The Jungle Cruise

My mother and I are on a chlorinated river that’s somehow simultaneously the Amazon, Congo, and Nile, floating languidly so we don’t run into the boat in front of us and “don’t scare the wildlife”: the kind of joke the Disney guide, in his safari hat and over-pocketed explorer outfit, keeps making.

We round a bend. Animatronic hippos surface plasticky ears amid bubbles. A small, caricatured “primitive” man squats under dense vines—scowling and shaking something. And just as I realize that what he’s holding has lank black hair, the guide calls, “What’s that there in the river, a-head?”

Ba-dum-tss. “A head, ahead!”

In my preteens to early twenties—the decade my family most often drove from Arkansas to Disney World—I never thought the Jungle Cruise was as funny as my mother’s gallows humor or Monty Python, but it was hard not to smile sometimes. As in all Magic Kingdom rides, the script was unvarying, but unlike most, it wasn’t prerecorded. It relied as much on a steady stream (haha) of puns as it did on robotic tigers. Puns turn on voice and timing; the speaker can’t help it: the language begged to fold back on itself. That’s why the joker often says, “Sorry, I couldn’t resist.”

The Jungle Cruise guides didn’t actually even pretend to be sorry. They grinned and started the next one-liner before the groans had subsided. “Tigers are known for their intelligence, but you can’t trust them. You never know when they might be a-lyin’.”

When I was growing up, puns were part of my parents’ repertoire of wordy, nerdy jokes. My mother particularly loved tricky crossword clues that turned on puns, which New York Times Wordplay writer Deb Amlen calls “forehead slappers.”

One of the clearest images I have of my mother’s last bedroom, in an apartment in Missouri where she died of chronic leukemia when I was twenty-seven, is of blue mechanical pencils by her hospice bed. She’d always used those pencils for puzzles—often The New York Times in big paperbacks we’d get her for Christmas—but by then, with her headaches worsening and eyesight failing, she could barely see the boxes. On my last visits, I read clues aloud: “‛Small food’?”

“ORT.”

“ORT? How on earth did you know that?”

“Oh, it’s used all the time in puzzles.”

“Okay: 3 across: ‘Current events’? It’s five boxes. We’ve got a T already in the first one.”

This was 2001, so I was racking my brain for a five-letter soundbite about President Bush or the human genome. Unlike my mother, her mother, and my sisters, I didn’t inherit a love of crossword puzzles. When I stare at the little boxes, I feel like I’m in a bear trap, or maybe my mind is the bear trap: the jaws gaping, waiting, waiting for that one specific perfect grizzly.

“Oh,” my mother said joyfully after a moment’s thought, “TIDES!”

“TIDES?”

It still took me a minute. Current events.

Cow Town

In many of my earliest memories, I’m playing on the floor of my mother’s sewing room in Fort Worth as the machine whirs and country music plays. My mother sews most of our clothes, dolls for me, curtains for our many windows. As a piano teacher, she favors records of Liszt and Rachmaninoff, but she’s as likely to tune into new and classic country as classical. Although my mother was born in upper New York state, and then raised in Arizona after her father’s death in World War II, she’s been in Texas for over two decades by the time I’m born. We live in the same house where she raised my half sisters: near the Stockyards, less than a mile from Billy Bob’s, a world-famous honky-tonk. Country music is literally in the air, along with our mostly Mexican neighbors’ ranchera.

I sing along to Janie Fricke’s “He’s a heartache / Lookin’ for a place to happen / Temporary satisfaction / If you try to hold on he’s gone” when I’m too young to understand what she means (though, if epigenetics is to be believed, with my maternal great-grandmother cheated on and abandoned by the father of her six children, and my paternal great-grandmother impregnated by a guy passing through Texas, maybe I know exactly, cellularly, the man she means).

My mother grins when Lee Greenwood comes on, singing, “I took a band of gold and made a twenty-four-carat mistake / And turned it into / Fool’s gold, and I was a fool ’cause I let you go.”

In the Arkansas Ozarks, where we moved after our Fort Worth house burned when I was ten, we sometimes took out-of-town visitors to the area-famous hoedown theaters: women in swishy satin petticoated dresses playing fiddles and banjos, and patched-overalled hillbillies stumbling on stage for comic relief to crack puns and pretend to be drunk on moonshine.

My parents enjoyed the shows, and the performers were skillful—if you haven’t heard two people fiddle-duel “Orange Blossom Special,” making their fiddles sound like trains, you maybe should—but the shows also stereotyped gender, poverty, and race (if it was mentioned at all in the very white Ozarks). By my teens, I tried to avoid them. As a self-defined alternative teenager in our hippie-artsy town, I was devoted to The Cure and R.E.M. My friends and I drove VW bugs; one had a giant seventies Oldsmobile we called “Boat of Car” after the They Might Be Giants song. We never listened to country.

During my MFA in Florida in my early twenties, when my professor Padgett Powell critiqued the characters in my short story for being “on the correct side of the NPR dial,” I was offended and confused. Why wouldn’t I want them to be?

