By PHILLIP LOPATE

When, in June 2009, the High Line Park opened to the public, it was declared an almost unqualified success. Some architecture critics nit-picked the design, but basically they endorsed it, and ordinary folk (I include myself in that category), less fastidious, greeted it with enthusiasm. Crowds lined up for hours to have the elevated promenade experience, it became a (free) hot-ticket item in New York City, which typically over-embraces a novelty for six months, then ignores it. Especially in hot weather, the challenge soon became to grab one of the reclining benches on the sundeck and tan yourself for hours, while envious masses stumbled by. The crowded, restless carnival-grounds movement of the park-goers above-ground rhymed the pedestrian conveyer-belt effect of the gridded streets below: Manhattan is a place where loitering in one place is done at your peril. Paris has boulevard cafes for cooling one’s heels, Rome comes to a rest at fountains and piazzas, but in Manhattan you keep moving forward. Well and good: I approve.

Issue 02

Gypsy

By J. MALCOLM GARCIA

1.

I imagine it this way. Gypsy awakens from a restless sleep, stretches. Hears his muscles and bones crack, sees how his curtains absorb the light of a late San Francisco afternoon, and at that moment decides to start drinking again.

He doesn’t remember having a booze dream, just woke up and decided: Today is the day I’m going to get fucked up. Something clicks into place. Thank God, it’s been decided.

For days he had found it hard to sit still, hard to sleep. His body ached from the weight of his bitterness. He tried to read some of his old text books on alcoholism and its treatment, tried to take pleasure in his term papers and the comments scrawled in red, Nice insight! and Excellent observation! but those evening extension classes at Berkeley had been nothing but a betrayal, an illusion of accomplishment, and he tossed the books and his notepads across the room with a rage that kept him awake at night. He had done everything he should, and still he was denied what he deserved.

Realism in Nature’s Garden

By SARAH LURIA and DANIEL JACKSON

Houghton Garden (Fig. 1) was created in 1906, on the grounds of an estate in Newton, Massachusetts, owned by Martha Gilbert Houghton and her husband. Houghton hired Warren Manning, a leading landscape architect and former member of Frederick Law Olmsted’s studio, to work with her on a design for her garden. Manning disliked the kind of formal garden fashionable at the time, which subdued nature with symmetrical, geometric forms. He advocated what he called a “nature garden,” whose design was less invasive, and took advantage of the elements nature already provided. This demanded, as he put it in an essay quoted by Robin Karson in Nature and Ideology (1997):

The Common Statement

This summer, for the first time in my life of weather, I walked through a rainstorm: entered, endured, exited. All within one hundred yards of a smooth country road.

Other firsts: bearing out tornado warnings in the basement of Frost Library (twice); a moment of queasy lilting I assumed was in my head but turned out to be a Virginia-originated earthquake; battening hatches (drawing water, securing heavy items in the backyard) against a hurricane. To be truthful, I have experienced earthquakes and hurricanes before, but the former was in Guatemala, where such things are expected; the latter was in the foreign country of childhood in which parents are responsible for taping the windows, and I was allowed to dance in the driveway in my bathing suit in the warm wet eye of the storm.

A Home for All

By MICHAEL KELLY

Orson Squire Fowler was a man convinced of the links between physical shapes and structures and all aspects of human health. His primary interest was the shape of the human skull and its relation to human intellect and emotions. Along with his brother Lorenzo, Orson traveled throughout the United States in the 1830s and 40s and beyond preaching the new science of phrenology and publishing dozens of books, pamphlets, and magazines on the topic. Along with their partner (and brother-in-law) Samuel Wells, the firm of Fowlers & Wells was the leading publisher in the fields of phrenology, water cure, mesmerism, psychology, phonography, and other health and hygiene movements of the nineteenth century. The most famous product of their press is the second edition of Leaves of Grass (1856), but that’s another story. Through the tireless efforts of Fowlers and Wells, phrenology became part of the American cultural landscape. Edgar Alan Poe, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William James are just a few writers who either had their heads examined or commented on phrenology in their work.

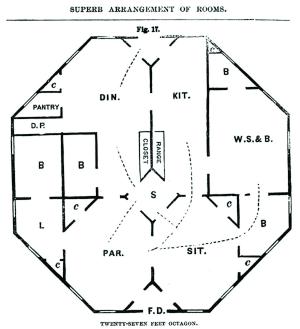

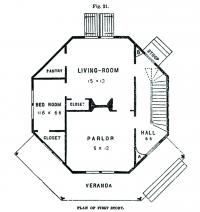

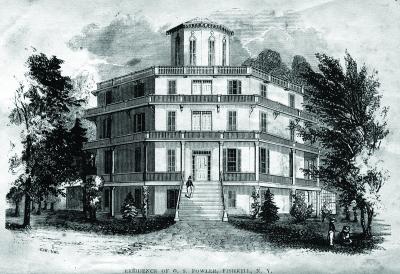

To a mind as creative as Orson Squire Fowler’s, the leap from phrenology to architecture was a logical one, especially when he began building a home of his own. His quest for self-improvement and self-sufficiency led him to explore new directions in home design and construction. In 1848 he published the first edition of A Home for All, which opens with a simple declaration: “To cheapen and improve human homes, and especially to bring comfortable dwellings within the reach of the poorer classes, is the object of this volume—an object of the highest practical utility to man.” In spite of his concern for the poor, throughout the book Fowler argues for improvements regardless of cost because “improving home facilitates, aids every other end and pleasure of life, while scanting it scants all.” The whole of Fowler’s book is a curious blend of pragmatism, self-sufficiency, and excess. Why build a one-story home when four stories are better? Why limit yourself to a handful of rooms, when more rooms will provide more space for exercise and play and guests? “My own house has sixty rooms, but not one too many.”

