía tanto?

No encontré barriales constelados,

ni la camisa azul.

Era la naturaleza del exilio,

un río de nada.

Algo que corta una cebolla en pequeños trozos,

blanca, como un farol bajo un árbol marchito.

Mary

From an early age I wanted to have horses.

Then, I lived in a modest residential area

on a dirt road

to the east between Pennsylvania

and New Jersey.

I remember the sheriff’s rounds

in his metallic black Dodge,

the little gardens

of fleshy petunias

and the lawns

immaculately alone.

Oh, woods and lakes of Medford,

if it wasn’t for you

what would I have done

with myself.

I would never have worn the jacket

and the tightly strung

whip

of the learner rider.

My teacher was a German called

William Locklear,

an old man who loved

the poems of Heine

and scolded me

for my lack of balance in the piaffe.

That was my only fault:

I cleaned stables,

I discovered the misty steam

that horses give off

when they’re bathed,

and the patience to oil harness.

But my fate was in a different place

like an apple that changes a wicker basket

for the pocket of a traveler in a train

and then a ship

and finally a country of tree ferns

called Venezuela.

A country with the shape of a blood stain.

I often remember

the sun on the pastures,

the ribbed clouds of summer

and the campanulas

with their half-mourning mauve flowers.

That Arab filly with the sorrel coat

grazing near the house

at the end of a harsh day.

I can’t forget the children I had,

their clothes perched on the bushes

like white doves.

They say that hope calls at a door

that always opens,

but as the years pass

a horse catches up to itself

on its own legs,

treading on itself,

and that’s what happens to us too

because death dreams of beautiful things.

Mary

De muy joven deseaba tener caballos.

Entonces, vivía en una modesta urbanización

por un camino de tierra

al oriente entre Pennsylvania

y New Jersey.

Recuerdo la ronda del alguacil

en su Dodge de pintura metalizada,

los jardincillos

de carnosas petunias

y los patios de grama

inmaculadamente solos.

¡Oh! bosques y lagos de Medford Lakes

si no fuera por ustedes

qué hubiera hecho

yo de mí.

Nunca hubiese vestido la casaca

y el fuete

tensado con fuerza

de la aprendiz de equitación.

Mi maestro era un alemán llamado

William Locklear,

un hombre anciano que amaba

los versos de Heine

y me reprendía

por mi falta de equilibrio en el piafé.

Esa fue mi única culpa:

limpié caballerizas,

descubrí el vaho de vapor

que los caballos

despiden al bañarlos

y la paciencia de untar con aceite los aperos.

Pero mi suerte estaba en otro lugar

como una manzana que cambia la cesta de mimbre

por el bolsillo del viajero en un tren

y luego un barco

y al final un país de helechos arborescentes

llamado Venezuela.

Un país con la forma de una mancha de sangre.

A menudo recuerdo

el sol de los potreros,

los cirros estriados del verano

y las campánulas

con flores lilas de medio luto.

Aquella potranca árabe de piel castaña

pastando cerca de la casa

al término de un día inclemente.

No puedo olvidar los hijos que tuve,

sus ropas posadas en los arbustos

como palomas blancas.

Dicen que la esperanza llama a una puerta

que siempre se abre,

pero al paso de los años

un caballo se alcanza

con sus propias patas,

pisándose él mismo,

así también le ocurre a uno

porque la muerte sueña con cosas bellas.

Igor Barreto was born in San Fernando de Apure, Venezuela in 1952. He is a poet and leader of literature workshops. He has published ten books of poems, the latest entitled El Muro de Mandelshtam (Editorial Bartleby, 2017, Spain). In 2008 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. Several anthologies of his work have been published: Tierranegra (Ediciones Idea, 2008, Tenerife-Spain), Terranera (Rafaelli Editore, 2010, Italy), El campo / El ascensor (Complete works. Editorial Pre-textos, 2014, Spain).

Rowena Hill was born in England in 1938. She taught English Literature at the Universidad de Los Andes in Mérida, Venezuela, where she has lived for over forty years. She has published five books of poems in Spanish, and has translated into English some of Venezuela’s best known poets, including Rafael Cadenas and Eugenio Montejo, as well as an anthology of Venezuelan women poets.

