By NASSER AL-DHAFIRI

Translated from the Arabic by NASHWA NASRELDIN

When my friends and I left the homeland, my second departure from Kuwait, there were five of us and ten suitcases. I knew exactly what was in each bag, just as I knew the pain and angst of the five travelers heading toward the unknown. The suitcases were packed with clothes, kitchenware, Indian spices, and various items we didn’t think we’d be able to find abroad. I could only bring four books with me from my vast library back home: Al-Mutannabi, in two parts; the collected works of Mahmoud Darwish; and just one of the volumes of The Unique Necklace. These would constitute the entire library I would survive on, for however long I ended up living in estrangement. Once we’d settled into our accommodation in a small house on Norris Drive in Ottawa, I arranged the books on the sleek wooden flooring, the place being still unfurnished. Then I sat back and simply gazed at them.

Once, when I was a young boy in Kuwait, I had brought home a set of rickety drawers. “What do you want with other people’s rubbish?” my father asked me. Bursting with an excitement that was clearly unreciprocated, I replied: “I’m going to make my own library!” My father just waved his hand at me dismissively and walked away. I took the dilapidated drawers to my room, brimming with joy, and used a hammer and some nails to stop them from wobbling. It wasn’t perfect, given that it was the handiwork of a fourteen-year-old boy, but the joy I felt as I placed the first two books on the top shelf was indescribable, even though they were just books I’d found in a house that had been abandoned by its family. And so, my multifaceted journey of collecting books began. Some of the books were given to me by my teacher, while I borrowed others from various people I knew would never read them. The books that no one bothered to chase me for, I kept.

But there was one time—and God may judge me harshly for this—when I deliberately stole a book from the school library in Kuwait. Although, if confronted, I would always claim it was an accident. It was in my final year of high school. Our headteacher had been so worn down by a group of wild and troublemaking students from our school in Al Jahra that he left them to squander their education and future, rather than rile their parents. One day, they were loitering behind the woodworking shop near the school library. Having lit a fire in a tin of samneh or maybe dates, they sat around the flame, raising their hands toward it like a group of Zoroastrians. Everyone in the overlooking classrooms watched as they stood up and started to kick the tin, which eventually set fire to the wood piled up outside the workshop door. Then the workshop burnt down. While we were all evacuated to the yard outside that separated the library and workshop buildings from the classrooms, the unruly gang were subsequently banished from the school. The fire engines arrived, and instead of just putting out the fire in the workshops, they also drenched the library, not realizing that water is more deadly to books than fire.

After that, the books were in a pitiful state. The school management asked us, as friends of the library, to rescue the ones that were unscathed and separate them from those that had been damaged. But several of the books seemed borderline. While some chose to add these to the “unscathed” pile, I decided to move them to the “damaged” pile instead. Yes, it’s true that I wanted to keep them for myself. When everyone left, I hung back so I could sneak them into a carrier bag and fill up my school rucksack. I was desperate to take them home so I could try and restore them, till they too would end up stacked on the shelves of what I could finally call my own library, however small.

