By MIK AWAKE

1.

By ADÁL

Introduction by Mercedes Trelles Hernández here.

Viviana García Meléndez Jumping Portrait, 2017

Text by FRANCISCO FONT-ACEVEDO

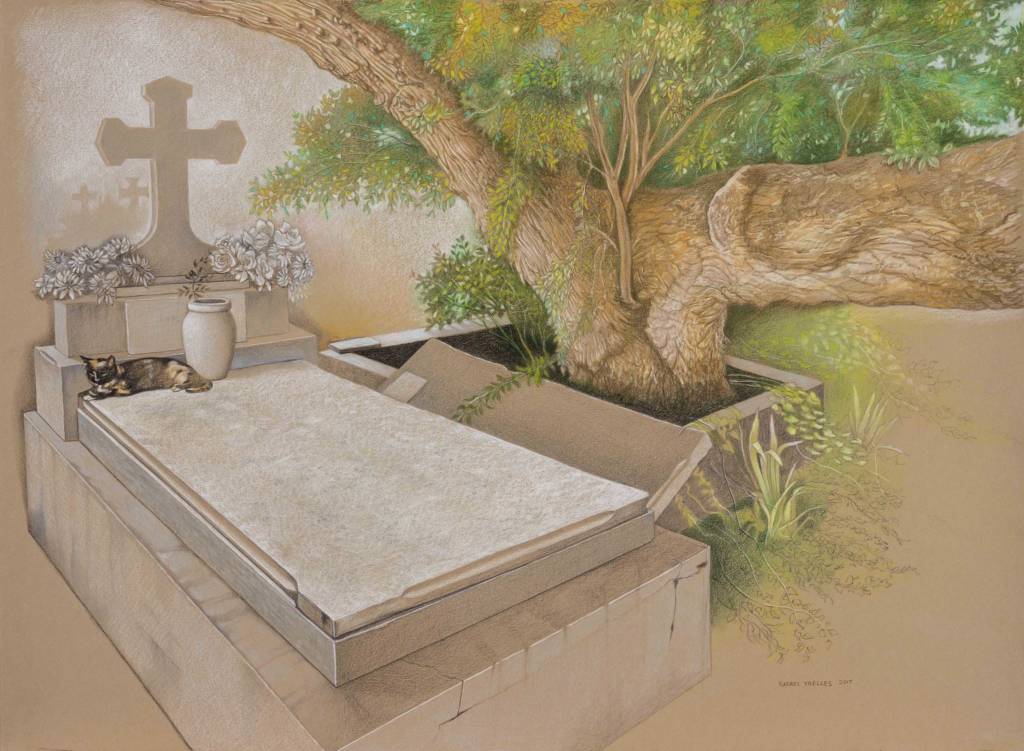

Images by RAFAEL TRELLES

Santurce, originalmente llamado Cangrejos, fue municipio desde el siglo XVIII, aunque luego fuera anexado como barrio de San Juan. Fue también el primer pueblo fundado por negros en Puerto Rico en 1773, cien años antes de la abolición de la esclavitud en el país. A partir de la construcción del trolley (primero a vapor en el último cuarto del siglo XIX, luego eléctrico a partir del 1901), se cambió el nombre de San Mateo de Cangrejos al de Santurce, en homenaje a Pablo Ubarri, Conde de Santurzi, encargado de la instalación del tren. Durante el siglo XX, en especial durante la modernización del país a partir de los años 40, Santurce se convirtió en el centro económico y cultural del país. Llegó a tener una población de 195,000 personas en 1950. Luego del proceso de suburbanización del país y la construcción de los centros comerciales a partir de finales de los años 60, la importancia de Santurce decayó notablemente. En la actualidad su población ronda los 82,000. Aun así, sigue siendo el barrio más poblado del país.

Los textos que siguen están narrados por Santurce/Cangrejos mismo. Las imágenes son de los murales tal como se reprodujeron e instalaron por todo el barrio. En todos los murales hay una imagen, un texto, el título del libro, un mapa y unas instrucciones para el peatón.

Para más información puedes ver nuestra página web: www.santurceunlibromural.com.

Although it was later annexed as a neighborhood of San Juan, Santurce—originally called Cangrejos—has been a municipality since the eighteenth century. It was also the first town founded by blacks in Puerto Rico, in 1773, one hundred years before the abolition of slavery in the country. Since the construction of the trolley (first the steam model in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, then the electric one in 1901), San Mateo de Cangrejos was renamed Santurce in homage to Pablo Ubarri, Count of Santurtzi, responsible for building the commuter railroad system. Throughout the twentieth century, particularly during the modernization of the country which began in the 1940s, Santurce became the island’s economic and cultural center, with a population of 195,000 people in 1950. After the suburbanization of the country and the construction of malls at the end of the 1960s, Santurce’s importance declined significantly. Its population now stands at approximately 82,000. Even so, it remains Puerto Rico’s most populous district.