Although I didn’t overtly think I was distancing myself from having grown up in Arkansas and from the rural Texas poverty of my father’s family, I didn’t write or talk about either. My characters did not wade in cow ponds, as I had as a preteen, or climb over barbed wire into the fields around a rural Arkansas house on a hill called Rocky Top. I didn’t tell—have never told until now—about going to those hoedown shows. Or that, as a preteen, before I knew better, I’d dreamed of growing up to be like those women in taffeta dresses glowing under stage lights with their fiddles.

I never told people that my paternal uncles, cousins, and second cousins still lived on one dusty piece of land outside Fort Worth, where my grandfather had grown up with nine siblings in a one-room house (still standing in my childhood). I left out the junker cars, trailers, dogs in handmade fences. I left out that family’s sense of humor, akin to my own mother’s gallows humor, with even more inexplicable traumas. In one way, my cousins’ cheerfully told stories of miscarriages and drunk-driving wrecks and lost jobs and memory loss seemed like some Baptist form of Buddhist acceptance. This is how the shitstorm of the world is. What are you going to do but ride along in it, hope you don’t get swept into the sewer? But in another way, the stories seemed terrifyingly naïve or resigned.

Like when my cousin Ashley described her brother blacking out beside the semi he’d been hired to drive, and months later just beginning to remember who his wife and son were. “Maybe something in the gas fumes?” Ashley said. “He didn’t recognize his own boy, and you know what? Gail found Dave out in the backyard digging this big ol’ hole, and she said, ‘What are you doin’ that for?’ And Dave said, ‘I’m gonna dig this hole til my daddy’s memory comes back.’ He must’a thought it was like diggin’ to China or something.”

Ashley laughed in that well-isn’t-that-the-darndest way.

It’s not a country song, but it could be: I was trying to dig my way back to you, but now I’m just stuck in this hole.

Being on the correct side of the NPR dial and having read A People’s History of the United States, I knew that it wasn’t my Texas family’s or other rural poor people’s moral failing or lack of hard work that had left them in these circumstances. I knew to blame our wildly unequal capitalist system. But, exactly because of that, I wanted to rage against the machine that hired uneducated workers to drive semis with toxic fumes. I didn’t want stories or music that ended only in knee or forehead slapping.

And when I moved to San Francisco at twenty-six and my mentions of growing up in Texas and Arkansas were frequently met with jokes about inbred cousins and Deliverance banjos, I learned to put even more distance between myself and my country past. The liberal Bay Area was often better at being liberal about what was familiarly leftist. When people asked, “Where’d you move here from?” I started to say, “Florida.” Coasts were acceptable. (And Florida Man jokes hadn’t taken off yet.)

In my thirties, when an artist-hipster friend in Oakland asked if I liked “old-timey music,” I unhesitatingly said, “No.”

Maybe my swirl of real emotions read to her as confusion, because she gushed, “Oh, I think you’d like it if you heard it!” She clearly found fiddles and twangy singing novel: a “past” you could visit, not a place that real people came from.

The Jungle Cruise

My mother was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1998, right before I finished grad school in Florida. But by then, she’d already been sick for several years.

It began the fall she turned fifty-nine when she called me at college to say she’d developed sudden, terrible arthritis. One day her elbows would feel so stiff she’d have to rest while hanging clothes. The next day, she’d walk the eighth of a mile to our mailbox on the county road in Arkansas, and her knees would constrict so badly she wasn’t sure how she could walk back.

Once she told me, “I thought I was going to have to crawl back.” I pictured her like Christina in Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World, dragging herself up the driveway’s chert. It was a terrifying image, but my mother had raised me to believe that any of us might someday find ourselves in a bleak Wyethean landscape. She’d always tended to suffer, not silently, but while refusing help. She hardly ever went to doctors.

But after six months of her worsening pain and exhaustion, my father insisted. And it turned out that my mother wasn’t suddenly aging. She had migrating arthritis from Lyme disease.

Despite my father’s frequent mowing, our hilltop in Arkansas had areas of high grass and jungly vines and dense brush, as the Ozarks do. And at the lawn’s edge was a huge patch of blackberry bushes. My parents used to get up before dawn to pick buckets of warm, dark berries—coming inside, waists ringed with red bites from tiny chiggers, and sometimes small or larger ticks, like new, crawling freckles.

“Do you remember finding a tick embedded in you?” the doctor asked.

My mother would have pulled it out with tweezers if so, crushed it between her fingernails, dropped it in the toilet, taken a shower. This was part of country living. And Lyme disease wasn’t yet common in the Ozarks, so we thought of ticks as inconvenient, not potentially life-altering.

My mother was lucky: she recovered. In another year, she was hanging loads of laundry, refinishing furniture, picking blackberries, and making cobblers.

But then, during my first year of grad school, she came down with a flu that wouldn’t leave. She’d be in the middle of cooking dinner and have to go nap (she’d never napped). This time, the doctor diagnosed her with mono, though admitted that, past sixty, she was the oldest case on record.

“I’ve always wanted to be exceptional,” she joked.

