By MIK AWAKE

1.

I am walking my dog in the park when I see it, a caution display, one of many placed throughout New York on a given day, warning of bridge closures, flooded roads, construction ahead. I do not recognize it as art. At the end of the leash, Chester snouts the grass for discarded crusts of pizza folded like wings. VOTE ECO-LOGICALLY. I read before I know I am reading. FOSSIL FUELING INEQUALITY. It cycles through a handful of charged puns and a few phrases in Chinese, which I cannot read. I recognize in the wordplay a mind behind the messages. The display feels alive. 50,000,000 CLIMATE REFUGEES. As surprising is the strange comfort it gives. Where I expected the aloof drone of the State, I feel a consciousness. Maybe I am not as alone as I think; someone else is silently watching this planet die, too. Like many, I carry the helpless sorrow and guilt-ridden dread of a daily existence reliant on the exploitation of humans and fossil fuels, in a place made unimaginably wealthy off said reliance, watching year after year as more of my species flee homes made uninhabitable by said reliance. Like many, I have lived with this sorrow and dread for so long that it is as invisible as air, as quiet as my heartbeat, and as present. I take out my phone and add this and a few other photos to my camera roll. Probably, I would have forgotten about it, and a year later, on a data purge, I might have wondered, “What was the deal with that sign?” But you do not give me a chance to forget.

2.

On Twitter, where I am one of your followers, you tweet a thread of three photos showing a caution display like the one I saw earlier that week. Off Twitter, I happen to be teaching your essay, “Know Your Rights!” a singular tapestry of personal essay, reportage, and photography on police violence murals in New York. “Though the style of each mural was distinct, the message was the same. Somebody loves you enough to try to keep you safe…” I use you as an example of art made with the everyday. Just a pen, paper, and iPhone, a reassurance to my night school students, many of whom work more than one job but struggle to afford books. I spend a late millennial’s moment of doubt pondering social media norms before I finally reply with one of my photos: “Sunset Park too!” Your response is swift: “I wonder who put them up?” A few minutes later, you answer: the displays are part of Justin Guariglia’s “Climate Signals” project. There are ten throughout the city. “I think I’ll do the whole circuit,” you say after a few minutes. “Let me know if you want to do it with me.” A notification alerts me that, now, we follow each other.