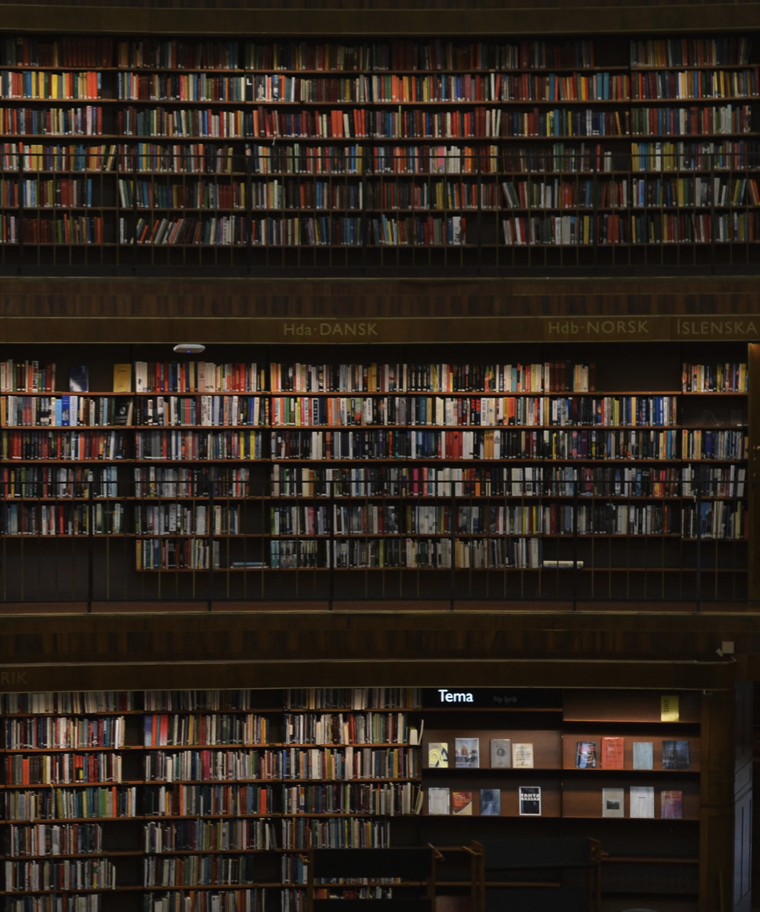

In Ottawa, I had to start my library from scratch once again. My friends and I only stayed in the Norris Drive neighborhood for less than a month before moving to a neighborhood along the Ottawa River. The other four divvied up the first and second floors. I was happy with the basement, which I would share with my new desk, along with the washing machines and all the seasonal items in storage that would be swapped around at the start of summer and winter. I had bought some oak shelves and a small desk, and so the basement gradually transformed into its own world, replacing the unfamiliar one that existed on the outside. The first books I accumulated, to add to the four volumes I’d brought with me, were novels I had found near the blue bins in front of our house, which, for some reason, all had their front covers ripped off. I carried them home, cradled in my arms like some sort of treasure. I didn’t want to share them with anyone. But the prized possession in my brand-new library wasn’t a novel—it was the Gage Canadian Dictionary. My library was beginning to grow, with books I bought from used bookstores that cost a dollar at most, as well as the texts I was studying in my first year of an English literature degree. But without the dictionary, which cost me less than ten Canadian dollars, I would never have been able to decode these books in my basement. Though as a physical space the basement was in reality just two and half meters off the ground, intellectually it was a light-year away.

By the following year, the basement shelves were crammed with used books and the course texts that I refused to sell like other students did. Because I didn’t have much money, I bought second-hand shelves from the Saturday garage sales, which were popular in the summer and which the city was famous for. When it came to books, I had several vices, the first being that I never lent out a book of my own. The other was that I never returned a book I’d borrowed unless its owner asked for it back. The principle I adopted was that if someone didn’t chase me for a book they’d lent me, then they didn’t deserve to own it in the first place. And I assumed that if it didn’t find a second life in my library, it would inevitably end up in a garbage bin, missing its cover.

When I was young, my father would sometimes pop into the room I shared with my brother, where I spent a lot of my free time. He would stop and look at the long shelves that filled every nook and cranny. “They snatch your money and your eyesight,” he huffed. When he finally lost hope that I’d ever give in, he stopped making fun of my library, whose books by now I was amassing from all four corners of the world, and which also included manuscripts my friends would bring back for me from the Arabic bookstores they visited on their travels.

I treated the books I borrowed from the university library with great respect, and I always returned them. But there was one that I just couldn’t resist and which I never returned, pretending that I had lost it: Thus Spoke Zarathustra. I paid the university library double the cost of the title, not because of how rare the copy was, but because it had been signed by the translator, Felix Faris. But, since the dedication was to a person who had nothing to do with Kuwait University’s literature department, I convinced myself that this person didn’t need the book and that the library didn’t deserve it.

The first time I left Kuwait was when the Iraqi forces entered the country and I decided to flee with some of the other university students heading to Saudi Arabia. I was forced to abandon my home library in the hope that we would one day meet again. This time, the only book I packed in my small hand luggage was a poetry collection by Amal Dunqul, because it was the last book I’d brought back with me from a trip to Cairo that year. My family stayed in our modest house, until the air strikes began. After that, they moved in with some of our relatives closer to the heart of the city, a safer location than that of our home, which was surrounded on three sides by military camps and ammunitions stores, and the sea on the other. As they rushed around packing up their things, my father strode past my library, before quickly turning back to it. “I won’t leave his library,” he announced, stoically. “I’ll stay. You can all leave.” My brother, who relayed this story to me, did everything in his power to change his mind, but my father refused to budge. When my father said “No” to something, he only had to say it once and his decision wouldn’t be open to discussion. We could wear ourselves out trying, but he wouldn’t waver. My brother pleaded with him, urging him to go on ahead with the rest of the family, promising him that he would stay with the books instead. It was only after my brother gave him his word that he wouldn’t abandon the library unless the war ended that my father finally relented.