Orson Squire Fowler. A Home for All or, The Gravel All and Octagon Mode of Building. New York: Folwers and Wells, 1854

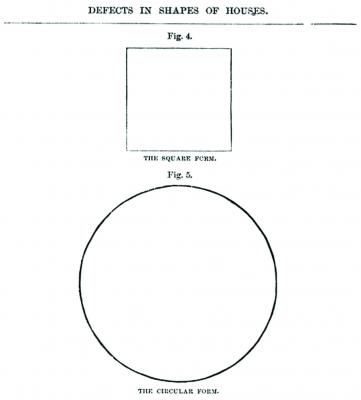

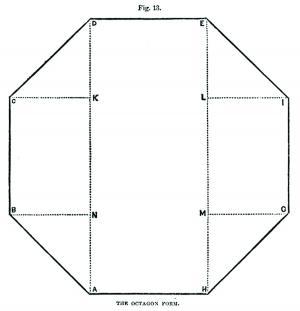

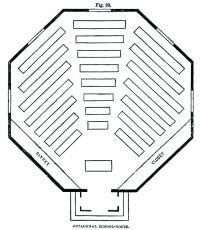

The foundation of Fowler’s argument about octagons is his mathematical calculations that demonstrate how an octagon encloses a greater area than a square form with the same amount of building material for the walls. The octagonal shape also provides better natural light, is easier to heat, and stays cooler in summer. Beyond the economy to be gained in the octagon form, there is also an aesthetic argument against the square. Fowler declares that smooth, spherical forms are more beautiful than angular forms: “Hence a square house is more beautiful than a triangular one, and an octagon or duodecagon than either.” Once one accepts Fowler’s findings from both practical and aesthetic grounds (as if the two were not necessarily one and the same), there is no end to what can be achieved on the octagonal plan. Fowler suggests plans for octagonal schools, churches, and barns in his book.

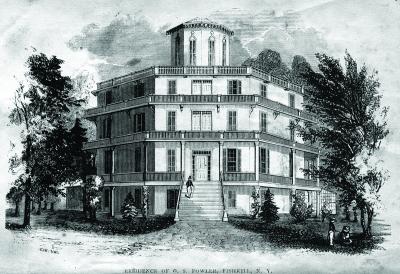

It is a testament to the popular influence of O. S. Fowler and his publishing firm that there was a craze for octagonal construction in the mid-nineteenth century. While many fine examples of octagon houses no longer exist – including Fowler’s own sixty-room home in Fishkill, New York – several examples still survive. Sixty-eight octagon houses are included in the United States National Register of Historic Places, some of which are now open as museums. The Octagon at Amherst College – originally the Woods Cabinet and Lawrence Observatory – was built in 1847-48 and remains an outstanding example of Fowler’s principles.

Michael Kelly has been the Head of the Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College since April 2009. He has curated exhibitions on the Victorian bestseller, Charles Brockden Brown, James Joyce, Emily Dickinson, ornithology, and the history of scientific illustration. He is currently wallowing in the world of nineteenth-century publications about fossils.

Ingres at the Morgan

By ESTHER BELL

From September 9 to November 27, 2011, The Morgan Library & Museum presents seventeen exquisite drawings and some letters by French master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. In this issue, The Common publishes four drawings from the exhibition.

Read an interview between editor Jennifer Acker and curator Esther Bell about these drawings and the artist’s refined sense of place here.

The Net

By DANIEL TOBIN

Translated loosely from a lost Akkadian tablet

discovered among the ruins of Kush.

God of the first waters, Ea, listen,

You who parsed chaos with a net from the day:

Unfasten your knots, let the swells replenish

From subtlest channels, from the seams of flesh.

The galaxies circuit in their bright delay.

The least wind tempts me with what might have been.

The Sting in the Tail

By ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTA

Wearing loose clothes, light cottons,

you sit and fan yourself with a newspaper

supplement, a glass of tepid

fennel-flavoured sherbet by your side.

Death in an Art Deco House

By ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTA

Fortysomething, slight of build,

he lived next door with his parents

in an Art Deco house with garden to match

and tall trees that came up to my third floor flat

from where I could touch their leaves. Squirrels

ran up and down them all day, squeaking.

Parasitical

By DANIEL TOBIN

Despite having no lungs and unable to breathe, the second

head displays signs of independent consciousness….

The first fiction is

I’m talking to you at all,

the more amorphous

of my own Janus head, the god

alive and compassing

what has gone and what

is coming, though

which is which is

hard to say. Did I say

my own? I meant ours, my

sister twin, the comelier