“Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow room,” I intoned solemnly when things were normal back in the BC days (Before COVID). “In truth the prison, unto which we doom/Ourselves; no prison is.” I winked at my “Forms in Poetry” class to let them know I felt their pain. It turned out to be our last face-to-face meeting for the semester. We were studying the sonnet and I’ve always used William Wordsworth’s love poem to strict forms as a pep talk for beginning prosodists. “And hence for me,/In sundry moods, ‘twas pastime to be bound/Within the Sonnet’s scanty plot of ground.”

Easy for you to say, I tell my three-weeks-ago self. I had no idea what was about to hit us. I’ll bet my shrinking TIAA stash that you didn’t either.

These days, imprisoned, semi-involuntarily, in a perfectly spacious house surrounded by four little gardens, one for each compass point, my husband and I are drawn to intimations of mortality. My 89-year-old very-resilient mother has informed us, via phone of course, that she’s lived a good life and though she’s got plenty of joie de vivre left, she’s prepared. For what, we don’t say out loud. Two of our kids are telecommuting in Brooklyn and are fine; a third is a surgical resident in a NYC hospital and she’s healthy so far but not fine of course–she’s too smart to be fine. She confronts mortality professionally.

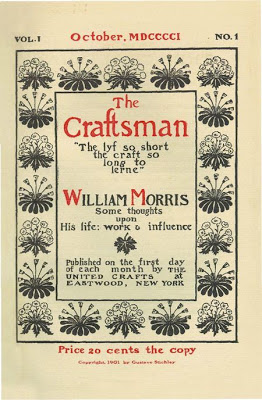

Mortality. I’ll get to Wordsworth’s “Ode” in a bit. But I can’t stop reciting the beginning of Chaucer’s “Parliament of Fowls.” It’s the one I rhapsodized about when I taught Rhyme Royal earlier in the semester. That first stanza ranks as one of the great artistic anthems. It’s not an ars poetica, exactly, but it has lately come to me as a terrible and swift sword. The Halleluiah and Amen and Selah sort. No matter how long, life is short. The job is to make enduring art.

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,

Th’assay so hard, so sharp the conqueringe,

The dredful joye alwey that slit so yerne,

Al this mene I by love, that my felynge

Astonyeth with his wonderful werkynge

So sore y-wis, that whan I on him thinke,

Nat woot I wel wher that I flete or sinke.

How short is the life? How long is the art? My brilliant and talented MFA students didn’t get to go this year to the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference. My university brings our students to this annual 3-day meeting where 15,000 published and aspiring writers, publishers, journals, non-profits, and teachers gather for readings, panel discussions, meet-ups, and a massive tradeshow we call the Bookfair. It breaks my heart that my talented and dynamic students didn’t experience the community and the dizzying possibility that AWP represents. One student has just this week sold at auction his YA novel-in-verse in a two-book deal to Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It’s the most cheering news I’ve had in a long time. And still, his triumph belongs to the threadbare category of Publishing in the Time of the Pandemic.

I have a recently published book of poetry and most of my plans to flog it have evaporated. Who am I to complain about not being able to sign my books at the AWP Bookfair, be part of a cool reading with my students and the folks from the radical anthology Women of Resistance? Not read with Fiona Sampson at London’s hottest new feminist bookshop, Second Shelf? I’m disappointed but I need to say this: No one I know has – yet – lost a job or died. Yet. In the last few days, friends in Italy are mourning loved ones who died after weeks on ventilators. And friends here are worrying about what will come next, and their next paycheck.

Crabby. That’s what I tell people who ask how I am. I take a mental health walk in nearby Van Cortlandt Park. I see a meager strip of daffodils and it plunges me into shame. I realize I’ve been misunderstanding Wordsworth for years. Throughout his body of work, he balances loneliness and human company, balances the effects of nature and human work in educating the person and the soul. Now I realize that terror suffuses even “the blessing in the gentle breeze” which starts his epic “The Prelude or Growth of a Poet’s Mind.” This great poem crosses the metaphoric river of his life by touching down on a series of rocks he calls “Spots of Time.” One of the first is the famous stolen rowboat scene. He’s tacking across a dark lake when, from behind the small peak with which he is navigating, a bigger one appears with “voluntary power” and, grimly looming ever larger, “with purpose of its own//Strode after me.” It’s a scene of boundarylessness. It’s not the peak that overwhelms the boy but the boy’s anxiety that overwhelms the fixed and known natural world. Wordsworth ends this passage with a line I never before paid attention to: “My brain/Worked with a dim and undetermined sense/Of unknown modes of being; o’er my thoughts/There hung a darkness, call it solitude/Or blank desertion.”