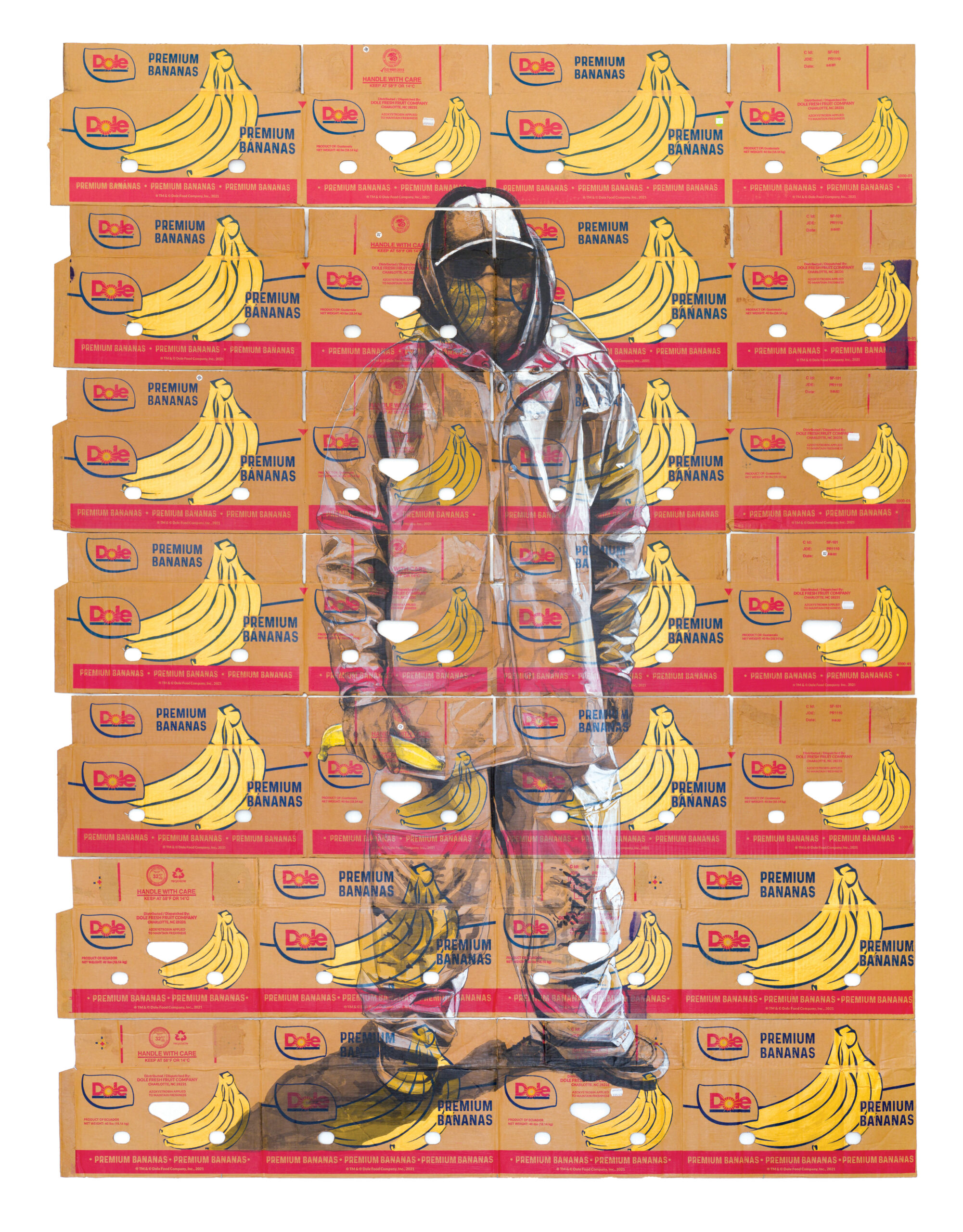

You tell me that you will be wearing a black backpack. I do not do things like this: meet strangers from the Internet at piers on the Hudson River in the middle of the day. We spot each other, shake hands, grab a table in the shade. We talk. The wind off the river has a chill. My knees bounce as I hear myself call myself a fan of your work. Your jaw shivers as you tell me about your son, who was obsessed for a time with weather disasters. There is worry etched on your face as you look out towards New Jersey, where you grew up. I sense that this worry is not only for your son, but for the proximity of a child’s obsessions to prophecy. We take our first photos of each other in front of the display. You wear sunglasses, I squint against the sun, having misplaced my clip-ons. No one seems to care. How few people even seem to notice the signals, in a way, becomes a meta part of the installation, part of its sad power. A middle-aged couple seem on the verge of engaging us in small talk, but something stops them. As you walk down the pier to pose for this photo, a group of high schoolers playing hooky ask you to settle a bet: isn’t the water in the ocean salty?

“Waiting at the foot of the stairs under the elevated tracks in front of Citifield.” Our texts make us seem like characters in a spy novel, or gangsters in a movie drug deal about to go left. What I really mean is this weekly pilgrimage with you, this step outside the known solitary into the unknown shared, the private into the public, is so outside my pattern of behavior—dog walks, Twitter, night class, subway, Twitter, groceries, Netflix, Twitter, therapy—so foreign to the way I have lived until now, that I imagine I am, in my small way, modeling the rupture of status quo required at scale to thwart disaster. In the handful of weeks it will take us to visit all ten of Guariglia’s signals, braving downpours and an unhealthy subway, visiting parts of the city we have never seen, I think about how, before this, we were living in the same city, and how, now, it is no longer the same city, as much because of our friendship as a result of all we have seen in search of these climate signs. And I think about how lonely it can be in this city, how lonely I was when I first moved from Georgia, before I found friends and love and community, and how ancient the desire is to exist so close to one another, a desire as old as God, such that even loneliness in a city like ours can feel like a gift, especially when that loneliness is shared or transmuted into art. The rain starts as soon as we meet and grows monsoonish, so loud we can barely hear each other.

