Skylight Books

Thursday, January 25, 7pm

1818 North Vermont Ave., Los Angeles, CA

Free and open to the public

With so many California contributors to our Issue 26 farmworker portfolio, we had to have a West Coast celebration! Join The Common for a celebration of writing and art from the seasonal, migrant, and immigrant farmworkers who power California’s vast food and agriculture systems.

Come celebrate with us at LA’s renowned Skylight Books for a reading and conversation about place, immigration, writing, justice, farmwork, and family with contributors from California. All are part of our portfolio of writing and art from twenty-seven contributors with family roots in farmwork. It was co-edited by Miguel M. Morales.

Essayist Amanda Mei Kim writes about the ways that collective power, racism, and nature weave through the lives of rural Californians of color, through the lens of her experience growing up on her family’s tenant farm just outside LA.

Poets Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, Aideed Medina, and Oswaldo Vargas write about the struggle and the beauty of work in the fields and on farms. Their work highlights the nuance and diversity of that experience—queer discovery, activism and protest, shared labor and community.

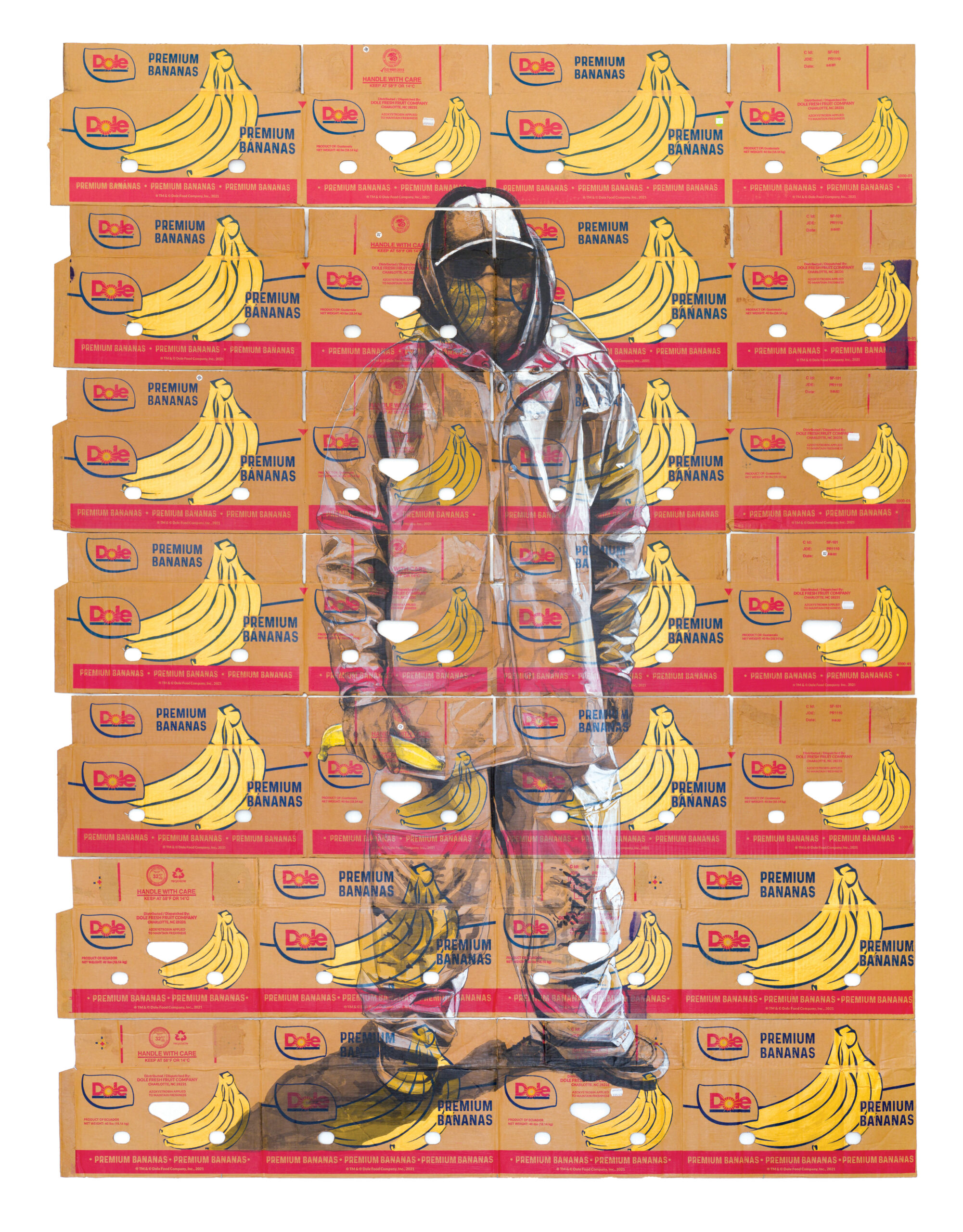

Artist Narsiso Martinez creates moving portraits and scenes of farmworkers in the fields, painted on flattened cardboard produce boxes discarded from grocery stores. This work is drawn from the nine seasons he worked in the fields of Eastern Washington state, to fund his undergraduate and graduate studies. Narsiso writes, “When I nest images of farmworkers amidst the colorful brand names and illustrations of agricultural corporations, I hope to help the viewer make a connection, or a disconnection rather, and start creating consciousness about the people that farm their food.”

The event will include brief readings by each writer, a short presentation of Narsiso’s artwork, and then a moderated conversation and Q&A. It will be hosted by the magazine’s managing editor Emily Everett. Wine and drinks available!

Allison Adelle Hedge Coke came of age working in fields, factories, and waters. A labor and environmental poet, Hedge Coke was a sharecropper by the time she was mid-teens and continued manual labor until nearing thirty years of age, when disabilities precluded continuation. Following former fieldworker retraining in Santa Paula and Ventura, California, in the mid-1980s, she began teaching and is now Distinguished Professor and Mellon Dean’s Professor at UC Riverside. She is the author/editor of eighteen books, including Look at This Blue (National Book Award finalist), Burn, Streaming, Blood Run, Off-Season City Pipe, Dog Road Woman, The Year of the Rat, Effigies I, II, & III, Ahani, and Sing.