Then a perfect storm happened. I mean a bad confluence. But also, there was fake jungle thunder.

It was my second year in the University of Florida’s MFA. My mother was well enough that my parents came to visit for spring break, and as we often did, we went to the Magic Kingdom. In the afternoon, we were in line for the Jungle Cruise, slowly snaking through an area with extraneous coils of hemp rope and big wooden boxes marked CARGO.

Despite the awning and fans, the Jungle Cruise line always seemed hotter than other lines. Maybe it was the power of suggestion that we were headed from Florida’s tropics to the real tropics. We were on our way to see “crocodiles” and what I was fully coming to understand were racist caricatures of “jungle people” with their whooping and drumming and shrunken heads. Heart of Darkness, with “The horror! The horror!” replaced by “A head, ahead.”

My parents, my husband, and I were talking and joking around and standing stickily in that line, listening to the crackling of fake thunder and rain, when my mother, as she later described it, “felt something fall inside.”

She didn’t tell us. She just climbed into the boat when we finally reached it and grinned along with the guide’s jokes, and got sprayed by the robotic elephants, and maybe subtly touched her abdomen. After, she ducked into a bathroom by Tom Sawyer’s landing to see if she could see anything. She couldn’t, but she could feel “a bulge.” Still, she didn’t say anything. She spent the rest of the afternoon walking in the oppressive Florida steam, taking pictures of topiaries and eating Mouseketeer Bars. Finally, that night, back at the hotel, she said, “I didn’t want to alarm you while we were at the park, but something has fallen in my body.”

Of course we were alarmed. This sounded serious. “What did it feel like?” we asked.

“Just heaviness, sort of a pulling, but no real pain. I’ll just check with the doctor”—a seventeen-hour drive away—“when we get back to Arkansas.”

Maybe, after years of Lyme disease and mono, this new “bulge” really didn’t seem serious. Or she didn’t want to face a new sickness. Or she thought, as she always used to say, she should just “buck up.”

This was still the days of early internet and before cell phones, so we couldn’t search symptoms. We didn’t imagine her uterus hanging into her vagina. We didn’t know a uterus could prolapse until days later when the doctor back at Carroll County Hospital in Arkansas told her.

This happens sometimes with age, he said. It’d be a simple surgery. They’d run the pre-op bloodwork.

But when the bloodwork came back, it showed something strange. Her white cell count was so high her body appeared to be fighting a raging infection. Something worse than mono.

This didn’t make sense, the doctor said. They’d have to put the surgery off until her body was more stable. They’d run blood tests again in a few days.

But those tests looked no better. So the doctor ran more and different tests. And within a week, my mother was having surgery for a prolapsed uterus with the understanding that it was the least of her worries. She had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (which, in retrospect, she’d probably had for several years underlying, or confused with, the Lyme disease and mono). She would never actually be well again.

