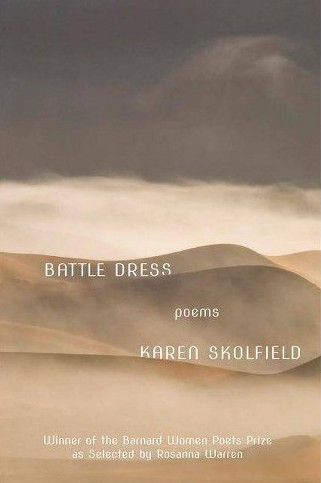

Excerpted from Battle Dress: Poems by Karen Skolfield

The author of this excerpt, Karen Skolfield, will be a speaker at Amherst College’s LitFest 2020.

Enlist: Origin < German, to court, to woo

Perhaps with a desk between,

some chaste space, the recruiter leaning

forward, warm bodies on the other side.

Of the teenagers present

one will lie about her age,

one will eat bananas to make weight,

one pull herself from small-town quicksand.

Lace the hands behind the head,

look good in a uniform, look nonchalant.

Oliver de la Paz is the author of five collections of poetry, including his latest book, The Boy in the Labyrinth (University of Akron Press, 2019). His work has been published or is forthcoming in Poetry, American Poetry Review, Tin House, The Common, The Southern Review, and Poetry Northwest. He is a founding member of Kundiman and now serves as co-chair of Kundiman’s advisory board. He teaches at the College of the Holy Cross and in the Low-Residency MFA Program at Pacific Lutheran University.

Oliver de la Paz is the author of five collections of poetry, including his latest book, The Boy in the Labyrinth (University of Akron Press, 2019). His work has been published or is forthcoming in Poetry, American Poetry Review, Tin House, The Common, The Southern Review, and Poetry Northwest. He is a founding member of Kundiman and now serves as co-chair of Kundiman’s advisory board. He teaches at the College of the Holy Cross and in the Low-Residency MFA Program at Pacific Lutheran University.