S. TREMAINE NELSON interviews DON SHARE

S. Tremaine Nelson first saw Don Share’s name not on the masthead of Poetry, where Share is the Senior Editor, nor in the online annals of The Paris Review Daily, where his poems have recently appeared, but on Twitter, where he once responded to one of Nelson’s favorite Stéphane Mallarmé quotes. After Share’s work was published in Issue No. 01 of The Common, Nelson reached out to him via email to discuss place, space, and the new sphere of internet communication.

*

SN: Where were you born and raised?

DS: Born in Ohio, but raised in Memphis. Frost was born in San Francisco, so if he’s considered to be a New Englander then maybe I can say I’m a Memphian!

SN: Have you lived outside the United States for an extended period of time?

DS: Yes, I lived in Denmark as a child.

SN: Can you talk about the role of “place” in your poems?

DS: Place is everything in my poems. It’s a bit like that Tom Waits song, “Anywhere I Lay My Head.” Wherever I am, that’s what my poems call home.

SN: The Common is based out of Amherst College. Is there a particular style you’d identify as “representative” of New England poetry?

DS: Maybe so: stony, diffident, ambitious, smart…

SN: Have you observed geographical differences in American poetry? Are West Coast poets different than Midwest or East Coast poets? How about urban versus rural poets?

DS: Yes to all of the above. I’ve been following a debate in the Times Literary Supplement about what the French, and winemakers, call “terroir.” It’s the idea that factors like soil, weather conditions, and geology interact with genetics to produce a very particular flavor. It’s controversial in wine making, I gather; but when it comes to poetry, I believe in it.

SN: Your poem “The Crew Change” appears in Issue No. 01 of The Common and, for me, evoked the feeling of American suburbia. Does this poem “take place” somewhere specific?

DS: It does, indeed. That’s all I can say without getting into trouble.

SN: “The Crew Change” reminded me, very strongly, of Ferlinghetti’s work, particularly in its evocation of lust. Would you cite Ferlinghetti as an influence? Or other poets, whose work is explicitly sexual?

DS: You know, like so many other folks, Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind was a great roller coaster of a read when I was young and starting out. But I wouldn’t cite him as an influence. My influences, such as they are, seem to have a kind of sexuality that I wouldn’t be capable of embodying, even if I wanted to. No, in the sexuality department, my axioms have to be proved upon my own pulses, to mangle a phrase from Keats.

SN: “Wishbone,” also appearing in Issue No. 01 of The Common, was a very funny poem to me. I laughed out loud when the narrator says, “But I go on cleaning myself — why shouldn’t I?” Could you talk about humor in your work?

DS: I don’t start out thinking that a particular experience is comedic, but comedy reveals itself unexpectedly, unlike tragedy, which you can spot coming a mile away. I never set out to be funny, but it turns out that I am, sometimes anyway. I did a reading once in The Common‘s hometown, Amherst, of several poems that I thought were grim, wrenching, angry, and poignant. HA! My audience laughed all the way through. I was taken aback till I realized there really WAS something funny going on in my silly excruciations. It’s like when you go to a horror movie and people instinctively laugh at all the gruesome bits.

SN: Your third poem that appears in Issue No. 01, “High Holidays,” mentions “the famous feral parakeets of Chicago,” which made me wonder: is this really a thing? Are there actually feral parakeets in Chicago?

DS: As the comedians say: I don’t make this stuff up! There actually are feral parakeets in Chicago. They’re also to be found in such places as Brooklyn, Austin, and Miami: Myiopsitta monachus (the Monk, aka Quaker Parakeet/Parrot) to be precise. Those birds are escapees, like the rest of us.

SN: You and I have interacted via social media, but never in person. What are some of the pros and cons of social media in the poetry world?

DS: Social media can give a feeling of immediacy to things going on in the poetry world, and that’s a good thing: you can find out about books, essays, reviews, events, awards, and so on, that otherwise might have escaped your notice. I like that it gives a vibrant sense of what’s what. And when I tweet links to pieces we’ve published in Poetry, I get feedback right away, which is good. It makes the editorial process less of a black box.

The downside is that social media can be a vehicle for vitriol, vituperation, and invidiousness, so… it can be depressing, demoralizing, and for some folks overwhelming. It can be misleadingly focused on the here and now, because our tweets and status updates are entirely ephemeral. Also, you can get a false sense of knowing someone. I guess if you’re sane, it’s all fine. There’s no doubt that as an editor, I get an awful lot out of social media — but I think if I were doing something else, I’d be far less involved in it.

SN: Can Twitter force us to better concentrate on language? Or will it destroy our appreciation of the written word?

DS: I don’t think it does much for concentration, no. The brevity of tweets isn’t quite the same thing as concentration. And as poets like Geoffrey Hill have pointed out, the compression in tweets is not the same as compression in poetry; compression isn’t even necessarily a universal virtue in poetry. Anyway, Twitter, as we all know, can be quite a distraction, or even addiction. I sometimes feel that it reduces my attention span, so I have to go offline and read a big long book to regain my humanity. All that said, there’s nothing about [Twitter] that can destroy appreciation of the written word. No worries there!

SN: Lastly, do you have any advice for young poets?

DS: Oh, the usual: read more than you write, keep your eyes off the prizes, tune out the Zeitgeist, and as Brian Wilson says in “Vegetables,” never be lazy.

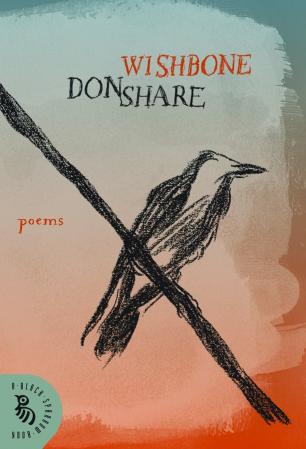

Don Share‘s poems “The Crew Change”, “Wishbone,“ and “High Holidays” appear in Issue No. 01 of The Common.

S. Tremaine Nelson is a graduate of Vanderbilt University and founder of The Literary Man book blog.

Photo of American suburbia from Flickr Creative Commons