The Cow Parade

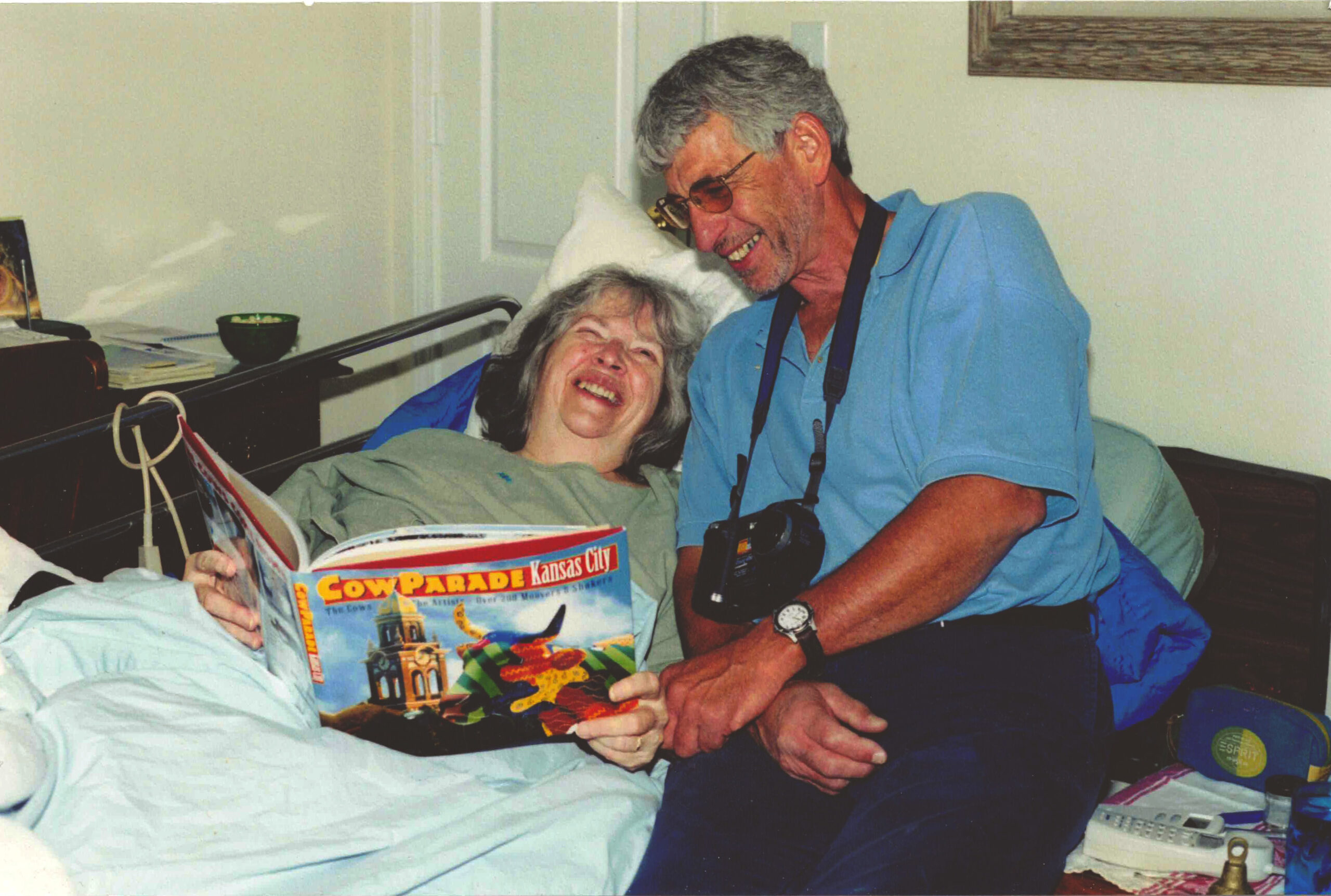

After I moved to San Francisco in May of 2001—which turned out to be only a few months before my mother would die—she started sending me pictures of cow statues. The Cow Parade had come to Kansas City, where my parents were living by then.

Like Fort Worth, Kansas City is a former cow town—with once-thriving stockyards for cattle drives west—though the Cow Parade didn’t originate there. The phenomenon started in Switzerland and spread to U.S. cities in the late nineties and early 2000s. The premise is that hundreds of artists receive and then transform the same blank white fiberglass statue (or variations; there were three cow bodies: reared up on back hooves, grazing, and lying down). The artistic gimmick and title almost always revolve around a pun.

There was Cowlvador Dalí, with a clock slumping over its back as it grazed. Charlie Parcow reared on hind feet on a stack of giant records, his midnight-blue body in an evening jacket, his front hooves poised on the sax’s keys. The Cowardly Lion (which my Oz-loving father posed by), with its mane like shag carpet dipped in plaster. Moo-lyn Monroe, balancing in heels on her hind hooves, dress swirling up provocowtively.

My mother had just survived a near-death fever the fall before. She was often weak from the leukemia, and nauseated and headachy with what would soon be diagnosed as a brain tumor. Yet, on the days she could, she was determined to see these cows.

I imagined her holding the insert from The Kansas City Star with its map of businesses and streets, circling in mechanical pencil, if her vision was good enough, or having my father circle, the most unmissable cows, the way she used to spend hours poring over maps before our weeks-long road trips all over the country and to Canada. I felt embarrassed for her.

And, also, I felt sick with guilt. The summer before, I’d moved from Florida to Kansas City to live near her, maybe, I’d said, for as long as she lived, but then I’d left for California after only six months. At that point, she really did seem like she might live several more years, and as a twenty-seven-year-old still fighting to define myself as not my parents, I desperately wanted out of Missouri, where I’d gone to undergrad near Branson’s country shows, and which I’d already escaped once.

My mother wasn’t sending me the pictures to guilt me about leaving but because she thought they were fun, and that made me feel even guiltier and sadder. I wanted her to use the end of her life for something artier, smarter. But what kind of daughter was I for judging my dying mother? But also, what kind of educated, art-museum-loving mother would like these cows?

I stared at the glossy picture of Cow-moo-flage: a grazing cow hidden in plain view beneath a giant yellow beak and comb, like Foghorn Leghorn with angelic wings. It could have been the ur-title for the whole parade: so obviously a cow pretending to not be a cow—like a kid in a Darth Vader mask who keeps taking the mask off to announce, “Look—I’m not me; I’m Darth Vader.”

Although I didn’t want to hurt my mother by insulting the Cow Parade—and I’m sure I told her on the phone how great the photos were—I was actually relieved to be in San Francisco (where, I didn’t realize, the Heart Parade would come soon—you know, I left my heart in…). I couldn’t imagine posing by the cow statues, pretending I thought they were clever. Sure, you could stick the word cow into a lot of other words, but why would you want to?

In one of the pictures, my mother was wearing, as she often did, a handmade smocked sundress and Birkenstocks. Her hair, which had had gray streaks just in the bangs for a decade, was completely white. She was still heavy, as she’d been most of her life, so she looked in one way solidly embodied, but there was also something frail about her. Exhausted. As if she might not be able to stand back up. She was on a red velvet seat, which had been hollowed into the side of a white-and-black-spotted lying-down cow.

On the back of the photo, she’d written: Cowch.