If this were a face-to-face class, dear reader, I’d ask you the questions I’m asking myself of late. Are the daffodils in “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” a balm for or a provocation of solitude as “they flash upon that inward eye/Which is the bliss of solitude”? Is voluntary solitude a desertion? And if so, by whom?

I wandered lonely as a cloud today. I wandered lonely and also anxious, waving to neighbors from approximately a six-foot distance while I bowed my head and cold-shouldered strangers walking too close. Everyone had the same idea this Shabbat. But why must the paths be so crowded?

I’m a regular synagogue goer. My clergy and my congregation inspire me daily but the synagogue has been shut since the spring holiday of Purim. After some painful discussion my husband and I cancelled our big annual Passover Seder. Our kids applauded us for being among the “good Boomers.”

Meanwhile, on his off days, a medical-student-volunteer for my mother’s closed senior center is delivering meals to the homebound, which is to say all of them. He arrives cheerful and mask-less and glove-less. My first thought is, I can’t imagine a better vector to spread COVID-19 to the vulnerable. My second thought is jealousy – more a feeling, sure – that my mother has had a face-to-face conversation with someone new.

How am I? Inexplicably lonely and depressed.

I’ve been exchanging wink, wink, nod, nod quips on Facebook with the poet Devon Miller-Duggan, whose historian husband teaches a course called “Plagues and People.” I’ve been exchanging WTF questions with the poet Moira Egan, whose husband is an epidemiologist in Rome. My husband is a professor of Public Health and the author of Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics from the Black Death to Avian Flu. These days he’s busy with TV and radio interviews and is writing a reassuring and analytical COVID-19 blog at the American Scholar. Many people tell us he has calmed them down. Philip Alcabes is putting it together.

I’m coming apart.

So please, dear friends, gather round the cyber fireplace and let us read together “Ode,” which some of us know as “Intimations of Immortality,” others as the “Mortality” or “Great Ode.” Wordsworth started the poem when he was 31. Nearing his 50s he revised and added an epigraph “The child is the father of the Man,” explaining to his friend Catherine Clarkson that “The poem rests entirely upon two recollections of childhood […] and […] an indisposition to bend to the law of death as applying to our own particular case.”

Wordsworth is working out how adults who have seen and lived through difficulty might yet integrate our early childhood sense of the divine, of infinite immortality and comfort with our darker knowledge. Stanza V tells us “Not in entire forgetfulness/And not in utter nakedeness/But trailing clouds of glory do we come/From God who is our home.”

Wordsworth conceives of our growth as a series of play-acting scenes, as we fit our tongue to “dialogues of business, love or strife…down to palsied Age.” By the end of the “Ode” he arrives at something close to what Jews say in our morning prayers. First, we thank God for the miracle of waking up and the miracle of our bodies.

Praised are You, Lord our God King of the universe, who with wisdom fashioned the human body, creating openings, arteries, glands and organs, marvelous in structure, intricate in design. Should but one of them, by being blocked or opened, fail to function, it would be impossible to exist. Praised are you, Lord, healer of all flesh who sustains our bodies in wondrous ways.

Then we say, “You illumine the earth and its creatures with mercy (rachamim); in Your goodness, day after day You renew creation.”

The mercy and the renewal is what Wordsworth yearns for at the end of the “Ode”:

The innocent brightness of a new-born Day

Is lovely yet;

The Clouds that gather round the setting sun

Do take a sober colouring from an eye

That hath kept watch o’er man’s mortality;

Another race hath been, and other palms are won.

Thanks to the human heart by which we live,

Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

I’m crabby in these days of CE (COVID Era). I guess that means I’m afraid. Death is coming for us, but we should have known it always was, one way or another. That’s a knowledge too deep for tears. So I need to find our human heart’s tenderness as well as joys and fears. I inhabit a fraught solitude, avoiding the CDC projections of infection and death rates. I hope to enact Wordsworth’s poetic braiding of two key words from the Psalms, rachamim and chesed, tender mercies and lovingkindness. “Intimations of Immortality” urges us to remember we are born from these divine attributes. “Bliss” is our ability to connect to them. Rachamim comes from the Hebrew word for womb, and it suggests an infinite compassion and patience that comes from a mother or, as the morning prayer articulates, the one who creates and “renews creation” every day. In these days when it seems destruction outpaces creative forces, I pray we can all find a way to reach back to the optimism and infinite possibilities of our youth. Neither Wordsworth or I think it’s that simple. But we both think it’s a start.

Judith Baumel is a poet, critic, and translator. She is Professor of English and Founding Director of the Creative Writing Program at Adelphi University.