I did make it back to my home library that time, and my father was very proud that my books were perfectly intact, just as I’d left them. This was the clearest statement of approval from my father, who seemed to object to the library whenever I was around, but then treated it tenderly as soon as my back was turned. On my return from Riyadh, I brought back a copy of Kane and Abel by Jeffrey Archer, which I’d found at a second-hand book market, to add to my collection. It was a book that I had read during my ten months abroad and then translated, to help overcome my loneliness. During my time there, I also picked up a selection of books by Saudi literary writers, most of them dedicated to me by the authors themselves.

By the time I completed my postgraduate studies in Ottawa, my new library consisted of an entire wall of bookshelves, as well as several large boxes piled up on the floor and filled with numerous articles I had photocopied over the six years. But my relationship with the foreign language I was now immersed in could never compare with my relationship with the Arabic language I had left behind in Kuwait—that much was obvious. I didn’t really engage with my new library, even though I had started to stock it with some Arabic books, in an attempt to regain the sense of excitement and attachment I felt toward it in the early days. My yearning for my original, vast library was still integral to the nostalgia I felt toward the homeland.

I had left. My father was no longer there. I asked my siblings to look after my library and not to lend out any of the books. To my relief, my sister offered to keep it at her house. For four years, I remained in constant exile, but in my fifth year, I dared to travel back to Kuwait. My sister and her husband were moving abroad for work and were planning to rent their home out to one of the Salafist fronts involved in charity work and various other activities. It was a five-year rental contract, which meant that there were two possible options facing my library: it would have to be either removed from her house again or else hidden away somewhere inside. My sister chose the second option. She piled up the boxes of books horizontally along the interior wall of the ground-floor living room, then asked the builders to build a wall parallel to the original. That would then form the new separating wall, so that no one would suspect that there was another partition behind it.

On one of my later visits, I stood in front of the house, which was now busy as a beehive, with people streaming in and out with long, bushy beards, dressed in short jalabiyas, and glaring at me like I was one of the infidels of Quraish as they strode around chewing miswak. I couldn’t imagine how Marx, Guevara, Darwin, Omar Khayyam, and Taha Hussein could have ever existed behind those walls.

Five long years had passed, and I never did meet any of the books from my original library again. I only have the four volumes I rescued when I first left for Ottawa, and an old photo of the library, which I found in a photo album. I hung up the photo in the new library, so I could reminisce over it at my leisure.

I’ll return soon to embrace those names that taught me so much. I will return, so long as the new wall doesn’t collapse onto the old one.

Ottawa, 2016

Nasser al-Dhafiri born in 1960 in the Kuwaiti city of Al Jahra, was a member of the Bedoon (stateless) community in Kuwait. At the time, the Bedoon were not permitted access to a university education, so, upon graduating from school in 1979, al-Dhafiri joined the Ministry of Defense as a soldier. In 1982, when the members of the Bedoon community were allowed to enroll in Kuwait University, he left his job, joined the civil engineering program, and published his first short stories in that same year. In addition to writing poetry, stories, and novels, al-Dhafiri worked in journalism. He published eight books, most of which feature the stateless community and their suffering. A number of these books were subsequently banned by Kuwaiti censors. In 2001, he immigrated to Canada, following the Kuwaiti government’s restrictions on the Bedoon during the 1990s. He completed his postgraduate studies there and acquired Canadian nationality. Al-Dhafiri died in Canada in 2019 after a battle with cancer and is buried in the city of Ottawa.

Nashwa Nasreldin is a writer, an editor, and a translator of Arabic literature. Her translations include the collaborative novel Shatila Stories and a co-translation of Samar Yazbek’s memoir, The Crossing: My Journey to the Shattered Heart of Syria. She is the managing editor of ArabLit.org, a website showcasing Arabic literary translation.