Narsiso Martinez (b. 1977, Oaxaca, Mexico) came to the United States when he was 20 years old. He attended Evans Community Adult School and completed high school in 2006 at the age of 29. He earned an Associate of Arts degree from Los Angeles City College, and a BFA and MFA from California State University Long Beach, where he was awarded the prestigious Dedalus Foundation MFA Fellowship in Painting and Sculpture. Drawn from his own experience as a farmworker, Martinez’s work focuses on the people performing the labors necessary to fill produce sections and restaurant kitchens around the country. His portraits of farmworkers are painted, drawn, and expressed in sculpture on discarded produce boxes collected from grocery stores. His work has been exhibited both locally and internationally. His work is in the collections of the Hammer Museum, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, MOLAA, University of Arizona Museum of Art, Long Beach Museum of Art, Crocker Art Museum, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Martinez was awarded the Frieze Impact Award in 2023. Martinez lives and works in Long Beach, CA.

Aideed Medina is a Pushcart Prize-nominated poet, spoken word artist, and playwright, and daughter of Miguel and Lupita Medina of Salinas, California, and the United Farm Workers movement. She is the author of 31 Hummingbird and a forthcoming full-length poetry collection, Segmented Bodies, from Prickly Pear Press.

Amanda Mei Kim writes about the ways that collective power, racism, and nature weave through the lives of rural Californians of color. Her writing has appeared in The Common, The New York Times, PANK, LitHub, Brick, Tayo, Eastwind Magazine, DiscoverNikkei, and Nonwhite and Woman. Poems are forthcoming in an anthology from Haymarket Press. She is a member of this year’s Changemaker Authors Cohort and a de Groot Writer of Note. She is a former Steinbeck Fellow and California Arts Council Fellow. Amanda is the founder and lead researcher for Kanshahistory.org, which publishes the property transfer records of Japanese Americans who had their farms taken during World War II. Her professional work focuses on agriculture, equity, and ethnic media. She is also a creative strategist for Hmong American farmers who are being persecuted by their local government. Amanda is writing a memoir-in-essays that uses her family’s 125-year history as agricultural workers to show how people of color created a more just and sustainable food system. More at www.amandameikim.com.

Oswaldo Vargas is a 2021 Undocupoets Fellowship recipient. He has been anthologized in Nepantla: An Anthology Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color and published in Narrative Magazine and Academy of American Poets’ “Poem-A-Day,” among other publications. He lives and dreams in Sacramento, California, for now.