The Jungle Cruise

My mother did not ever want to be “trapped in an infirm body.” This was what she used to say, had been saying for almost two decades, long before she had any infirmity.

The first time I remember her saying it, we were leaving the high-rise nursing home in Buffalo, New York, where her maternal grandmother was living. I barely remember Grandma Siggins, but there’s a picture of her and my mother on the lawn. Grandma, in her nineties, looking faded and wrinkled as the cloth of her flowered housedress, is in a wheelchair.

“It’s so terrible,” my mother said as we pulled away. “Her mind is just as sharp as ever, but she’s trapped in an infirm body.” More than losing her mind—as her own mother would to Alzheimer’s—my mother feared this. She prized being capable, mobile. If peaches were ripe in Southern Arkansas, we’d drive half the day to the orchard to buy boxes of their sun-warmed velvet that my mother would boil into peach butter or bake into cobblers with homemade biscuit toppings. If the antique store had a scratched oak table, my mother would strip and refinish it. If our land had blackberry brambles, she would rise before dawn to pick tubs full before the day’s heat descended.

If there was a meteor shower, she’d wake me at midnight so we could lie on our backs in the yard on handmade quilts. If my father had two weeks off, she’d spend days planning road trips, loading the car, shuttling us out in the dark so we could cover the first three hours before the sun even rose, because we had to make tracks: we were driving from Texas all the way to Montana to see Glacier National Park. (Though we did have to stop sometimes to photograph clouds, which she loved to take pictures of—their cirrus wisps and cumulous castling.)

Who would she be if she couldn’t do all this? If she weren’t ready for anything?

She loved, as I did, those J. Peterman catalogs of the 1990s, with their hand-drawn pictures of clothes accompanied by stories. The best item—but pricey, so neither of us ever bought one—was their simple black travel dress. As the narratives explained, it could be converted, with just the addition of a scarf and heels, into evening wear. With a belt and sturdy sandals, into an outfit for climbing pyramids. With layers, it became the perfect afternoon dress for eating yak cheese in a Siberian yurt. With a wide-brimmed safari sunhat, a dress for pushing through jungle overgrowth.

The dress, and any woman in it, was like a Swiss Army knife. Exactly the kind of capable-for-every-new-circumstance woman who my mother most wanted to be. So, when she was diagnosed with chronic leukemia, it wasn’t a surprise or extended family discussion that she refused to consider chemotherapy. She didn’t want to live any longer than her body was naturally ready to. Rather than face the effects of treatment, she would go toward the unknown. If she had to, she’d convert her handmade dress into a gown for a hospice bed, or into a shroud for her own death.

Cow Town

In 1952, two decades before I was born, my mother moved to a house near the Fort Worth Stockyards as a newly married seventeen-year-old. One of her neighbors and first close friends was named Brenda. In my mother’s favorite story about young Brenda, she and her fiancé, Ken, were so broke that on Valentine’s Day, in place of a gift, Brenda bought a cheap roll of satiny ribbon and wrapped it around her naked body. When Ken got home, she walked down their apartment stairs—red-haired (as she was) and wound only in that red ribbon.

This clearly impressed my mother, who had always been shy about her body and valued scrappily seeing and creating beauty where it wasn’t obvious.

By the time I knew Brenda, Ken was a doctor, and they lived in a fancy ranch-style house in Arlington. Though Brenda was only in her forties, she had long since given up nakedly flouncing down staircases. She’d been diagnosed with scleroderma a few years after she and my mother met.

For the decades since, day by day, her skin had been gradually suffocating her. As it lost its elasticity, it pulled tight against her jaw; it concaved her cheeks; it closed her fingers into claws, then fists. It constricted her throat, which looked, like all of her, almost transparent. She was in a wheelchair and could not move her hands to pin up her own red hair, which, piled high, still gave her a sort of china doll beauty. Eventually, her skin would shrink-wrap her lungs and stop her from breathing.

I’m not saying that physical mobility equals quality of life or that my mother ever overtly said she feared becoming like Brenda. But when I think of my mother’s decisions about her own death, I see Brenda, dressed up by her helper for our visit—unable to stand on her own. Unable to hold a pen to write (she was a poet) unless a helper stuck it between her fingers.

The Jungle Cruise

When my mother was first diagnosed, she kept reassuring us that chronic leukemia meant she could live for years. She would be well for a while, then less well, then less. But that is not at all what chronic means. Or that’s not what happened.

For the three years after her diagnosis, she’d have months when she’d feel energetic enough to go for walks or cook elaborate new recipes, as she’d always loved to. She’d do crossword puzzles. She’d travel. But then she’d catch a flu, and her fever would spike so high she’d be in bed, nearly delirious, for weeks. She’d say, “I think this is it. I think I’m really dying this time.”

