By CLARE BEAMS

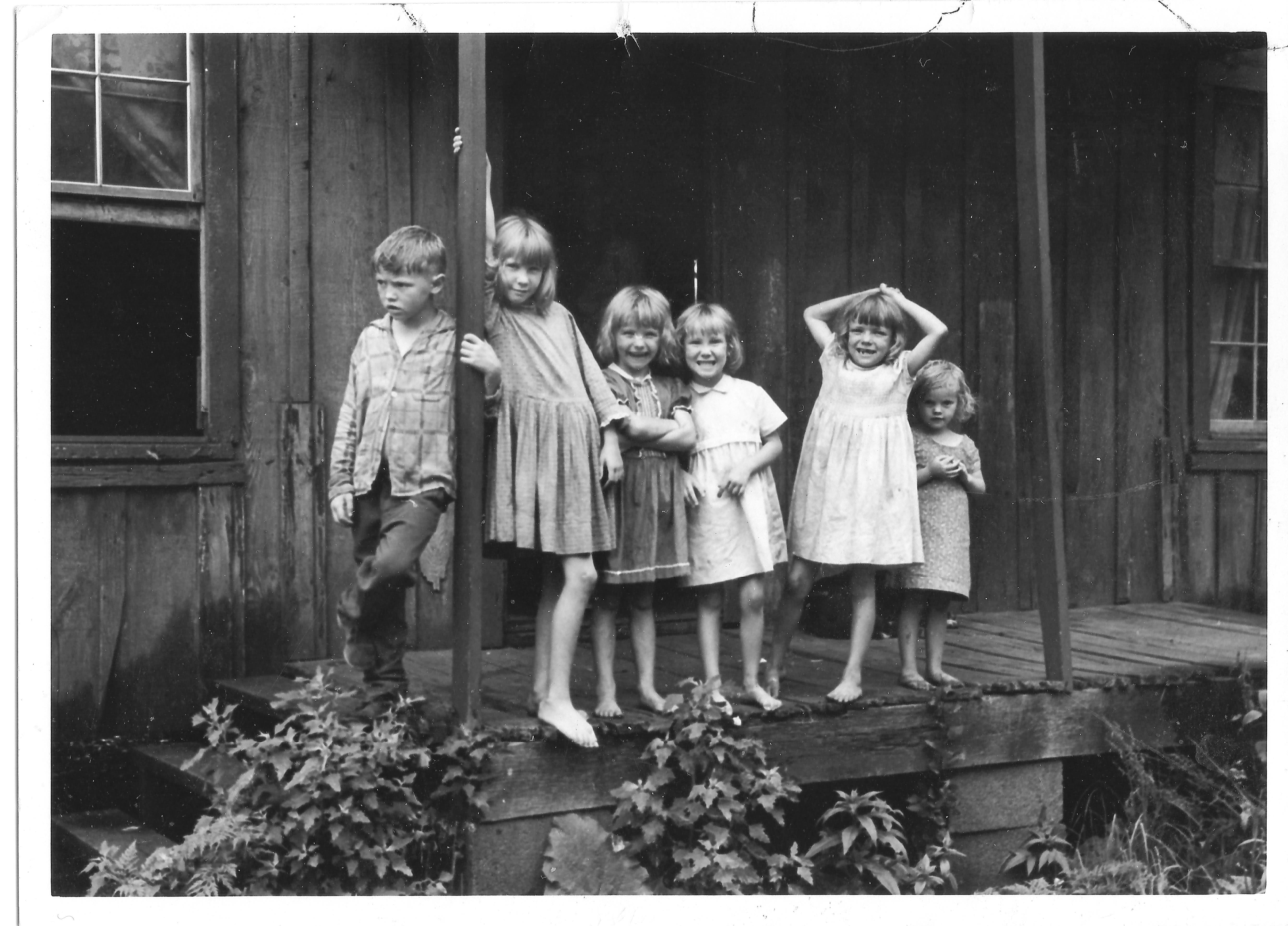

The church ladies were having coffee in the living room of the Baker house when Martin Williams delivered his parachute to Lily Baker, his bride. Only some of the church ladies could really have been there, but in retellings they all claimed seats. They allowed one another this. A natural desire, to be part of the story.