It is Halloween. The 6 train is almost empty when I transfer at Bleecker to meet you in the Bronx. It fills with people dressed for work, but by 96th, it’s almost empty again, a snake digesting nurses, lawyers, welders, in which we see the outline of a city’s soul, its socioeconomic silhouette. I have only been to the Bronx twice before today and never for art. I am early. The streets are empty. I am hungry, but the bodega lacks the ingredients I want for a sandwich. Waiting for you, I watch a German Shepherd in a bee costume frolic in an otherwise empty dog run. The weather is perfect. When you arrive, you share your snack-sized container of hummus and crackers with me. The light in this photo is a chiaroscuro broken apart by the branches of the giant tree to your left. That’s one of the things I do now, as a result of the time I’ve spent with you: pay attention to the light in my photos. A streak of shadow on the hill behind you merges with your hair, creating the illusion of motion or a trail of smoke wafting towards the sign’s message (INEQUIDAD DE ENERGIA FOSIL), held in tension with your glance, lit with interest at two passersby, strangers to us, as we once were to each other.

“I think anyone who’s covered the issue would say pretty much the same thing. That you just feel like, ‘Well, I can’t—what else could I write about after this?’” I am listening to an interview with the science writer Elizabeth Kolbert on my way to meet you. Each week, from the last one in September to the first one in November, a new signal reaches us as we visit all ten installations. A terrifying United Nations climate report mandates a complete halt to the economic order. But nothing halts. Biblical fires swallow unbelievable swaths of California; the fossil-fueled President scoffs. I realize that I have felt so unconnected to these stories, that the notifications and headlines can often deepen the sense of helplessness, part of the rising alarm of climate fallout I have normalized as background noise. It cannot touch me and I cannot, here, safe in the house my wife and I have just bought, touch it. But the signs are piling, like extinction is the true city towards which we are being driven. I am thinking about the future of humanity while reading Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction and cannot help but recall Tomas Transtromer’s four-line poem, “Snow Is Falling”:

The funerals keep coming

more and more of them

like the traffic signs

as we approach a city.

Climate change is not scary in a way that we recognize as scary. The headlines repeat, only at higher frequencies, like an engine gathering speed. Another storm dons a person’s name. Harvey, Michael, Maria. There are no pegs or hooks, nothing new to grab in the rising tide of consequence. Alone on the subway platform heading home, a South Asian man exchanges pleasantries with a Latina woman selling churros and sliced mango. A smile, a shoulder squeeze. Nearby, a Jamaican busker does a karaoke version of Uncle Kracker’s “Drift Away.” This is what we will lose, I scrawl in my notebook. Our lives flitting across each other in the city, this place I have loved so madly for so long. I want to ask, What brings you here? What keeps you?

How the sun bore down on us on this stunningly arctic morning in Sunset Park, I could not capture a single decent photo of the sign’s text, a recurrent communication glitch between our lens and the LED message whenever the sun was overhead. This is the most legible shot I get, or at least I think it is, because I cannot read it anyway. I am fighting back depression, which the bad photos only deepen. There is nothing anyone can do about the sun. Its indifferent power a reminder why we have long conceived it a god. It seeks not vengeance for what has been done to earth, despite the appeal the idea may have that heaven considers us. The sun will survive my sadness. It will survive the economic order, even if our children do not. It does not care about our self-extinction. It cannot punish or propose legislation. It has no capacity to care about the unintended consequences of its existence. Before my wife and I moved deeper inland, we would walk Chester through the neighborhood’s utopian confluence of communities: Mexican, Chinese, and Yemeni children punting soccer balls across lawns overlooking the expanse of New York Harbor. Today, it feels like there is almost no one else in the park but us. Against the frigid surprise of the wind, you and I do not linger. Before we part ways for the week, you offer the sandwich you have made, our plan to have lunch in the park thwarted by weather. I am too sad to eat. “At least take the chips,” you urge. I take the chips, head upstairs and, for longer than I care to admit, I come undone, unraveled with loneliness. By the time I finally pull myself off of the couch, the sun has set outside. Chester is whining to be taken out. My wife is texting, wondering what we should do for dinner. I sit up and eat your chips in the dark. I don’t know.