Once, when I was still living in Kansas City, my husband and I rented a car and raced to see her. I sat by her bed, and it’s hard to explain how sick she was, except to say that she seemed to be dissolving into water molecules, like a blurry photograph of herself. I cried and cried and looked at the wall above her bed, crowded with family photos all taken by her: glamor black-and-whites of my older sisters and me and a chronicle of Thanksgivings: 1970s headscarves (my sisters) and Little House on the Prairie bonnets (guess who), to all of us in 1980s baggy khakis and too-bright T-shirts, to my quasi-goth lace leggings as a teen in the nineties.

Because she was self-conscious and tended to hide behind the camera, there was not a single picture of my mother, and yet she was everywhere. She had given birth to all of us, to who we were as a family. She could not be leaving, and I was sure this time she really was.

But then the fever broke. We went out to eat (though she had almost no appetite). We saw Memento twice in the theater, because she loved it. We talked in detail about its reverse chronology.

But, a few months later, she was I’m-going-to-die-this-time-but-don’t-worry sick. And we were back in the same long, winding line we’d never left.

Like amusement park lines do, it kept doubling back on itself, so we’d find ourselves right next to where we were months before, and sometimes we’d get so close to climbing on the boat that I could see the river lapping at my sandals, all the world’s crocodiles and alligators beneath that water. Here it was, the ride I couldn’t even say the name of: My Mother’s Death.

But then the guides would load the boat from some other line. My mother would recover from the fever. She’d get some of her strength back. For days or weeks, we’d loop back away again.

But then she’d feel new pressure in her abdomen. The doctor would explain that her spleen was now “way big.” He really said that, like a surfer talking about a giant wave. It sounded funny, but what he meant was horrifying: white cells had filled her spleen. Her organs were starting to fail. She was trapped in an infirm body.

On every side were huge cargo boxes marked GRIEF, and I was exhausted with grieving and waiting for more grieving. Sometimes, I wanted out of the line, whatever it took. Even if it meant her dying, because to wind back and forth like this, closer and farther, felt unbearable.

It’s no wonder I fled Kansas City. Staying felt like announcing that I was waiting for her to die, and of course all I wanted was not to think of her dying (though of course moving didn’t help).

On the day I left Kansas City, my parents came to my apartment, and my father took a picture. In it, my husband and mother and I are standing in the dim lobby. I’m holding a pan of homemade brownies my mother has been well enough to bake, or has forced herself with her limited energy to bake because she loves us. The camera flash shatters against the aluminum foil, but despite the flash, my mother isn’t blinking. Her eyes have a hopeless steadiness behind her bifocals. I can’t place the expression, but the longer I look at it, the more I feel sick with the knowledge that my mother thinks at that moment she is seeing me for the last time.

She knows, though I don’t yet, that the ride I am waiting for is not just her death, but all the years that she won’t see me living. She will never see the real love of my life, whom I won’t meet for five years, after Will and I divorce. She won’t see me wondering if I look like her: holding up the picture of her at sixteen beside my own face in the mirror, her brown hair waving toward her shoulders, bow lips, slightly round face, casual but somehow 1950s movie-star glamorous in a gingham shirt.

She won’t see my first book get published. She won’t see me crying on the floor of apartments for years after she dies—suddenly struck down in the midst of whatever I’m doing by the migrating arthritis of grief.

But even that time she thinks she’s seeing me for the last time isn’t the real end. She visits San Francisco a month after Will and I move there. We go to Cliff House and reenact pictures of scenes from Harold and Maude. We go in the Camera Obscura; we eat Italian food back in the Lower Haight. But, in the midst of lunch, my mother is struck with a blinding headache. On the Amtrak to Kansas City, she’s so dizzy my father has to help her walk down the aisles. When they get home, she falls suddenly forward onto a cedar chest and splits her forehead. My father rushes her to the E.R. It turns out she’s developed a brain tumor.

I fly back for Labor Day. Again in October for our birthdays. By then, she can barely get out of bed. She apologizes that she won’t be able to make me the birthday tiramisu she’d planned. She can’t sit up for more than a few minutes, even with the hospice bed helping. She’s in a new kind of pain she describes as lightning the whole length of her spine.

I call the hospice nurse, who says, “Give her as much morphine as she wants.”

And my mother jokes, as she’s been joking, “But what if I get addicted?”

Her classic gallows humor. But the gallows are real now. She must know this, because for the first time, she doesn’t refuse the morphine. She lets me open the little bottle, fill the dropper, drop one drop and then another and another into her mouth.

(Moose) Town

If people had made “bucket lists” in the eighties, my mother would have included See a moose. Despite being born in northern New York state, she’d left as a child before she ever got to see one. So, on a road trip through Eastern Canada, when I was maybe seven, she was overjoyed to see a billboard advertising a moose farm.

She and my father agreed spontaneously to go right then. We’d be racing to make it before sunset, but what was an eighty-kilometer detour after driving from Texas to Canada? Finally, she’d see moose: mythical, towering antlers, like cows crossed with trees.

Just before sunset, we pulled through the gates and my father hurried to the farmhouse to ask what we owed and where the moose were pastured.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” the woman at the door told him, “but it died yesterday.”

I’m not sure if my father said, “What?” or just looked dumbstruck, but the woman rushed to clarify: “It’d been sick a while.”