The texts that follow are narrated by Santurce/Cangrejos itself. The images are of the murals just as they were reproduced and installed throughout the neighborhood. Each mural includes an image, a text, the title of the book, a map, and instructions for pedestrians.

For more information, visit our website: www.santurceunlibromural.com.

![]()

En Mis Brazos

En Mis Brazos

LOOKING FOR MY CITIZENSHIP

After Adál

When I am unsure of who I am

I pick up my dominos

and search out el reverendo

Pedro Pietri

so we can pray for clarity.

Years ago, I wrote that seekers of all stripes—journalists, philosophers, scientists, mystics—are chasing the same elusive thing: something like truth, understanding, a fully integrated perspective, awakeness, untangling. We just ask questions in different contexts, modalities, and microcosms.

Untitled from the Jane Doe Series

Untitled from the Jane Doe Series

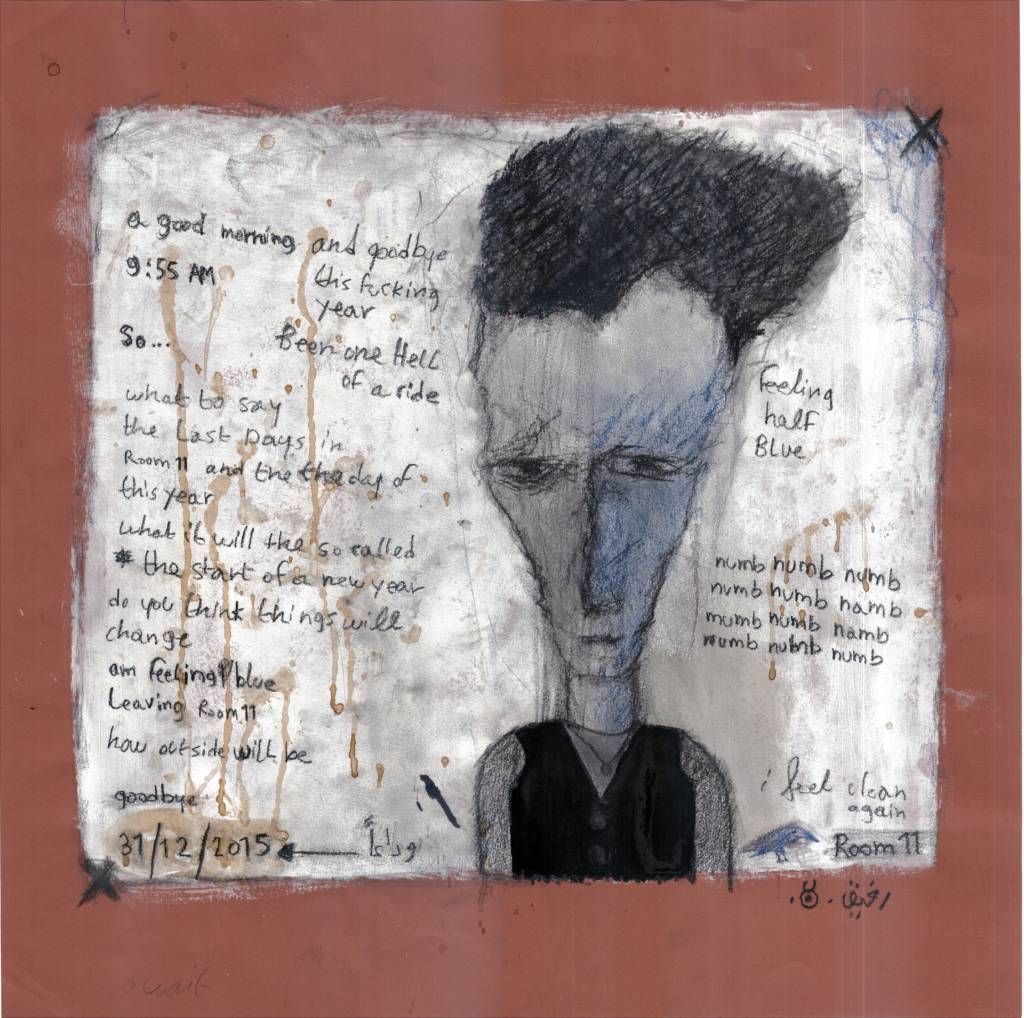

Untitled

From the Room 11 Series

Images by MARTHA ROSLER

Introduction by DARSIE ALEXANDER

Images by Michael Mazur and Betsey Garand

Three weeks ago, I had an intimate and frenzied encounter with a wild bobcat as it was chasing my chickens. We locked eyes for a moment, and I quickly glanced down at its large, impressive paws. Tawny, speckled fur contrasted starkly with razor-sharp black claws. It ran off to the edge of the woods, first stopping to glance back at me before disappearing into the thicket. I began to think of a series of intaglio prints that would capture the essence of this feral fury.