Soon after I take the photo of you in Snug Harbor, an oasis I had not known existed, I discover an essay by the poet Patricia Spears Jones circulating on Twitter:

“If we find new ways to collaborate, circulate, create in our cultural production, we may begin advancing a different and more humane vision of a world where the struggles involve choices for the songs we want or need to sing, instead of self-annihilation or the destruction of children or our environment not even in the imagination…Social media is a tool and a resource — it cannot replace real-life community. We have privileged the conversations in social media over our own face to face communications. We should remember how important it is to meet and work together as is done within organizations when we use our time together as wisely as possible.”

I click the button meant to resemble a heart. In truth, there is no button for what I mean, which is: I met Spears Jones once in the lobby of the Museum of Modern Art. Both of us were early for a performance of the Lone Wolf Recital Corps, an experimental troupe founded by the late Terry Adkins, who passed away too young from heart failure. Poet Tyehimba Jess blew a harp beside novelist Arthur Flowers, who strummed an electric mbira, as artist Rashid Johnson loped slow circles in something like an executioner’s hood. Flowers called out Adkins’s name—a praise song, a conjuring. Only now am I making the connection between the Patricia I met in the lobby and the poet Patricia Spears Jones. That evening, I felt her sadness for the loss of Adkins and, in the shared attention we gave a series of photographs hanging near us in the lobby, felt also the quiet awakening that passes between strangers, two people looking at what another has made, separate, together, alive.

I have come to cherish these outings with you, already growing sad at their approaching end. I’m looking forward to meeting Emily’s kids, I put in my journal. I am told they will be in costume. They remain, months later, a ninja and scarecrow in my mind. In a moment of instant karma right before taking this, I plant my fair-trade, sustainable Veja sneakers in a huge pile of dog shit after bragging to you about them. You have every reason to laugh at me, but you do not. No, that is nowhere near your style. You disarm strangers with an unforced warmth. I start treating strangers this way, too. When your son hurts himself, leaping from a bench, we crouch by his side and you ask him where it hurts. “My elbow, my knee, my ankle,” he weeps. The next second, he is up and leaping benches again, as though naming one’s pain can be a spell for curing. As you encourage your son, you encourage me—to name the pain of life on the cliff’s edge of the Anthropocene, a space not unlike the margins upon which I often scribble and in which I live. Our friendship was forged in a somber treasure hunt across New York in search of Guariglia’s signals, but also in search of a meaning, or as you put it, “we were also stumbling together on a path toward new language, led by the signs.” In the soil of my despair for a racist economic order driven by fossil fuels, I nurture a new vision of the future and find it echoed in the bold, generational thinking of new legislators who will be elected to Congress tomorrow. When I get home, I go for a run, my first in a while and find a pair of ear buds in the pocket of my fleece that I assumed lost forever. This, then is the closest thing I have to wisdom: that the world opens itself to us only when we open ourselves to each other. We must use our time together as wisely as possible.

Photos are courtesy of the author, with permission from Justin Guariglia, The Climate Museum, and Emily Raboteau, who has written a companion essay to this one that appears in The New York Review of Books.

Mik Awake’s work has appeared in Popula, ArtNews Magazine, The Awl, and elsewhere. With Daniel R. Day, he is the co-author of Dapper Dan: Made in Harlem, forthcoming from Random House.

Join Mik, Justin Brice Guariglia, and Emily Raboteau at a conversation about the climate crisis and how we come to terms with it, presented by The New York Review of Books. The event is free and open to the public; seating is available on a first come, first served basis. Thursday, February 29, 7-9pm, at The Writers Room in New York City.