“You only had one moose?” my father said. “And it died yesterday?”

As soon as we got over sitting in the car feeling stunned and sad and mooseless, this became a family joke. The lengths we had gone to for a dead moose. Its tragicomic timing. When something disappointed us, we used to say, “Oh, it died yesterday.”

If my mother could have talked to me the day after her death, I can imagine her joking, “Oh, she died yesterday.” Though, in cosmic-joke fashion, it was hard to tell when “yesterday” was. She died in the middle of the night on October 27, the night Daylight Saving Time ended. We had to live an extra hour of our most immediate grief.

She was the one who’d taught me the mnemonic that clocks “fall back” in the fall and “spring forward” in spring, but that year, I didn’t need to be reminded that time would always be falling backward toward her alive, and it would never fall back far enough. I could never again reach the moment before my father knocked on the bedroom door, his voice like a record almost scratched beyond playing, and said, “She’s gone.” And I ran to the guest room, and she was right there in the same bed—not gone, but gone. Her infirm body there, but her mind no longer trapped in it. Her blue mechanical pencils on the windowsill, waiting for a crossword puzzle, like always.

The Jungle Cruise

I’ve always been afraid of naïveté. I cover my eyes in movies when characters do things that the audience knows will hurt them. I want to rush into the screen and warn them. I want a dress for the safari-river-crossing-mountain-climbing so I’m not humiliated by being unprepared. I want to rush back in time and stop myself with that dropper of morphine.

At the crematorium, when I’ve momentarily pulled myself together from sobbing, what makes me hysterical again is when the man doing the paperwork asks my mother’s date of birth.

“October 13, 1935,” I say. And I suddenly, clearly picture a portrait of her as a baby: chubby, ringleted. She’s sitting like she’s been set down in her white ruffled portrait dress and isn’t sure how to move, her doll-like lace-up shoes jutting toward the camera. She’s smiling at an out-of-frame parent, and her eyes are big and dark brown, or what I know is dark brown, though the photo is, of course, black and white.

It wasn’t possible. That baby, with her little shoes and old-fashioned ruffled socks, could not be the exact same body whose fingernails (look—they’re so tiny, so pale in 1936) were already blue-purple by the time, an hour, and the same hour later, men came from the funeral home to carry her down the apartment stairs. They could not be the same body. Life could not deceive me that terribly.

But of course, again and again, it can, it does.

Cow Town

In 2011, exactly a decade after my mother died, I was hired as an assistant professor in Moscow, Idaho. Huge grain silos, rectangular and cylindrical, loom in the gravel lot at one end of Main Street. Now I think they’re iconic and charming. When I got here, I sometimes thought that, and I was sometimes scared I was in the middle of nowhere. I was scared that the love of my life I’d met four years earlier was going to leave me and move back to Oakland. He’d begrudgingly come, and we were not doing well. He did not want to replace the Bay Area punk shows he’d played with watching a band sing, “You say ‘one ounce,’ I say ‘jig.’ One ounce. Jig. One ounce. Jig.”

He did not love—I didn’t know if I loved either—the surrounding wheat and canola and lentil and chickpea fields (none of which I could have identified). It was an hour-and-a-half drive to the nearest bigger city, Spokane. At points, no radio stations came in. At other points, all you could get was Christian talk radio or country. There were multiple country stations: Bull Country, Big Country, Coyote Country. Some played newer country; some played classic; some played a mix.

I didn’t really know the difference. Once, on our move, I tuned in to keep myself awake. And later, sometimes, when we were driving to Seattle or Spokane, I’d tune in as a joke. All those cold river waters and cold beers and tank top straps and girl-you-look-good-in-those-jeans. Sometimes the songs were a little funny; mostly they were dumb.

But one day, driving to yoga in the midst of a winter depression, I heard a song that I loved despite myself. It started, “She’s so complicated / That’s the way God made her / Sunshine mixed with / A little hurricane.” Then Brad Paisley sang, “And she destroys me in that T-shirt / And I love her so much it hurts.” I wasn’t into this yet. I was now a correct side of the NPR dial assistant professor of poetry, and these rhymes were strained and corny. But then something else happened. Wait for it.

“I never meant to fall like this,” Paisley sings. And then he gets where this has all been heading: “But she don’t just rain, she pours / That girl right there’s the perfect storm.”

The pun made me smile, like after riding one of the janky county-fair rides (which I also rediscovered in Idaho) that’s trying so hard it has flashing lights that say FUN! (with a bulb or five burned out), but you find yourself stepping off dizzily joyous. While I’d been distracted by the cheesy “God” and “T-shirt” lines, a reversal, some sort of linguistic alchemy, had happened. Somehow, via that pun, “perfect storm” ended up meaning both its usual cliched self—a bad confluence—and its inverse: the perfect girl.

I’m not denying the objectification and slight misogyny of that stormy girl. And I’m not saying I’m more likely to listen to Brad Paisley or Blake Shelton than Patti Smith, Rage Against the Machine, or The National. True to form, I’m about to quote an NPR story. In “Puns in Country Music Songs Done Right,” Geoff Nunberg says that a lot of people, like I used to, think country music is “a linguistic trailer park.” He doesn’t agree. He explains that puns are “a fitting device … particularly when they’re tackling [country’s] favorite themes—the fragility of happiness, the loss that’s always immanent in love and family….”