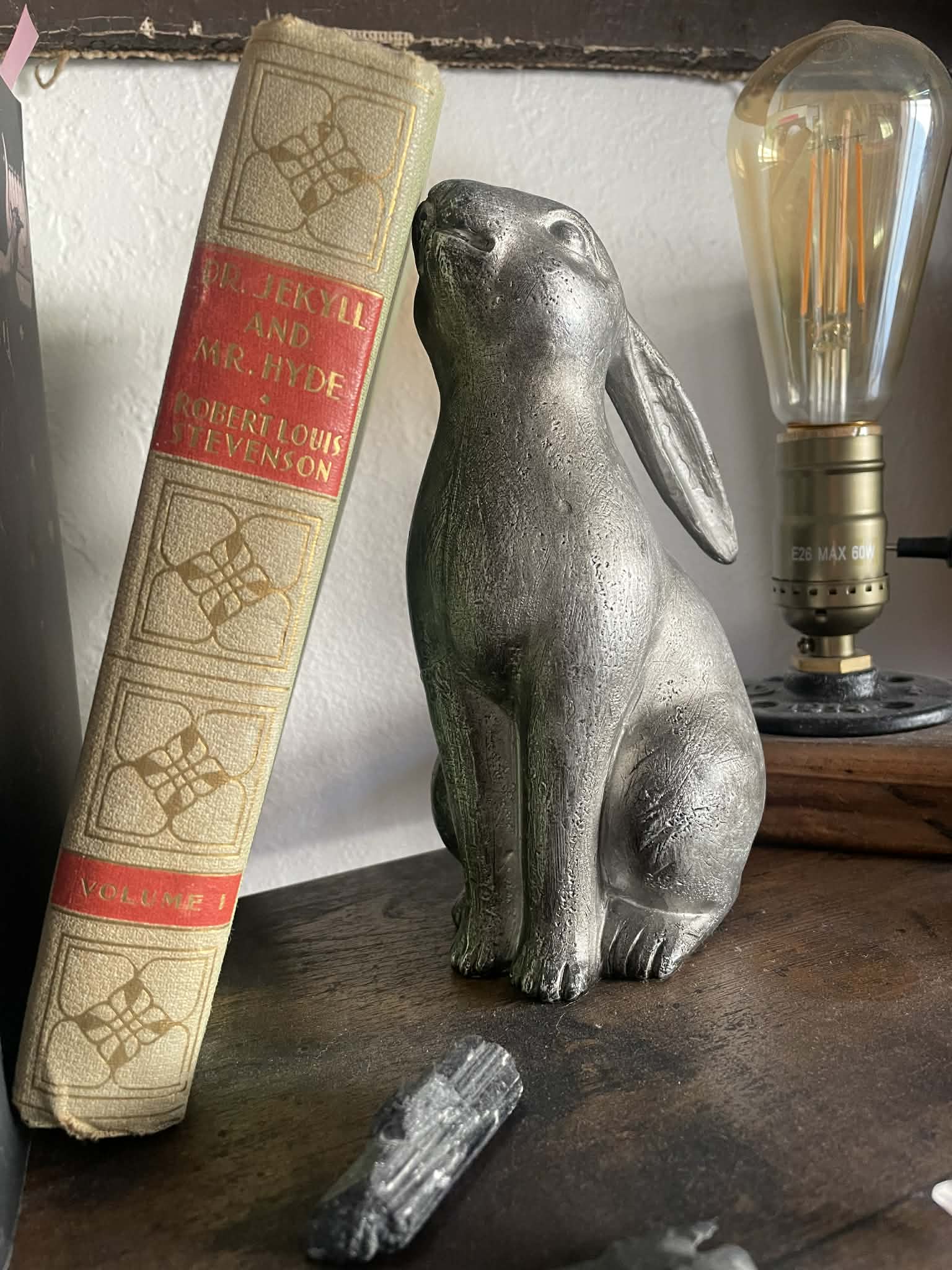

Photo by Flickr Creative Commons user Peter Fenda.