In “Neon Light,” when Blake Shelton sings, “Cried and dried these tears / I don’t know how much more missin’ you I can take. / I prayed, prayed, prayed / For a sign, sign, sign. / Now there it is in the window / … / There’s a neon light at the end of the tunnel,” doesn’t he take the worn-out cliché of the “light at the end of the tunnel” and turn it into an actual bar where people can slap their knees, slap their foreheads, slap each other’s shoulders in sloppy commiseration? Isn’t this Word turned into the sad but also sustaining complexity of real World?

I’d extend Nunberg’s metaphor and say that if a “linguistic trailer park” is a space where language is up on concrete blocks, unmoving, then puns do the opposite. They’re where language moves double-time and transforms.

I didn’t think this all through when I first heard “Perfect Storm.” I just knew I looked forward to listening to it. Maybe I’d regressed to the little girl who’d loved Janie Fricke (with her perfect country name) in her purple ruffled shirt and concho belt. Or maybe I’d grown into someone older and sadder and wiser, like my mother, smiling at her sewing machine in Fort Worth, as Lee Greenwood alchemized all his mistakes into “fool’s gold.”

The Jungle Cruise

From a linguistic standpoint, puns rely on naïveté. You’re deceived into accepting, in seemingly good faith, one meaning of a word or line of logic, only to have it double back on itself, or reverse. Like you accept you’re being born into this body to live a beautiful life, and then realize, and to die a painful death. As Nunberg says, our “innocent reading” of a phrase is made “more sad and knowing.”

Or, as Josh Osborne says, “Lines that twist around themselves or are almost a pun, those are the cornerstones … of country music.” And so often, the lines of our lives are twistier than we thought—or maybe than we wanted to think.

But it’s not that the first meaning is wrong. It’s just part of the story.

The Cow Parade

When I first saw those pictures of my mother with the cows, I’d wanted to stop her from leaving them as part of her last record on earth. Had she become that naïve, that old, that desperate?

No, and yes, I think now. What if she loved the Cow Parade not despite but precisely because the cookie-cutter cows remained so obviously themselves while insisting on being something else?

By the time of the Cow Parade, my mother knew she’d really never again be well enough to spend the day at Silver Dollar City (the old-timey amusement park near Table Rock Lake, where the River Rats played Dixieland jazz she loved) or go to Kansas City brass shows on the Plaza. Lifetime inveterate reader that she was, she couldn’t read more than a few pages. She would never watch another movie with Marilyn Monroe, or spend a leisurely afternoon, as we so often did in my childhood, in an art museum. She would never go back to the Fort Worth Stockyards, where she’d spent more than thirty years, or stand on the Arizona cattle pens in her jeans and cowboy boots as a teenager, or help her older brother rope a steer.

She knew, before I did, that this was all truly ending.

But here were Cowculus, Cowntertop, Jazz Moosik, Moo-lyn Monroe. Even at its most reduced, couldn’t the world still surprise her? Linguist Xiaoli Gan says that puns are multiple meanings “give[n] birth … at once,” and wasn’t it wonderful that so many meanings could be packed into, or born out of, so little space? And wasn’t it wonderful that when she was too tired to stand, she could sit, cowlapse even, smiling slightly, on Cowch?

The Jungle Cruise

When I was a child, in the early 1980s, when everyone suddenly did aerobics, my mother went through a period of putting on a black leotard and tights and bouncing between the grand and upright pianos singing along to “Wasn’t That a Party”: “Could have been the whiskey / Might have been the gin / Could have been the three or four six-packs / I don’t know / But look at the shape I’m in.”

She only drank the occasional Mexican-restaurant margarita, and I seriously doubt she had ever been hungover, so she wasn’t kicking her legs in commiseration. Instead, still quite overweight and embarrassed by her body, she was amusing herself by making herself into a visual pun.

“Just look at the shape I’m in!” Bounce bounce.

It took me decades, until years after she died, to get this joke or learn that the Rovers really sing, “Look at the mess I’m in.” I told you: I’m dense about puns.

I suspect now that my mother felt the same way I do, and probably a lot of people do, about naïveté. To preempt it, she doubled language back before the world could double back on her.

Maybe there aren’t enough words to get at the twisty messy neony lightning-struck painful sloppy beautiful fake real jungle river of being human. We have to use the same words over. We have to lay them right on top of each other. We have to look backward and forward at once. We have to admit that we’re both in and not-in on life’s joke.

Or, as George Strait sings, I’m “Lookin’ out my window / Through the pain.”

Alexandra Teague is the author of Or What We’ll Call Desire, two prior poetry collections, and the novel The Principles Behind Flotation. She is also co-editor of Bullets into Bells. Her poetry and essays have recently appeared in The Massachusetts Review, Boulevard, River Teeth, and elsewhere.